One of my earliest exposures to political analysis stemmed from my being an avid reader, when small, of Richmal Crompton’s many books about a ceaselessly rumbustious schoolboy named William.

In one of those books – dozens of which were published in the decades immediately before and after World War Two – William and his mates are contemplating the various candidates standing in an imminent election.

All such candidates, says William’s pal Ginger, “want to make things better, but they want to make ’em better in different ways”.

Conservatives, Ginger goes on, “want to make things better by keepin’ ’em jus’ like what they are now”. Liberals “want to make things better by alterin’ them jus’ a bit, but not so’s anyone’d notice”.

Socialists, by which Ginger means the Labour Party, “want to make things better by takin’ everyone’s money off ’em”. And Communists “want to make things better by killin’ everyone but themselves”.

The Conservative worldview took shape in the 1790s

The story featuring this juvenile venture into political punditry first appeared in 1929. It’s unlikely, I guess, to have attracted a formal response from any of the four parties whose competing programmes for government Ginger boiled down to a sentence apiece.

But, had reactions been sought from Communists, Socialists and Liberals, those reactions – given Ginger’s scathing summaries of their policies – are unlikely to have been favourable.

Conservatives, on the other hand, could well have responded more positively. While they might have taken some mild exception to the suggestion that the Tory road to betterment involved keeping everything exactly as it was, they would certainly have agreed with Ginger that, in contrast to Communists, Socialists and even Liberals, Conservatives were unshakeably opposed to anything smacking of far-reaching change.

So it had been, since a distinctively Conservative worldview had begun to take shape in the 1790s – a decade that brought revolution to France and widespread calls for something similar in Britain.

Conservatives once aimed to conserve

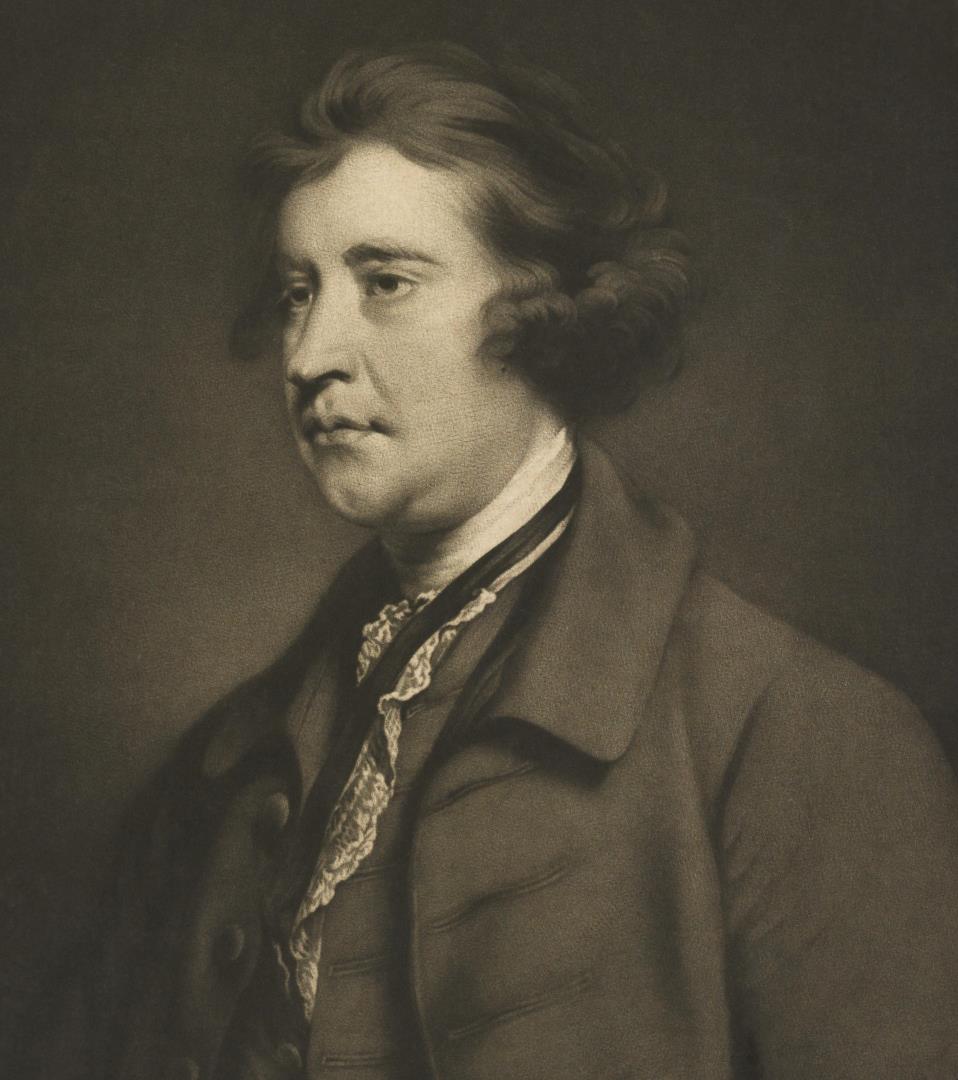

It was all very well to overturn the old order in the name of liberty and equality, argued writer and politician Edmund Burke – long seen as Conservatism’s founding father. But, once this process started, it was all too liable to get quickly out of hand.

This party’s overriding mission was to keep established structures firmly in place

That, Burke and others pointed out, was exactly what had happened in France. Moderate reformers had been elbowed out of the way by more radical elements who’d ended by guillotining everyone, including the king and queen, thought to stand in their way.

Subsequent revolutions, not least the one that broke out in Russia in 1917, served only to enhance the appeal of Burke-style thinking to what had become, by that stage, a highly organised Conservative Party.

This party’s overriding mission was to keep established structures firmly in place. Conservatives aimed, as their party’s name suggested, to conserve. Monarchy, the church, the rule of law, the landowning and farming classes. All these and much more besides were to be safeguarded and protected.

Thatcher era brought revolutionary change

When radical reforms such as tax-funded old age pensions or wholesale nationalisation were forced through – by Liberal governments in the first instance, by Labour administrations a bit later – these reforms met, predictably, with Conservative opposition. When Tories returned to power, however, reform was seldom reversed – in part, perhaps, because reversal could itself prove dangerously disruptive.

Some people prospered. Others didn’t. Inequality increased

So, matters continued until, in the 1980s, the Conservative Party of Margaret Thatcher and her successors became itself imbued – in ways old-school Tories hated – with an almost revolutionary zeal for change.

State-owned industries – electricity, gas, water, the railways – went into private hands. Council house construction was stopped and existing council houses sold off cheaply. Mines and factories were closed. Regulation of business and finance was drastically cut back.

Some people prospered. Others didn’t. Inequality increased.

Today’s Brexiteer-controlled Conservative Party has ceased to be ‘conservative’

Upheaval ceased during the 1997 to 2010 Labour interlude. But, since then, it’s become still more frenzied. What was once seen as a key Tory achievement – Britain’s membership of the European Union – has been overturned by a hard-line Brexit, accompanied by a growing disregard for international law and much else seen in former times as sacrosanct.

The Conservative Party of Boris Johnson – whose casual relationship with truth, convention and probity marks him out as a man to whom earlier Tory grandees wouldn’t have given the time of day – is a party with zero tolerance for Conservatives of the sort who might prefer “to make things better”, as William’s pal Ginger put it, “by keepin’ ’em jus’ like what they are”.

Whatever else today’s Brexiteer-controlled Conservative Party may have become, it has certainly ceased to be, in the longstanding sense of that term, conservative.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands