The irony isn’t lost on me that I finally started watching The Sopranos while trying to distract myself from rapidly intensifying anxiety.

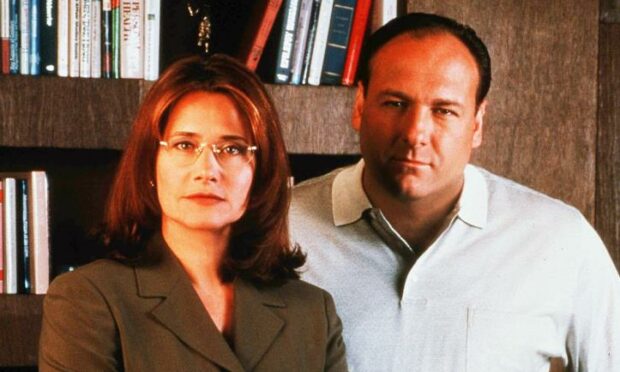

If you haven’t seen it, the hit TV series opens with main character and mafia boss Anthony Soprano experiencing a frightening panic attack. He tries desperately to link his fainting spells to a physical illness, before eventually considering that his mental health may need attention.

Like Tony, it took me a while to properly join the dots between my anxiety and its sometimes extreme physical manifestations.

In my early twenties, I started to experience an onslaught of digestive issues – tummy aches, loss of appetite, nausea. I took over-the-counter IBS medication and did more exercise. I stopped drinking coffee entirely. I began eating a vegetarian diet, and then went vegan for a while. None of it helped.

Over time, it started to dawn on me that the root cause probably wasn’t physical. A quick Google search will tell you that nausea and stomach pain are some of the most common anxiety symptoms.

Sometimes there were obvious triggers – a looming deadline or a stressful day at work – and sometimes there weren’t. Still, becoming conscious of how my mental health could affect my body made the discomfort a bit easier to deal with.

The pandemic battered our mental health

It’s no shock that feelings of anxiety and depression rocketed for many people amid the fear and disruption that reigned in 2020 and 2021. The unoriginal yet increasingly important question is, what is the long-term human impact of operating in crisis mode for so long?

The available data suggests we haven’t bounced back, psychologically-speaking. And, personally – after starting to feel like I’d vanquished that particular demon just a few years ago – I’ve noticed my old frenemy anxiety creeping up on me more and more often since the pandemic began.

It’s been drilled into us that we should talk about our mental health and share the burden if we’re feeling overwhelmed. But our friends and family members aren’t, for the most part, experts

It’s the reason I found myself sitting on the sofa on an otherwise unremarkable evening, breathing deeply and trying my hardest to focus on The Sopranos instead of my pounding heart and churning stomach.

I attempted to type out messages to friends that accurately conveyed how I was feeling without coming across as overdramatic, attention-seeking or – for want of a better word – crazy. I didn’t end up sending any of them.

Routine mental health care is nowhere near what it should be

It’s been drilled into us that we should talk about our mental health and share the burden if we’re feeling overwhelmed. But our friends and family members aren’t, for the most part, experts in that field. They won’t always know the right thing to say. They might be having their own extremely bad day.

In The Sopranos, Tony doesn’t open up to his gangster pals. He goes to see a shrink – a psychiatrist.

A few years ago, I tried cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). It helped a lot when it came to identifying and coping with my physical anxiety symptoms. It also cost me £70 per session.

If I had requested counselling through the NHS back then, I know there would have been a waiting list. Now that the pandemic backlog has slowed most health services to a virtual standstill, waiting lists are even longer.

Mental health crises should automatically be treated as the emergencies they are, but it should also be acknowledged that properly treating anxiety, depression and other issues is a long game.

It shouldn’t feel easier to do nothing rather than ask for help

Scotland and the wider UK’s current approach to routine mental health care is nowhere near what it needs to be. People are suffering and lives are being lost unnecessarily as a result. This isn’t a new complaint but it bears repeating over and over until it is resolved.

Given that performing everyday tasks can feel insurmountable from the depths of a period of poor mental health, the process of seeking appropriate assistance should be simple and calm. It shouldn’t feel easier to do nothing rather than ask for help.

We’re running out of time

During the summer between high school and university, I started to feel sick; unrelenting nausea, sometimes all day, always every day. A doctor prescribed me pills to reduce the amount of acid in my stomach and sent me on my way.

I was 17 and standing on the precipice of the biggest and most daunting life change I’d ever faced. It’s so clear to me now that I wasn’t just nauseous, I was anxious. Yet, hastily scribbling out that prescription, my GP didn’t pause for a moment to ask what was going on behind the scenes.

Maybe it wouldn’t have made a difference. But, if I had learned more about anxiety then – even tried CBT a decade earlier than I eventually did – maybe I would have been spared a lot of heartache. And some stomach aches, too.

Now that the grim numbness of lockdown has well and truly worn off, I’m worried about the people left dealing with the psychological fallout of Covid-19. Those people who never had sore tummies before but are suddenly plagued by them. The ones mainlining Rennies for acid reflux that won’t go away. The ones who find they can’t bring themselves to get out of bed, no matter how hard they try.

I’m worried that, like me, it could take them close to a decade to figure out what’s going on between their bodies and their minds. I’m worried that some of them might not be able to hang on that long.

It shouldn’t take money or winning the waiting list lottery to get them the help they need.

- If you are struggling with your mental health right now, you can contact Breathing Space or the Samaritans for free

Alex Watson is the Head of Comment for The Press & Journal and hasn’t finished The Sopranos yet – no spoilers, please