When teaching creative writing, I often ask participants to find what I call “the kernel of truth” – an authentic detail that springs from experience rather than imagination.

So often, it’s that small, incidental detail that, as a reader, breaks your heart.

In reports of the case of Stephen McManus, found on the roof of Charing Cross hospital in London, that detail was the fact that he was wearing slippers. A symbol of safety and comfort and home.

But this pensioner died alone, in his slippers, on a winter’s night, on a hospital roof.

Stephen McManus was a type 1 diabetic, suffering a hypoglycaemic episode. His blood sugar levels had fallen to dangerous levels and he was, apparently, in a confused state, with slurred speech and erratic behaviour.

Yet, a junior doctor discharged him.

He was escorted out by security guards, without a phone, or money – or, indeed, shoes – and without his family being informed.

In his confusion, he re-entered the building, ending up on the roof. He was found dead the next morning.

There is something wrong with a society that has no compassion for human error, that invariably seeks to vilify when things go wrong.

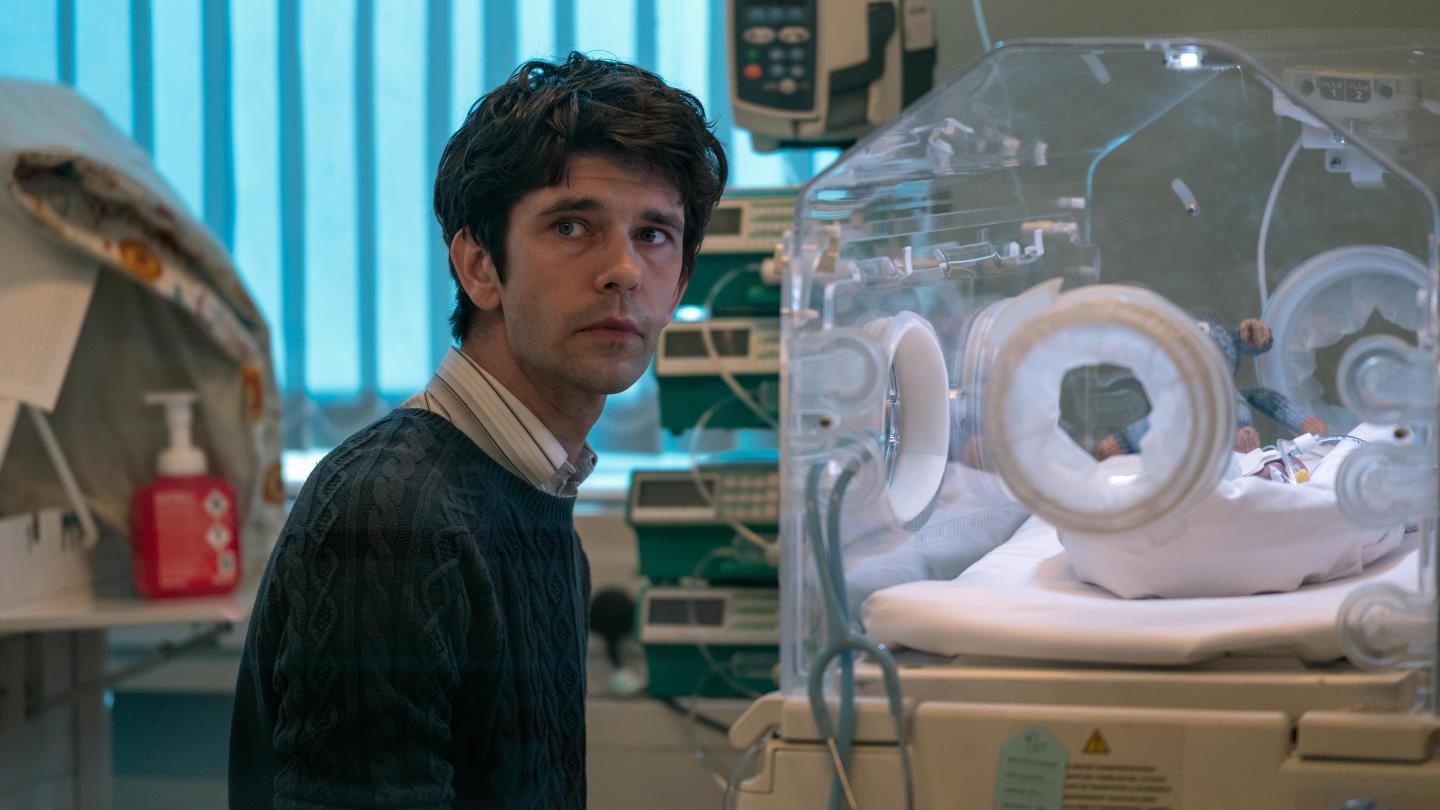

We can see in the BBC’s controversial new drama series, This Is Going To Hurt, written by ex-doctor Adam Kay, the traumatising effects of medical mishaps on overworked doctors.

Based on his bestselling memoir, the series shows Kay suffering debilitating guilt and flashbacks after making a wrong call.

But, when error is an indication not just of a one-off failing, but a systemic problem, questions need to be asked.

The answers are easy enough to guess. Long hours, high stress, low staffing levels, insufficient – and wrongly prioritised – resources. But there’s more than that.

Our NHS has become a lumbering beast

In an age where we talk of angels and heroes in the health service, it is considered at best ungrateful and at worst sacrilegious to criticise NHS culture.

Yet, in a 2020 societal attitudes survey, only 53% of people in Britain were “very” or even “quite” satisfied with the NHS.

The NHS was a wonderful political initiative that recognised there were certain things that were your right, not because you had money, but because you were human.”

Why? Because the health service has become a lumbering beast – top-heavy, inefficient, and hierarchical.

It is, at times, a disrespectful and overly-controlling organisation, that feels as if it is being run for the convenience of staff rather than patients, operating like some grace and favour charity where the toffs dish out limited aid to the great unwashed.

Stand in line. Take what you’re given. Question at your peril.

In a 1948 government leaflet launching the NHS, there was a very important, but often now forgotten, recognition. The NHS, it said “is not a charity. You are all paying for it, mainly as taxpayers”.

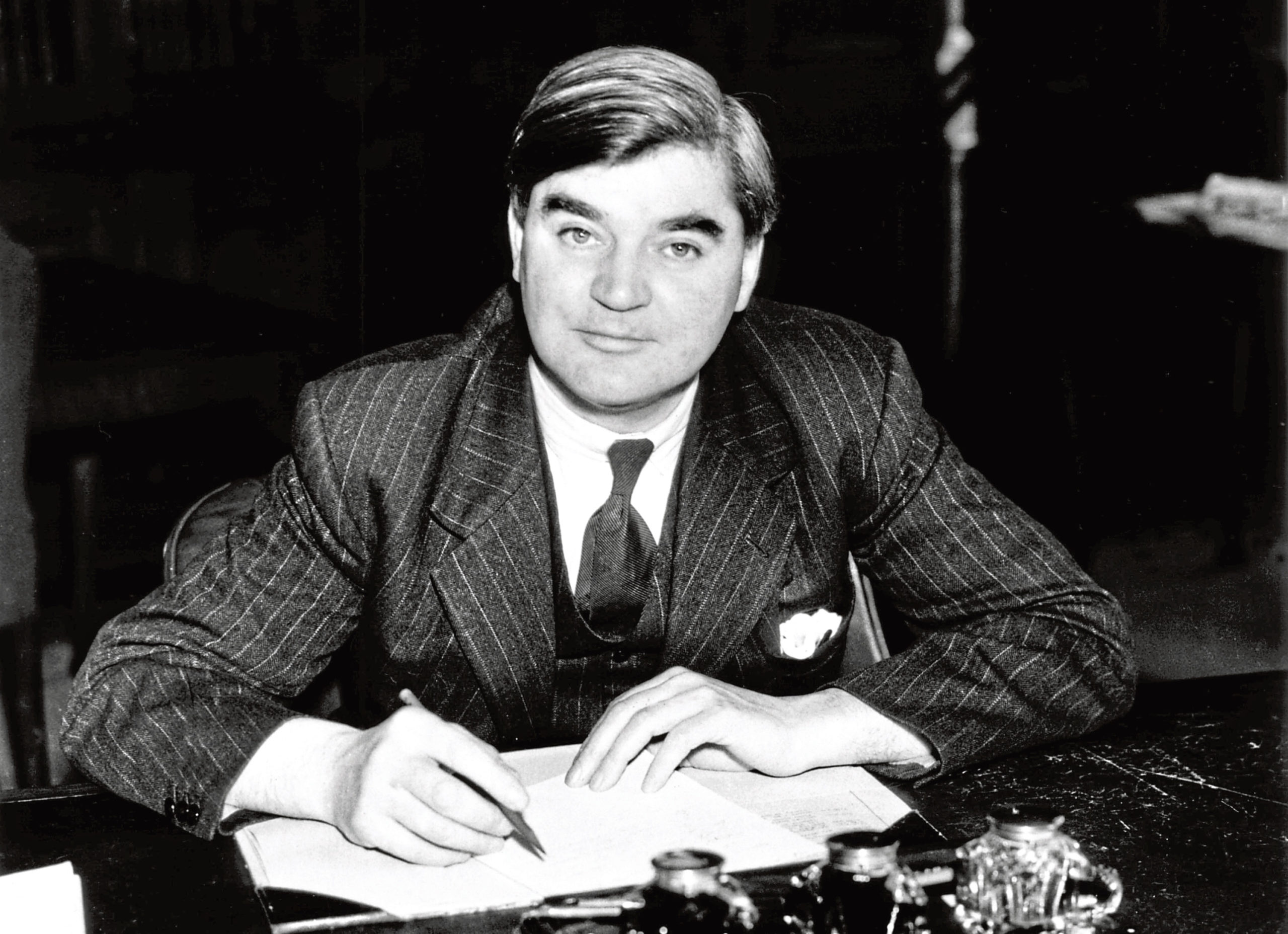

It was a wonderful political initiative, instigated by Labour health minister Aneurin Bevan, that recognised there were certain things that were your right, not because you had money, but because you were human.

Health. Education. Justice under the law. It recognised the dignity of all.

Isn’t it better to acknowledge it than pretend?

The starkness of This Is Going To Hurt has been criticised, particularly by the Positive Birth Movement.

Set in a labour ward, it shows “a paternalistic and misogynistic attitude” to female patients who are shown as “thick cows […] vaginas or slabs of meat”.

Maybe it does. But, having been in a maternity ward, that’s not entirely fiction.

The criticism misses the point. The series does not present what the health service should be, but what it actually is, with all its mistakes and cover-ups; its arrogant consultants; its under-funding and relentless sea of patients and problems.

But, also, its brilliance.

The script is cleverly funny yet darkly brutal. Kay – who despite a sardonic, cynical exterior is essentially a committed, caring doctor – has not just captured a kernel of truth in his fiction. He’s identified a great big cultural reality.

Isn’t it better to acknowledge it than pretend?

Time to revert back to founding principles

Stephen McManus’s son, Jonathan, like many of us, expressed both affection for the NHS and frustration, saying his father’s discharge was “inexplicable”.

It was – but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t demand explanation.

It’s time the NHS became more responsive, compassionate, and truly person-centred.”

As we have seen recently in policing, huge public organisations can develop toxic cultures.

So, the questions we ask, the explanations we require, are not to destroy the career or confidence of a junior doctor, but to examine a systemic problem that’s far bigger than they are. Unless you face, you can’t fix.

There are wonderful practitioners in the NHS who deserve our gratitude. But Stephen McManus is just another reminder that it’s time the NHS became more responsive, compassionate, and truly person-centred.

Time, in other words, to revert to founding principles and make the NHS everything it can be.

And time for the suits who run it to remember exactly in whose ownership it lies.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter.