Covid has come late to our family.

Having avoided it entirely at its height, we suddenly have two spluttering, coughing cases in the house, ages 20 and 12. Cue UN-style domestic sanctions and confinement.

It serves, if it were needed, as a small personal reminder of just how out of control, how subject to external, random intervention, our lives have become over the past few years. The settled will of the West, the sense that history had found its safe, happy medium and that what remained to be fought over was the relatively small stuff, has been exploded. If we thought our task was simply to better order our affairs, that fate would largely leave us to our own devices, then no longer.

First Covid, now Ukraine. It has been decades since the world has felt so dangerous, so poisoned and teetering on the edge of the void. Vladimir Putin’s catastrophic war has shocked us to our spines. It is a thing from the history books: violent, unhinged war in Europe, rape, pillage and slaughter, a looming nuclear stand-off. A nuclear stand-off, for God’s sake.

There is no sense of control or happy mediums, now – only known unknowns and, most likely, unknown unknowns. We do not know how to stop this conflict. We do not know what Putin’s or our limits are, or will be in time.

A lot of questions and no real answers

We desperately want to help the Ukrainians, but how? A no-fly zone, to buy them space and time? We are told that would set in train a third world war. A Chinese-negotiated peace, given their influence over Putin? China has little interest in playing that role, the experts tell us.

We desperately want to protect the vital life force that is Vlodomyr Zelensky, but wait anxiously for the terrible possibility of his assassination. We would provide a home for refugees, many of us in our own houses if necessary, but Home Secretary Priti Patel – as if to remind us of how wretched this government can be – seems reluctant to open the doors.

Will the sanctions work? I read that the multibillionaire Putin and his allies are well-feathered enough to flaunt their way through. I read that it is ordinary Russians who will suffer – the Russians who have little say over who governs them; the Russians who have so bravely taken to the streets to protest this war, facing up to a dictatorship that, in turn, deploys a brutal security structure.

I’ve read contesting arguments on all sides of all these questions, as I suspect you have. There is no reassurance to be found

Does Putin care about the mass immiseration of his people, or will ego and a warped sense of destiny lead him to carry on regardless? Will the Russian despot be deposed by those around him, even bumped off, or will the loyalty of the thugs and the hyper-enriched around him keep him safe? And what the hell happens if Trump gets back in?

I’ve read contesting arguments on all sides of all these questions, as I suspect you have. There is no reassurance to be found.

The great comfort of our time, of baked-in geopolitical stability and security – again, it’s all relative – has suddenly been whipped away, exposed as little more than a beguiling glamour. We are as vulnerable to the world’s whims, its toxins and its maniacs, as previous generations. The villains have slipped through the gates and hold a dagger to our throats.

‘Here we are, feeling something’

We are being taught lessons that batter and wound us. We have lived for so long in a climate of online outrage and venom, maintained at a pitch that its subjects rarely merit. Our politicians have waged rhetorical war on each other over the finer points of policy, minnows swaggering like giants but still splashing around in a shallow pool.

As the great American columnist Peggy Noonan put it last week: “Most of the forces of modern life tend towards the synthetic, the presentational – virtual feelings and enactments. And yet here we are, feeling something.”

Here we are, feeling something. The rawness is unbearable, as is the helplessness. There is no button that can be pushed or form that can be filled in, no petition that can be signed or cleverly-worded tweet that can be sent, that will make a whit of difference.

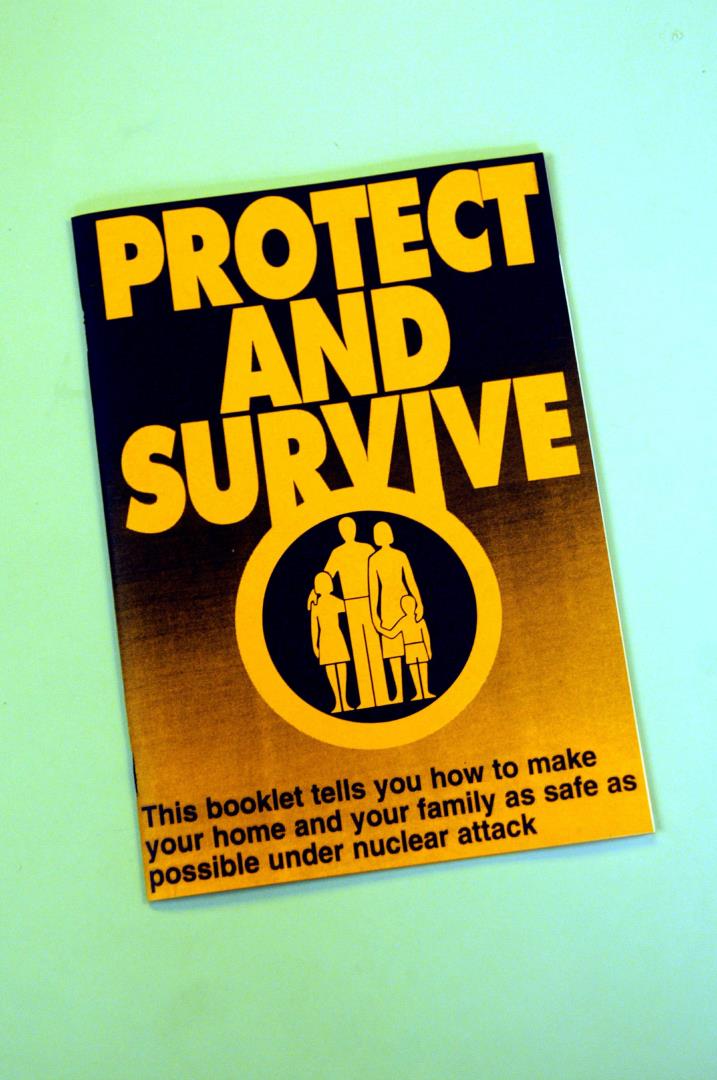

For those old enough to remember the Cuban Missile Crisis, the echoes of history must resound. For those of us who lived out the final years of the Cold War, who spent our childhood amid the lingering prospect of nuclear annihilation, there is sudden, tremulous recall.

A vast global reordering is underway, of alliances and economies and militaries and, finally, emotions. We might yet be saved, but it would do us well to accept that we will never be safe.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland