When I was young I had a Polish great uncle, Wasyl Lewicki.

Wasyl died when I was perhaps five or six, maybe younger. I have no recollection of going to a funeral and my memories of him are quite scattershot.

I remember Wasyl as a tall, friendly man. He and my Auntie Jeannie lived in Whitehills, in a large, old, white, harled house between the Low Shore and Downies fish market, where Wasyl at one point worked.

To my brother and I, much of the house was off limits. When we visited, we would often sit in the kitchen. I remember a large Aga, my Aunt Jeannie smoking at the kitchen table and Wasyl painting gnomes, which he made and fired from clay and sold in the town. These little, blue, red and green mannies, with hats.

He kept lovebirds, which I think were called Pinky and Perky. They made a racket. He fixed shoes. He fixed fishermen’s oilskins. He went to sea for a time. I also remember him gardening the grounds at the local church.

Apparently I could count to 10 in Polish – jeden, dwa, trzy… and so on – almost as quickly as I could in English. My Polish partner probably wishes I had remained that bilingual into adulthood. Dwa piwa, proszę.

Ukraine has been on my mind

I’ve given Wasyl a lot of thought recently. Although Polish, Wasyl was brought up in Lwow, now Lviv, in Ukraine. At the time, it was part of the Second Polish Republic but, after World War Two, it became part of the Soviet Union.

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, part of newly independent Ukraine. It has become a focal point in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as new refugees from other cities pass through while travelling west.

Wasyl, at what we think was rather a young age, maybe only 16, left Lwow to join the Polish Army, as WWII began, with the German and Soviet armies beginning to encroach on southern Poland.

He was eventually posted to the UK and found his way to Duff House, Banff, where he guarded German prisoners of war. He was there, apparently, when it was bombed. Soon after, he was married to my great aunt.

He left behind family in Poland, some of whom stayed in contact with Jeannie. One letter came to us from a great-grandniece of his. “Dear Relatives,” it started. Some of the writing was in Cyrillic, but we worked out it was from a town called Chervonohrad in Ukraine, north of Lviv.

It has been heart-wrenching to watch the news over the past week and witness the destruction that has been unleashed on Ukraine

As such, Ukraine was somewhere I had always had on the list. Lviv in particular, but also Kiev and Odessa.

It has been heart-wrenching to watch the news over the past week and witness the destruction that has been unleashed on the country. Only three weeks ago, conflict had been confined to the east.

It’s easy to feel small and powerless

I had what one might call “a moment” on Newburgh beach last Sunday, where I was supposed to be relaxing. I had just read Vladimir Putin’s statement that he was putting his nuclear deterrence forces in a state of “high alert” in response to Western economic sanctions, four days after he had launched his full-scale invasion.

“Consequences they have never seen” was the threat. Unfortunately, they are all too easy to imagine.

So, among the spray and the seals and the sand, brushed and blown by the high wind, I felt very small and insignificant. I felt scared to look at any social media for the next few hours, lest I read anything worse.

I thought about the people in Ukraine who had had their lives completely upended in what felt like the blink of an eye. I wondered if my far flung “relatives” were still there somewhere. What they might be doing.

Since then, we’ve had a steady stream of worsening news emerge from Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kherson and Mariupol in particular. Cities whose names will carry the memory of this war for a long time to come, even if it’s over relatively soon. Cities which can be imagined by people in Scotland to be familiar.

We’ve been to Prague and Krakow, Budapest and Berlin. Can they be so different? Trains and blocks of flats, old towns and TV towers.

The UK must do better

The biggest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII has begun. An estimated 1.5 million people have been displaced already. Overwhelmingly to Poland, but to Romania, Slovakia, Hungary and Moldova, too.

As I write, the UK Government has issued 300 visas to Ukrainians fleeing the war. They need our help. We must do better.

Lviv has received 200,000 internally displaced people already, the same amount Boris Johnson believes the UK can handle in total. Fifty thousand pass through Lviv every day, heading west.

The Mayor of Lviv has stated that the city is at the limits of its ability to help refugees, due to the sheer numbers they are seeing. Last week, his advice to Johnson was to seize Russian oligarchs’ mansions in London to aid the humanitarian crisis.

My uncle Wasyl never returned home to Poland, for one reason or another, making his life and home in Whitehills, a village not short of Polish descended folk. Lwow became Lviv.

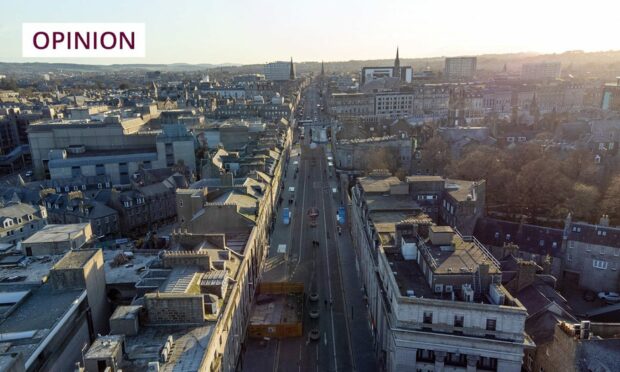

This week, Marischal College was illuminated, yellow and blue in support of Ukraine. I hope that Ukrainians travelling now, passing through landscapes Wasyl may have known as a boy, will one day get to return to theirs.

Until then, I hope we can help as many as possible.

Colin Farquhar is head of cinema operations for Belmont Filmhouse in Aberdeen