What to do with the empty building that once housed Aberdeen’s John Lewis store?

Perhaps, or so it’s been suggested by city councillors, it could become a northern outpost of London’s Natural History Museum.

Given the uplift that Dundee’s got from providing a base for just that sort of offshoot – the Victoria and Albert Museum in that case – the attractions of some such initiative are clear.

But, might there be a case for a more homegrown, more locally rooted, alternative – a museum that, by celebrating what’s been achieved over the years in Aberdeen and in its rural hinterland, looks to enhance the confidence of a city and a region that, as oil-related industry withdraws, could arguably do with a boost?

And there’s a lot worth celebrating.

A city with so much to celebrate

This is a city that, centuries ago, developed its own highly successful trading links with Scandinavia and the Baltic.

A city that reconstructed itself by creating a central thoroughfare, Union Street, in such a way as to span the Den Burn gorge that had barred the original burgh’s expansion to the west.

A city that engineered its own industrial revolution in the shape of the paper and textile mills that clustered around the River Don’s lower reaches.

A city whose shipyards built tea clippers like Thermopylae and Cutty Sark; ships that were the fastest ever cargo vessels prior to the age of steam; ships that, when under sail, were also things of beauty.

A city with a trawler fleet capable of fishing as far away as the Arctic.

A city that, for long enough, had as many universities – King’s and Marischal Colleges – as all of England.

A city that, for all its growing urbanisation, remained in many ways a country town.

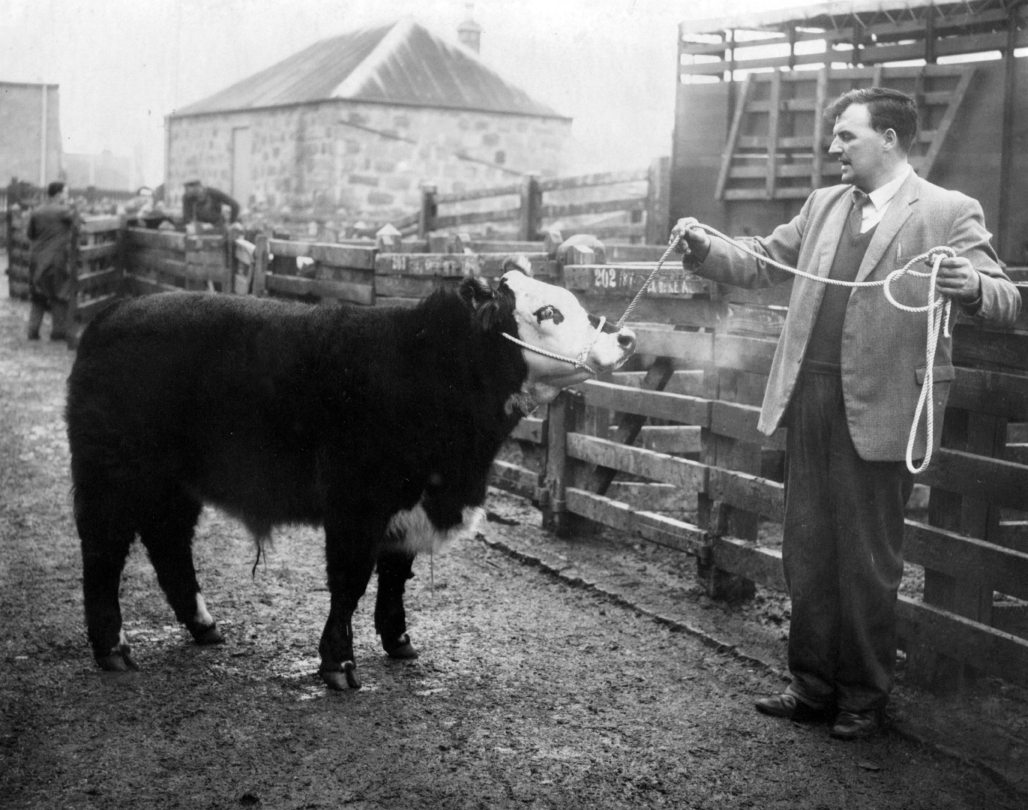

Which is why, until well into the 20th century, sheep and cattle were herded and transported through Aberdeen streets when en route for the massive livestock mart at Kittybrewster.

And why so much of Aberdeen’s Victorian and subsequent prosperity derived from its provision of the banking, legal and other services required by the Aberdeenshire farmers who turned what had long been a far from fertile countryside into one of the most agriculturally productive parts of Scotland. Their accomplishments, too, are worthy of some celebration.

As are the lives of people who, though they seldom qualify for much in the way of commemoration, were key to Aberdeen’s growth.

A way to restore a sense of mission and unity

An awful lot of what’s called “heritage” consists of the stately homes and castles of the rich and powerful. Which is why, south of the border, Historic England has just launched an Everyday Heritage Grants scheme with a view to “celebrating working class histories”.

Aberdeen won’t qualify for English Heritage cash. But that’s no reason for not undertaking a venture of the same sort.

And, where better to accommodate such a project than a building that, before John Lewis took it over, was Norco House – the premier outlet for the Northern Co-operative Society which, for well over 100 years, was the organisation to which the bulk of Aberdeen’s working families looked for groceries, furniture, clothes and much else?

But what does the future of what was once Norco House have to do with me? Not very much, I guess.

I’ve wondered if, for all the gains that came with North Sea oil, something was lost as well

I first got to know, and very much like, Aberdeen when I came there as a student in the 1960s.

But, though I haven’t lived in or near the city for more than 30 years, I’ve followed, from a distance, some of what’s gone on there. And I’ve wondered if, for all the gains that came with North Sea oil, something was lost as well.

That something being the self-reliance necessarily given up when so much of the Aberdeen economy became dependent on the activities of multinational companies headquartered in, and in the end controlled from, other places, far away.

That’s why I think that, if there’s to be a museum or some such centre located in what once was Norco House, it might be better for that centre to have an Aberdeen focus and to be in Aberdeen hands.

This centre’s task might be to help restore a sense of mission, and a sense of unity, to a place now unsure, or so it seems, of how best to move forward.

Aberdeen, after all, is a city that once built from scratch its own mile-long main street. But a city that, presently, can’t reach a consensus on something as straightforward as to whether or not a bit of that same street should be pedestrianised.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands