For those of us whose main preoccupation is books, the words themselves are rarely enough.

We are every bit as fascinated by the individuals and the industry that surrounds and supports them – the authors, their writing process (longhand or laptop? Shed or bed?), the agents, the commissioning, editing and publicising and so on. It is our inky, blinky equivalent of the Hollywood machine.

John Walsh’s new book, Circus of Dreams, has landed in these shabby circles with a whump. Subtitled “Adventures in the 1980s Literary World”, it is a thick, gossipy account of British literature’s most glamorous era, when authors became celebrities, advances soared, and every party and awards ceremony was feverishly detailed in the media. It was the decade that established Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, Pat Barker, Kazuo Ishiguro, Jeanette Winterson, Julian Barnes and William Boyd, to name only a few.

What really snagged me, though, were those novelists tipped for great things, who indeed enjoyed some success, but who have since quietly slipped into the gaping maw of obscurity. The 1983 Granta list of the best young British writers – the first of its kind, now repeated once a decade – included Ursula Bentley, Buchi Emecheta, Lisa de Terán and Clive Sinclair. No, me neither.

There’s nothing quite like unearthing an old, overlooked jewel of a book, the discovery of which confers bragging rights among the five or six people who might care, and so I decided to excavate these literary ruins.

Britain’s class structure for beginners

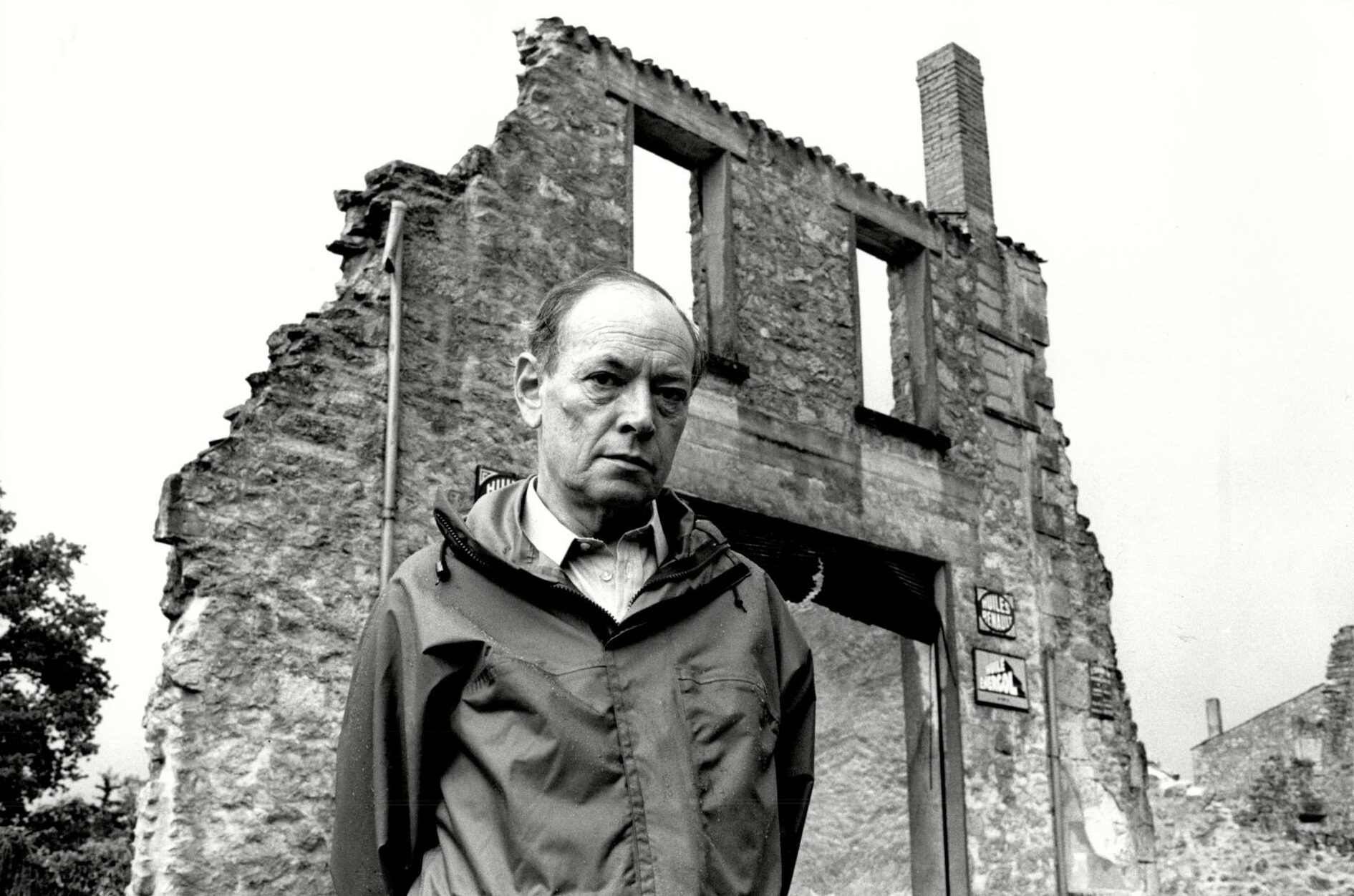

I ordered a bundle that had been mentioned by Walsh and that appealed to me, and I’ve just finished the first of them. You won’t hear David Hughes’s name mentioned much these days but, in the eighties, he was the real deal – his 1984 novel, The Pork Butcher, won awards for its fictional retelling of a Second World War massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane, where the Nazis locked villagers in their church and burnt them alive.

Hughes, who died in 2005 at the age of 74, seems to have had a rare old time of it before slipping into literary limbo – he published 11 novels, wrote TV programmes and films, was a visiting professor of writing at universities in Iowa, Alabama and Houston, and married and divorced a Swedish actress.

I suspect these works wouldn’t survive the reconstructed gaze of the 21st century but, for a young Scottish Central Belter, they were jolly good fun

It perhaps says rather too much about me that the Hughes book I ordered wasn’t The Pork Butcher, but its successor, But for Bunter. How could I not? As a child, I devoured the tales of Billy Bunter, the Fat Owl of the Remove, along with the Jennings and Derbyshire stories and pretty much anything else I could get my hands on that was set in an English boarding school and involved prep, tuck shops, ill-starred wheezes and stern, cane-swishing masters.

I suspect these works wouldn’t survive the reconstructed gaze of the 21st century but, for a young Scottish Central Belter, they were jolly good fun and (unwittingly) a window onto the class structure that underwires Britain to this day.

Bunter lives among us

Hughes’s book is the tale of Bunter all grown up. In this telling, Frank Richards, the author of the original stories, based Bunter on a boy called Archibald Aitken, who did indeed attend the notorious Greyfriars School in Kent. Still fat, greedy, selfish and preposterously bow-tied, Aitken is coming to the end of a long life and is determined to prove to the world that Billy Bunter was not just real, but a figure of note.

In adulthood, Aitken/Bunter has been a Zelig-like presence at many of the major events of the 20th century; a deus ex machina in the arrest of Dr Crippen, the sinking of the Titanic (he borrowed a set of binoculars that might have enabled the ship’s captain to spot an approaching iceberg), the General Strike and Suez. The Waste Land is a poem based on a patch of ground at the rear of the Bunter residence.

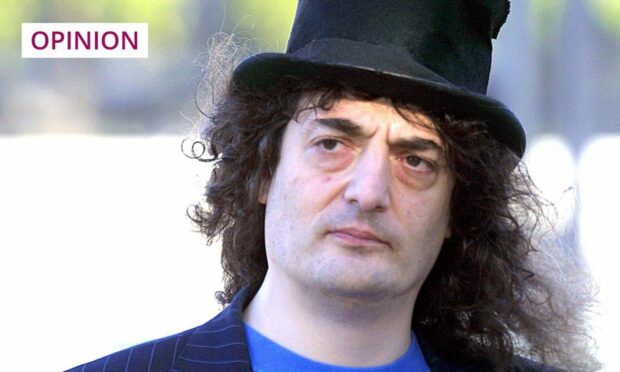

As I read on, I couldn’t help but draw the obvious parallel (you may have got there before me, dear reader). Bunter lives among us today. He remains the same overweight, gluttonous, selfish character, a blithe user and abuser of the class system and its networks, and he currently lives at 10 Downing Street.

The Banishing of Billy Bunter/Boris Johnson (1956)

The Boris Johnson act, with its cripeses and blimeys, its stuttering Latin, the leaps from the frying pan to the fire, the network of good chaps, could have been – indeed, was – scripted by Frank Richards and his like.

The Johnson con is awesome, both in its scope and its success

Even the titles fit: Billy Bunter’s Bargain (Brexit and a large majority for tolerance of total amorality), Billy Bunter’s Brainwave (let’s send refugees to… um… Rwanda), Bunter’s Last Fling (trousers round the ankles, fleeing yet another illicit bedroom), and Billy Bunter’s Christmas Party (the FPN’s in the post).

The Johnson con is awesome, both in its scope and its success. We have mistaken fiction for reality: Britain, an unserious, indulgent country, has elected a comic book cad as its prime minister and now seems to be stuck with him through penury and war.

The Banishing of Billy Bunter/Boris Johnson (1956) cannot come soon enough. Obscurity awaits.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland