As a schoolgirl in the Highlands, I sang pop songs in my bedroom and dreamed of glamour and attention.

I wanted to see the world, waft on beaches, swish among palm trees and float in azure pools. So, when Dingwall Academy advertised a cruise to Spain, Portugal and the Canary Islands, I was beside myself.

A cruise! An actual cruise! Wafting, swishing and floating here I come!

I worked all summer to pay for half of it, which, on a wage of £3 a day, was quite the feat and didn’t leave much over for a hot new capsule wardrobe of elegant cruisewear.

But, I was so excited that it didn’t matter; my navy gym shorts and M&S T-shirts would be rendered chic by the simple fact of being worn aboard a cruise liner and, if I added sunglasses – rarely seen in Ross-shire in the 1980s – you’d be hard pressed to tell me apart from Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday, especially when squinting in tropical sunshine.

Less swishing, more schooling

The glamour kicked off straight away as we were lined up outside Dingwall Academy and loaded onto a bus to Dundee, where we stood with hundreds of other kids in a giant warehouse before boarding the disappointingly compact SS Uganda, whereupon, instead of being shown up to our cabins, we were sent down to our dorms. Down. And down. And down.

Ours was so deep in the bowels of the ship that the walls were V-shaped; the floor almost ended in a point. We may have been inside the keel.

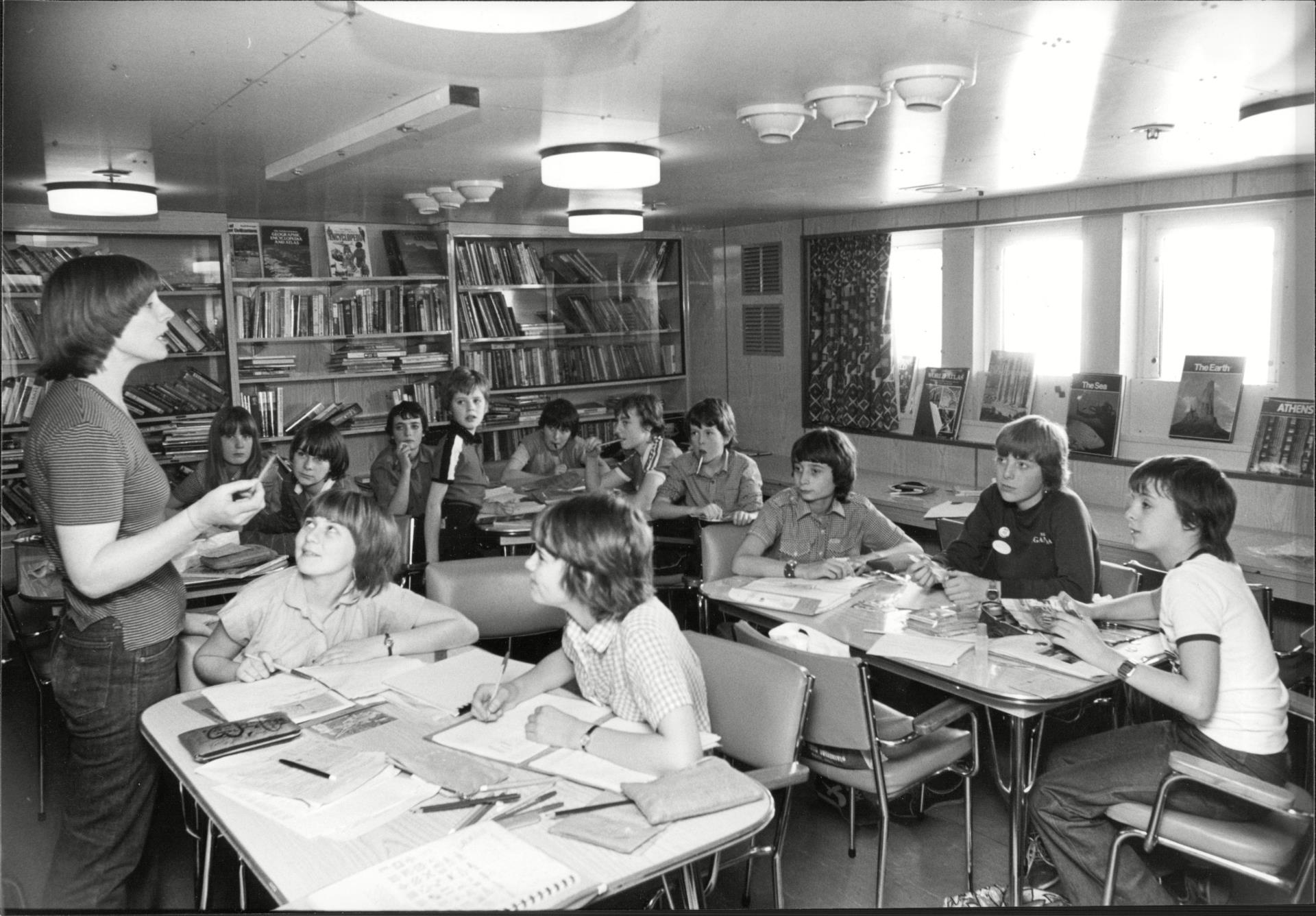

The SS Uganda was an educational steam ship and it appeared that my wafting and swishing would be regularly and rudely interrupted by classes throughout the day

We shared the dorm with girls from a school in the Central Belt. I can’t remember much about them apart from how loudly they roared with laughter when we claimed, in broad Dingwall, that we didn’t have an accent.

Perhaps I ought to have paid more attention to the reading materials we’d been given before signing up. The SS Uganda was an educational steam ship and it appeared that my wafting and swishing would be regularly and rudely interrupted by classes throughout the day.

No time for mischief

There wasn’t a cocktail bar but there was a sweetie shop, which was useful as there wasn’t any free time for spending our pocket money in boutiques during our stopovers. In fact, we were kept under rigorous supervision at all times, possibly because a child from another school went AWOL at our first port of call and the ship was delayed for hours until he was tracked down, distraught, convinced the boat had left without him.

Trips ashore were short. We climbed on bus after bus and went to learn about a thing. Prior to getting on the bus, we would have been sitting in a classroom learning about the thing and, after we got back, we had to write in our journals about the thing we had just learned about and seen.

Standing in a rainy Corunna square springs to mind, sketching the tomb of Sir John Moore, a man whose life story I had to Google in order to remind myself that he was, predictably, a British war hero.

We inspected hot lava springs in Lanzarote, then viewed the tempting golden beaches, with their imported Saharan sand, from the bus windows on the way back to the boat for our tea.

Stark reality versus starry-eyed notions

It wasn’t all bad. It was a privilege, of course, and fun in many ways, but so far removed from my starry expectations that I couldn’t help but grow keen to get home.

As the ship steamed up the river Tagus towards Lisbon, our final destination, with the huge statue of Christ bearing down upon us, I felt weary of it all. Weary, and inexplicably itchy. Very itchy indeed, in fact.

A glance in a mirror revealed no Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday but, rather, a wan, pink-faced Highland girl with a nasty dose of chicken pox. As if I needed reminding that we were all just a bunch of kids crammed into a small space.

I can forgive my younger self her starry-eyed notions. She didn’t have anything else to go on apart from movies, books and fantasy

My cruise ended in the ship’s hospital where at least I got the attention I craved – a visit from the ship’s captain, just like Audrey would have had, and a skive off the rest of the classes, much to my friends’ indignance.

I can forgive my younger self her starry-eyed notions. She didn’t have anything else to go on apart from movies, books and fantasy.

Now, when I look at kids pouring from school gates, I wonder about their own vast imaginations and dreams, and wish them better luck than I had in turning them into reality.

Erica Munro is a novelist, playwright, screenwriter and freelance editor