I had one of those moments of being overwhelmed at the state of the world recently.

It’s the sort of thing that can usually be precipitated by even a few minutes’ exposure to a social media feed, a glance at the headlines in the local paper shop, or an accidental brush up against breakfast TV.

Within 30 seconds, I’ve absorbed more brutal information than my brain can process properly:

- LGBT asylum seekers may be sent to Rwanda even though they would face sexual persecution there.

- Scientists warn that the climate limit of 1.5C is close to being broken.

- Russian troops using rape as a weapon in Ukraine.

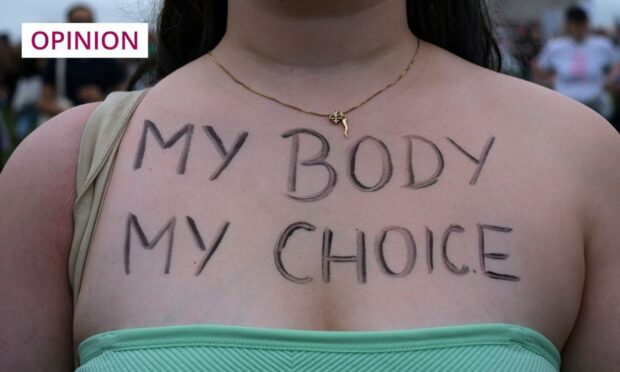

- The right to abortion may be about to be repealed in the US.

- The UK Government used the Queen’s speech to repeal the Human Rights Act.

- Elsie, in her 70s, skips meals and rides the bus all day to stay warm.

There’s more. There’s always more. It lines up, there at the scroll of a thumb, more and more and more bad news.

The cumulative effect – on me, anyway – is paralysing. I’m unable to look away, but I’m also unable to take any action (because where would I, one person, miles away from all of this, start?).

How did we get here? Where did it all go wrong?

A creeping, low-level dread has taken up permanent residence in my stomach in the past couple of months, refuelling itself every morning. I play with my kids, zone out and come to as they’re waving their hands in my face – I’ve been staring off into the distance, fretting endlessly about the world I’ve brought them into, the world they’re going to grow up in, unable to relax in the moment when everything seems so uncertain.

How did we get here? Where did it all go wrong? How on earth and on Earth can there be hope when contemporary humanity seems to be so brutally, selfishly destructive?

Humanity has always been awful and great

Strangely, the thing that actually helped me out of my most recent panic was remembering that humanity has, as a lumpen mass, always, always been this awful.

Last week, I read a newly-published book that I think will stay with me for a very long time. Homelands, a stunningly beautiful piece of writing by Scotland-based journalist, Chitra Ramaswamy, is a story of many things.

Happy publication day to Homelands by Chitra Ramaswamy

Design by @RafiRomaya

A book about migration, racism, resilience and what it means to belong.@Chitgrrl @canongatebooks pic.twitter.com/ZE0ErrPH0o— Canongate Art Dept. (@Canongate_Art) April 21, 2022

It’s the story of Henry Wuga, now in his 90s – a Jewish boy from Nuremberg who arrived in Scotland aged 14 at the start of World War Two on the Kindertransport (the scheme by which UK-based Jews sponsored Jewish children to bring them out of Nazi Germany). It’s the story of Ramaswamy’s parents, who emigrated from India to London in the 1970s to work the rest of their lives for the NHS.

It’s also about the friendship Ramaswamy forged with Wuga, finding understanding and near-familial love across their various cultural differences and a three-generation age gap.

It’s about the tiny kindnesses of strangers and friends that pepper both stories

But, most of all, as the title indicates, Homelands is a story about immigrants. About the people who are forced to leave the place they know as home, whether through persecution or in need of opportunity; about the forces that drive them to make that move; about the places they find themselves.

It’s about the intersection of the personal and the state: Wuga has researched the bureaucracy around his early life and arrival in Scotland meticulously to aid his friend in her telling of his life story.

It’s discomfiting, even at 80 years’ distance, to read of the eager Jewish schoolboy who loves to cook and still wears shorts being hauled out of school and into six different internment camps, where he shared quarters with actual Nazi prisoners of war.

It’s publication day for the astonishing, full-hearted, vital and moving Homelands. It’s about Henry Wuga, who’s 98 years old & came to the UK fleeing Nazi Germany, as well his friendship with @Chitgrrl. pic.twitter.com/VSLcOgORN4

— Canongate (@canongatebooks) April 21, 2022

It’s about Ramaswamy watching her mother, dying on a cancer ward in the middle of a Covid lockdown, “magically transform” into a person from another world in response to a junior doctor speaking her native language, Kannada.

It’s about Wuga and his wife, Ingrid, who also came over on a Kindertransport, finding their way to a sense of belonging within Scotland. It’s about Ramaswamy, a second-generation immigrant raised in London but who spent her entire adult life in Scotland, choosing, decades later, to name her children after Scottish glens to help forge their connection to the land she loves.

It’s about the tiny kindnesses of strangers and friends that pepper both stories; an all-too timely reminder that, even in the face of humanity’s worst behaviour, there are always those willing to look out for and reach out to those in need.

A timely and timeless reminder of the past

Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it; remembering the horrors of the Holocaust feels particularly pertinent right now, given our government’s attitude towards people fleeing similar persecution. But, it has always and will always be pertinent.

I allowed myself a wry smile at Ramaswamy’s note that the UK may take a lot of credit for the Kindertransport now, but the government actually only agreed to the scheme on the grounds that it would not cost them anything. The entire thing was funded and underwritten by Jewish communities in the UK and Germany.

I read echoes of the plight of contemporary child refugees, from Syria to Ukraine, in Wuga’s brief, emotional description of the cries of the youngest children on the Kindertransport, who were aged six and seven, being separated for the first time from parents most of them would never see again.

I’ve read reviews that said Ramaswamy could not have known how timely this book would be, presumably referring to the Ukrainian crisis, but I would counter that this book will never stop being relevant.

Humans may continue to brutalise each other, but they will also continue to connect. We start with the Elsies.

- Homelands: The History of a Friendship by Chitra Ramaswamy is out now, published by Canongate

Kirstin Innes is the author of the novels Scabby Queen and Fishnet, and co-author of the recent non-fiction book Brickwork: A Biography of the Arches

Conversation