As Britain takes a Platinum Jubilee break from its cost of living crisis, it’s increasingly evident that far too many of this country’s people are enduring scarcities of the sort that account for my one clear memory of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

This memory is all about a slab of chocolate.

Way back on that June day in 1953, I’d just turned five, and I’d been less than two months in school. My first weekday break from simple sums and sounded-out reading, then, was owed to the new queen’s crowning – a crowning that was to be celebrated in our West Highland locality, as far as we kids were concerned, by a cross between a sports day and a picnic.

This plan, like so many coronation plans, was jeopardised by the weather. As elsewhere in the UK, Coronation Day in the Highlands was, for early summer, exceptionally cold and miserable.

This resulted in the picnic element of our festivities being moved from an open field – where we’d engaged, I guess, in sack races, egg-and-spoon races and the like – to a nearby barn.

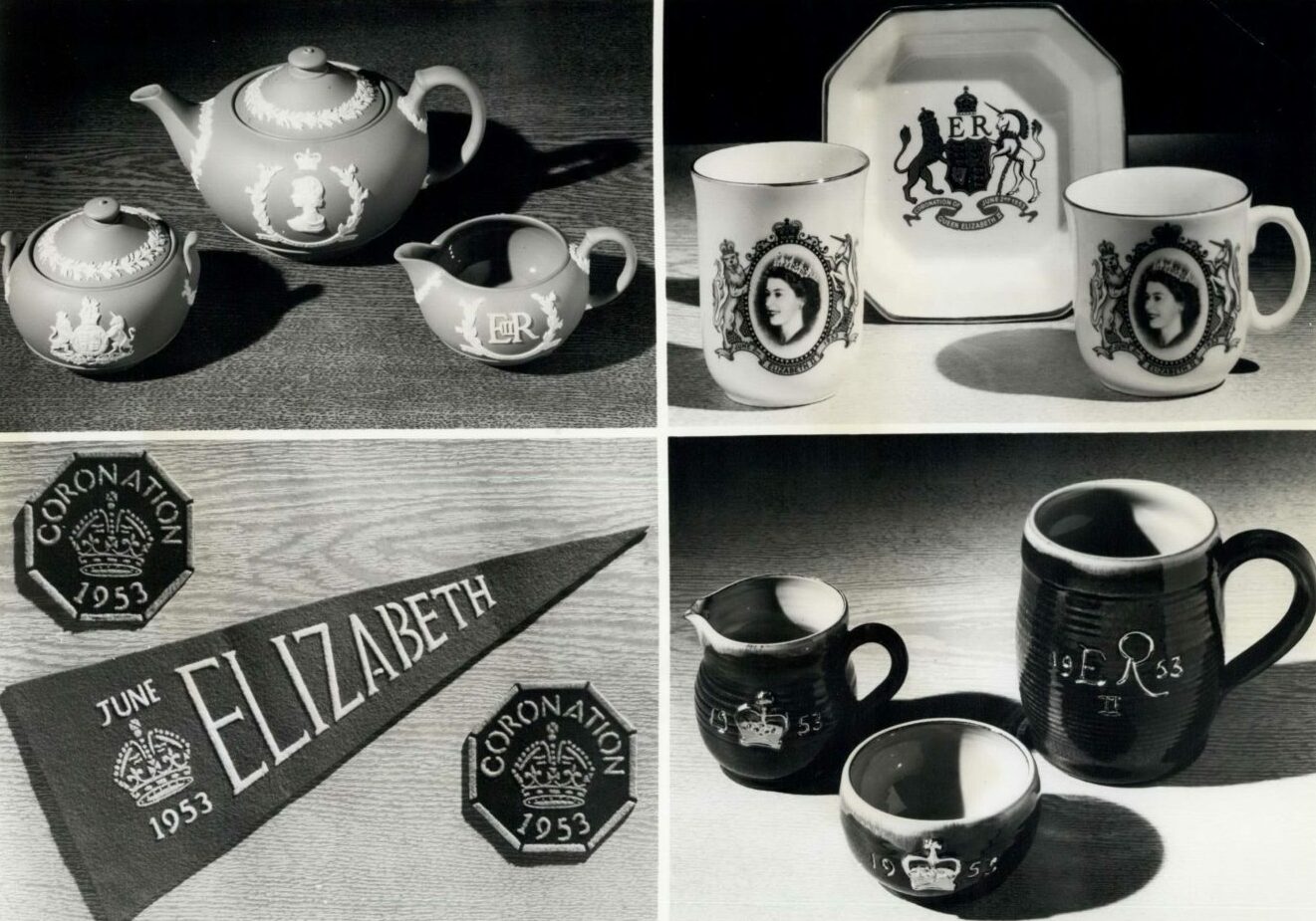

There, I presume, we’d have been treated to what was standard fare at all such 1950s occasions: homemade sandwiches and homemade cakes washed down with lemonade. I recall little of this. But, what I do remember vividly is being presented with a coronation mug featuring a portrait of Britain’s latest monarch.

So much more than a chocolate bar

The mug, to be honest, didn’t much interest me. What mattered was what it contained. Made instantly recognisable by its dark blue paper wrapper, and so big that it was longer than my coronation mug was tall, this consisted of a Cadbury’s chocolate bar.

Why my excitement? Well, I’d been born into a country where a child’s birth certificate was followed instantly by a ration book. And, when I was two, three and four, my allocated rations wouldn’t have extended to much in the way of frivolities like chocolate.

Food rationing had started in 1940 – not long after Britain went to war with Nazi Germany. But, victory in 1945 had brought no respite, the restoration of the country’s industrial economy taking priority over any resumption of unrestricted food imports.

The Britain of my early childhood, then, was a Britain where even the most basic essentials, such as bread and butter, could be bought only with the help of ration coupons. Monthly allocations of sweets were limited to just a few ounces per person. Milk chocolate, the kind that came in a blue wrapper of the type projecting from my newly obtained coronation mug, had disappeared entirely.

A lifetime on from my being handed my Coronation Day gifts, lots of Britain’s youngsters will see precious little in the way of chocolate bars or their modern equivalent this jubilee holiday weekend

Chocolate rationing, to be sure, ended two or three months prior to Coronation Day. But, such chocolate as had then made its way into our household, I suspect, would have had to be shared between me, my two-year-old sister and my parents. That Coronation Day chocolate bar – every detail of it with me still – was very probably, or so I reckon, the first such slab of chocolate that I could say was mine.

And in retrospect, perhaps, that same chocolate bar can be seen as an early pointer to the better times that were to open up for my baby boomer generation; times of increasing prosperity; times when we were granted access to educational and other opportunities of a kind our parents and grandparents couldn’t so much as dream about.

Growing poverty and runaway inequality

Those times are gone. Which is why, a lifetime on from my being handed my Coronation Day gifts, lots of Britain’s youngsters will see precious little in the way of chocolate bars or their modern equivalent this jubilee holiday weekend.

They, too, are living with food rationing. But not rationing of the 1940s and early 1950s type – rationing that applied to everyone, rich or poor, young or old, in ways intended to spread the burden of coping with shortage and with crisis. Nobody liked that sort of rationing. But at least it operated right across the board. It was, in essence, fair.

Today’s rationing isn’t like that. It’s a product of growing poverty and runaway inequality. Those going without in a country hugely wealthier than the country of 70 years ago are people whose incomes – whether wages or benefits – are insufficient to enable them to buy proper food, never mind treats, for their children.

Might it be possible for governments to respond to this emergency – and it is an emergency – by ensuring fairer shares for all? I don’t know.

What I do know is that far-reaching measures to combat inequality won’t be undertaken by an administration presided over by a man so lacking in any sense of solidarity with the wider public that, at the height of a death-dealing pandemic, he turned 10 Downing Street into a wine-stained, vomit-spattered venue for illegal partying.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands

Conversation