When we were 18 and in our first year at Aberdeen University, one of my closest friends told me she was pregnant.

It felt as though years of histrionic teen dramas had prepared me for this moment. Channelling Claire Danes in My So-Called Life, I grabbed her hand and asked with dramatic emphasis: “But… what will you do?”

“Well, of course I’m having an abortion,” she said, calmly, as though it was the obvious, logical answer. Which, of course, it was.

I was – am still – so impressed with her steeliness and determination to pursue this plan, even as the imposing patriarch GP at the university surgery tried, for some reason, to talk her out of it. “I just looked at him and told him, it is my right,” she said. “It’s just a tiny ball of cells at the moment. It’s not worth messing up my life for.”

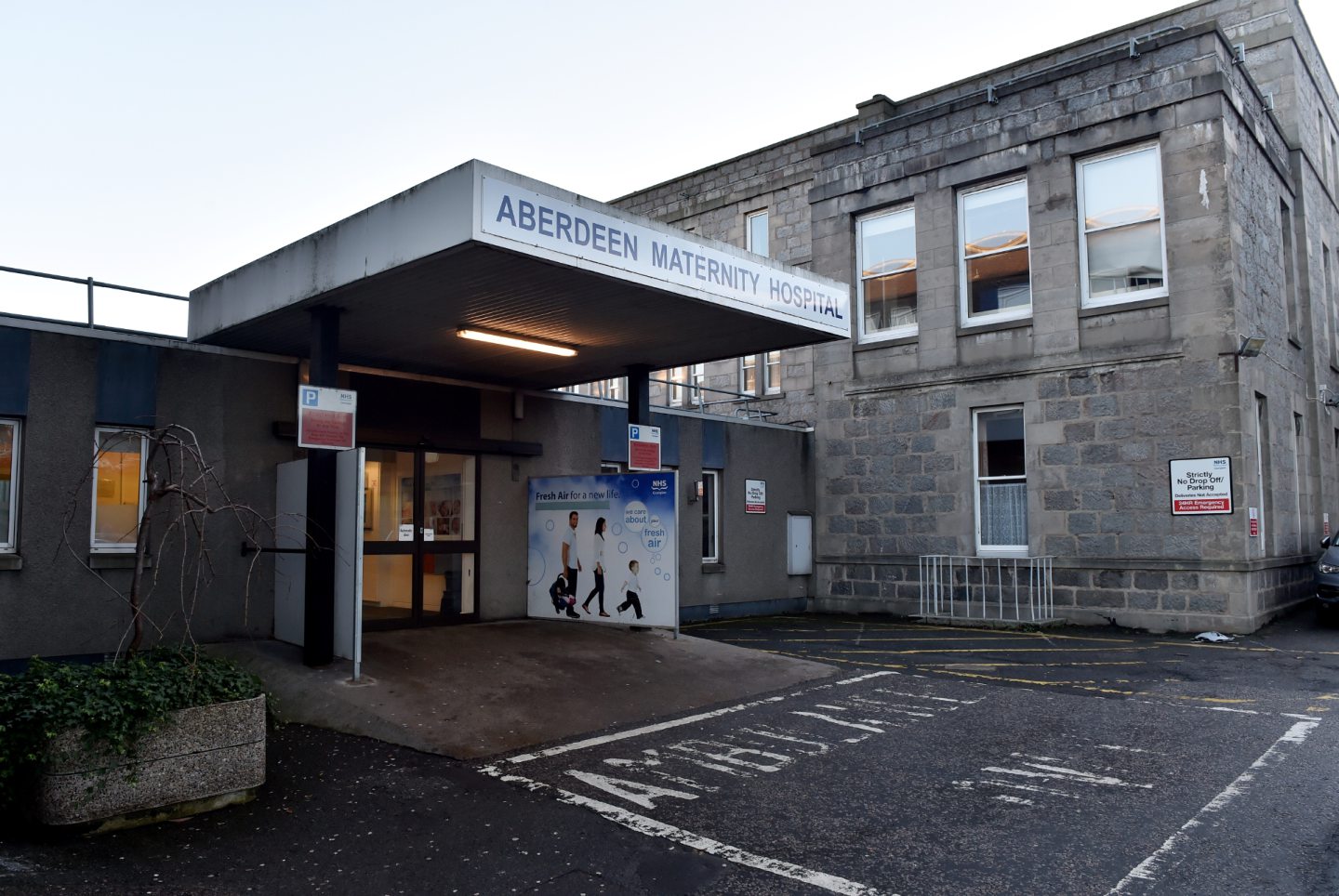

She came back from her outpatient appointment at Aberdeen Maternity Hospital eight days later sore, tired and free, untraumatised, and still completely sure that she’d done the right thing. We watched histrionic teen movies on the sofa under blankets until she recovered. She is now 40, with a loved, planned and wanted 10-year-old son.

Aberdeen Maternity Hospital has long been targeted by anti-abortion group

Sixteen years after my friend, I also went through a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. The circumstances were very different. I’d been taken to A&E in the middle of the night, after experiencing severe stomach pains due to the hugely, hugely wanted pregnancy I was miscarrying: my second IVF attempt after five years of fertility treatment.

I had been constantly monitored for the three weeks since the positive test, visiting a (different) maternity hospital for blood tests every morning before work. The day before, I’d received a phone call in the middle of a work meeting to say that the foetus’s numbers had dropped too low to make it viable.

Had I attended Aberdeen Maternity Hospital for that procedure, as my friend did so many years before, I might have looked out of the window of the ward the morning after the D&C, as I grieved and felt like my world was ending, and seen protesters holding up signs that told me God hated me, that what I’d done was murder, that babies were put to death on the premises. There might have been graphic images of foetuses, or baby handprints.

‘Because these are hospitals, not clinics, the people on those wards are more likely to be undergoing abortion of wanted pregnancies for medical reasons’

This is because, for some years now, Aberdeen Maternity Hospital has become one of the regular targets of the Texan-backed Christian anti-abortion group, 40 Days for Life, whose tactics include harassing women and girls attending sexual health and maternity clinics. I might have been handed pink or blue rosary beads as I left, or a mocked-up NHS advice leaflet addressing me as “Mum” as I entered.

‘I can’t fathom the impact that it has on our patients’

“The maternity unit looks out over Cornhill Road, which is where the protestors gather,” explained Lucy Grieve, who runs Back Off Scotland, a campaign group aiming to get 150-metre buffer zones established in law, meaning protesters would not be allowed to gather around hospitals and clinics providing abortion.

“The signs can be seen from the windows and, because these are hospitals, not clinics, the people on those wards are more likely to be undergoing abortion of wanted pregnancies for medical reasons,” she told me.

“The protestors stand right where the bus comes in; anyone coming in has to run the gauntlet of these signs. It’s a political commentary right as you step off the bus.”

🚨 Scottish Government u-turn 🚨

The Women’s Health Minister @MareeToddMSP’s handling of the buffer zone issue has been dismal and we are grateful for strong words of support from FM @NicolaSturgeon.

We need national buffer zones now. https://t.co/7OeWttMOfs pic.twitter.com/9720hRdfR6

— Back Off Scotland (@backoffscotland) June 9, 2022

Grieve passed me on the testimony of one member of staff employed in the building, who said: “I’m a soon-to-be retired midwife who worked in pregnancy loss for two years. I’m shocked that this is allowed and can’t fathom the impact that it has on our patients when accessing legal healthcare.”

Telemedical abortion, where the patient takes two pills at home, has become more common for early stage abortion than surgical procedure in the past few years; as Grieve says: “The people attending the maternity hospital for surgical abortion are likely to be amongst the most vulnerable – the ones who need to be seen by a doctor because there is a medical need.”

No one should be forced into pregnancy

The fact of the matter is, though, that there are not two different “kinds” of abortion; one where surgical intervention is necessary to stop a non-viable, wanted pregnancy, and one where, say, an 18-year-old girl chooses not to drop out of university to support a baby she doesn’t want as a single mother. There is only the right to bodily autonomy.

It would have appalled and traumatised me to have run such a gauntlet when I underwent my own D&C, but it could also have a similarly traumatic effect on someone who was unable to keep a pregnancy for non-medical reasons.

No one should be forced to endure a pregnancy they do not want. And, fortunately, in this country we still have laws that recognise that fact

Having now carried two pregnancies to full term, and understanding the entire, devastating physical, mental and emotional toll they took on my mind and body, even though these were pregnancies I wanted, I’m even more persuaded that no one should be forced to endure a pregnancy they do not want. And, fortunately, in this country we still have laws that recognise that fact. It is our right.

If protestors are unable to respect that, then there needs to be legal protection. Bring on the buffer zones.

Kirstin Innes is the author of the novels Scabby Queen and Fishnet, and co-author of the recent non-fiction book Brickwork: A Biography of the Arches

Conversation