I voted for Scottish independence in 2014.

I was a strong advocate and, eventually, quite single-minded about it, having swithered on the topic for a few years before that. I was, admittedly, crushed when the Yes campaign lost the argument and the referendum, having come to believe that independence was the best foot forward for the country.

A repeated statement over the last few years has been that the matter is settled for now, sometimes based on then-First Minister Alex Salmond’s assertion that the referendum was a ”once in a generation opportunity”. Boris Johnson harked toward this just the other day, while being interviewed by Sky News – “the decision was taken by the Scottish people, just a few years ago, within recent memory”.

It sometimes seems tawdry to say “a lot has changed”. In politics, “a lot” can happen rather, well, a lot, and “a lot” might be tied to one’s relative political awakening, or more frequent digestion of the news cycle. But, it has definitely been a busy few years, particularly since 2016.

“A lot” also might also be used to justify either one position or the other, depending on your political leaning. Enough has happened, say Brexit and the rise of a new Tory party, to necessitate another referendum. Or, enough is happening – the war in Ukraine, the not-quite-over pandemic, and a recession – to not rock the boat any further.

I look back on 2014 and I think about my personal position. Rather than a determination, I remember bits of conversations. Discussions, we’ll call them. Keenly, I remember a chat with a pal about whether the rest of the UK might remove us from the EU. They felt that this was unlikely. I disagreed. It was peak Farage time, and it made me far more pro-independence than I may otherwise have been.

We all like to believe we choose our political positions for the greater good

The idea of being separated from the EU and Brexit had been intertwined with my belief that independence for Scotland was best. We all like to believe we choose our political positions for the greater good.

I believe strongly in the free movement of people who are inclined to move. But, the personal always becomes political as well, and I had a Polish partner from late 2013 until recently. Exiting the EU would have a direct impact on choices we could make later in life.

Scotland should strive for achievable improvement

In the post-Brexit landscape of 2022, the Scottish Government has started a new campaign for Scottish independence with EU-living firmly at the centre of it. The paper produced last week – called Wealthier, Happier, Fairer: Why Not Scotland? – focuses chiefly on comparisons of quality of life between small, nearby and northern countries, and that of the UK.

I’ll admit that I was slightly underwhelmed by the paper on first read; in a sense, these are a re-run of arguments made prior to 2014, and often since. The charts and graphs give the impression of a UK that isn’t doing as well as some of the leading per capita economies in the world – but who is? That isn’t to say that Scotland shouldn’t strive for improvements that can be made.

Where the paper really finds its strengths, I think, are in its points around the labour market. How these comparator countries tackle income inequality, the gender pay gap, in-work poverty and long hours, sick pay, and social security payments. Swedish job security councils and Danish disruption councils transform the skills base there.

The key is attacking the current UK Government on what it truly doesn’t do well – looking after those who do the hard work, and taking care of the most vulnerable. This is how you transform a society.

Have opinions changed?

I think I feel the same way as I did about independence in 2014, despite changes in both the political situation and personally. I know a lot of people who decided that Scottish independence might be best following Brexit.

However, I also know some who voted for Scottish independence at the time, seeing it as a vehicle to exit EU regulation – a feeling not uncommon in the north-east and its fishing communities. How would these folk vote now?

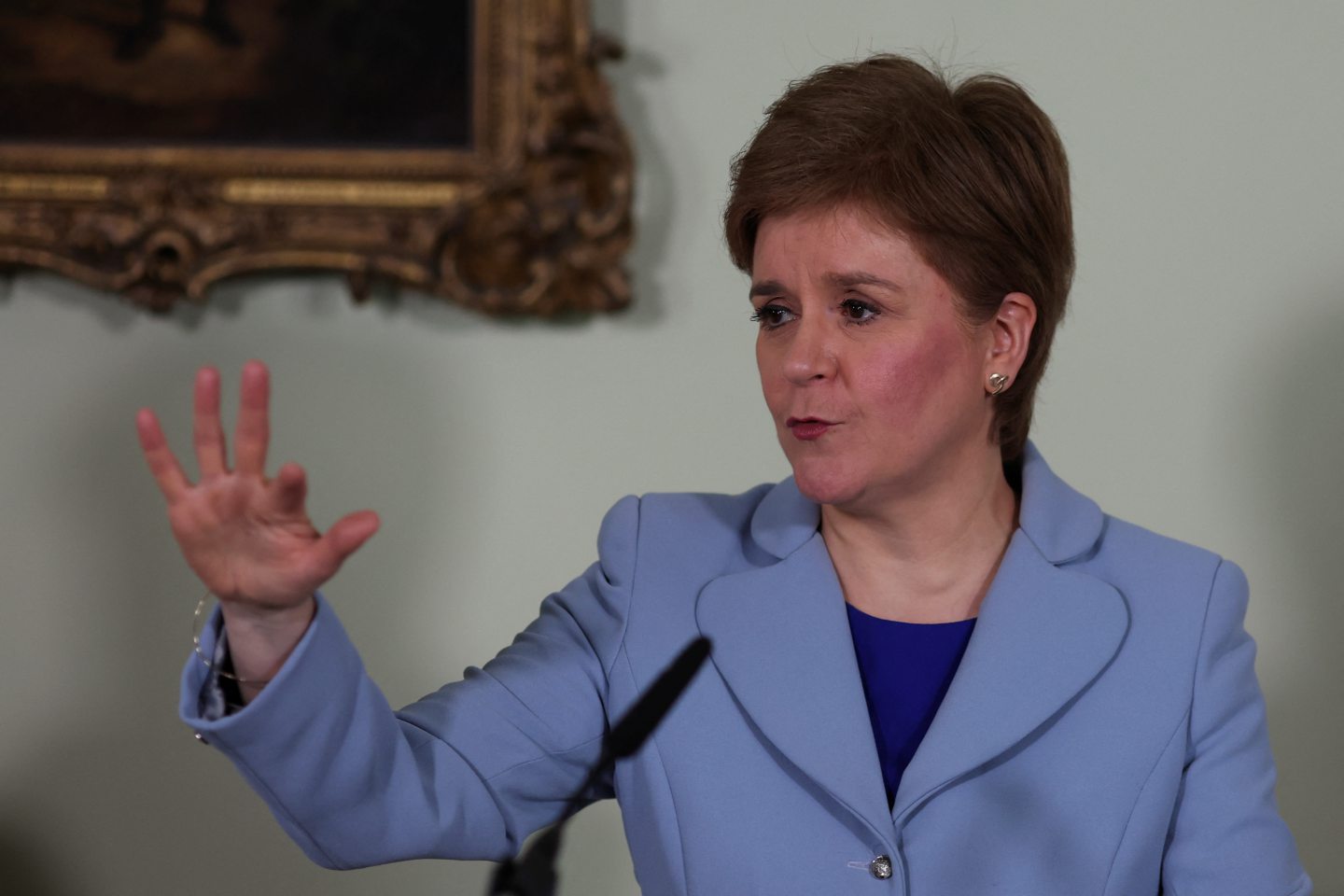

Last week, Nicola Sturgeon asserted that it would have made an inarguable difference in 2014 if the people of Scotland had known Brexit had truly meant Brexit only two years later. That may be the case. But, hindsight is a funny thing, and 2023 is not 2014. The horse has already bolted, and it might be that voters don’t want to reopen the stable door.

In October 2023, if legal processes can be ironed out, there will be another referendum. This paper, and the ones that will follow, is a sober start to that, rather than the bombast of before. That feels appropriate given the state of the world.

Before next year, the first minister will need to tease out the arguments in favour of independence for voters who might be more cautious than we think.

Colin Farquhar is head of cinema operations for Belmont Filmhouse in Aberdeen

Conversation