Few of us are keen to pay more tax.

Increasingly, though, it looks like something we will all have to get used to, one way or another. Particularly in Scotland.

The current cost of living crisis, as we face rising bills for heating, the weekly shop and mortgages, is causing pain across the nation, and will cause more as the year goes on.

Important parts of our wealth-creating private sector – particularly retail – are struggling to recover from the Covid-inspired lockdown and changes in our consumption habits. Government debt has soared, due to the many billions spent protecting us from Covid, such as through the furlough scheme, and now on cushioning us through the downturn.

But, as hard as all this has been, the economic storm clouds continue to gather above a future that will require big and difficult decisions to be taken by our political leaders.

One reason for this is that Scotland’s population is ageing rapidly – faster than the UK’s as a whole – at the same time as our working-age population is shrinking. This means that a smaller group of younger and middle-aged people are having to fund public services that are being used by a growing number of elderly.

It’s towards the end of life that we come to rely on the state more heavily – the NHS, the old age pension, social care – even though we are, by that point, contributing much less to the public purse. By the time the current working generations are ready to retire, their successor workforce will be smaller still, and the pressures even greater.

Current tax system is not fit for purpose

Inflation and the extra demands on spending mean we have to raise ever more sums just to keep public services in their current, often sub-optimal condition. But we will need to do better than that.

For example, the NHS has a huge backlog to get through, is able to treat a broader range of conditions than ever before thanks to research breakthroughs, and can use technology to keep us healthier – but this is expensive.

The Scottish Government is set on introducing a costly programme of care for the elderly, which will require a whole new pot of money to be found. And, tackling climate change – surely a non-negotiable – will require vast amounts of public spending.

If we are to fulfil all these tasks, we can’t simply ask the same shrinking group of people to keep paying ever higher sums of tax in the same way. Which is why my think tank, Reform Scotland, has published a paper looking at how we might better and more innovatively use the tax system in a way that is more fit for purpose in the modern world.

The paper’s author, Heather McCauley, is a global public policy expert and former senior civil servant, who has worked with the Holyrood and Westminster governments, and advised a number of prime ministers in New Zealand.

Simply raising taxes isn’t the answer

McCauley makes the argument that nothing less than a redesign of our tax system is needed. As she points out, “public debate often focuses on spending choices, but decisions on how much tax revenue a country needs, and the way governments raise that revenue, have as much impact on people’s wellbeing as the way in which revenues are spent.”

There comes a point where further increases to taxes on wages are simply unfair and self-defeating

When we need to boost revenues in Britain, the ingrained habit is to tweak income tax or National Insurance. But there comes a point where further increases to taxes on wages are simply unfair and self-defeating.

McCauley argues that, instead, the UK and Scotland will need to broaden their existing tax bases or tax new things, and probably do both. Here, Scotland has a choice to make – high-spend countries such as the Nordics are generally also high-tax countries, but other countries, like New Zealand, raise significant revenues with lower tax rates, if their taxes have a very wide base and few exemptions.

We must reconsider wealth

Another consideration is moving to a system of wealth taxes. Taxes on the ownership of wealth are relatively economically efficient, help encourage positive wealth creation rather than “passive” wealth accumulation, and are essential in tackling wealth inequalities.

But there is always a danger of capital flight if a country is felt to be overly hostile to the wealthy. Therefore, the paper suggests Scotland should focus on immobile wealth.

McCauley says there is a strong case for replacing the SNP’s Land and Buildings Transaction Tax, which itself replaced stamp duty in 2015, with a land tax, as well as reforming council tax by moving payment from occupiers to owners, and aligning rates more strongly with property and land values.

Greater flexibility for taxes to be imposed at a local level might also help. On top of this, the healthiest tax systems are subjected to independent “root and branch” reviews every five or 10 years.

This is a conversation Scotland needs to have – one that it cannot avoid. And, it requires Nicola Sturgeon’s government to have a frank and grown-up conversation with the electorate. It’s time we got started.

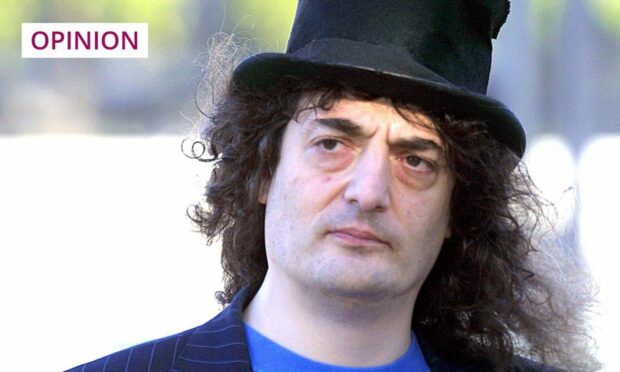

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation