AT this stage, all we can say for certain is that there is to be a fight.

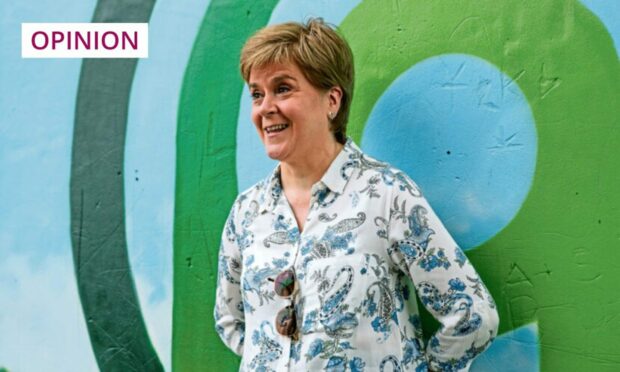

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon may have announced plans to hold a second independence referendum on October 19, next year, but it seems unlikely she has the authority to proceed with a vote on the constitution without the permission of the United Kingdom Government.

That question will now be considered by the Supreme Court.

If the court rules, as many legal experts predict, that the First Minister may not, in fact, deliver her promised plebiscite, Sturgeon’s fallback plan is to treat the next available General Election as a “de facto” referendum.

It’s clearly wrong that there can be no clear route to a second referendum.

Since there is no such thing as a “de facto” referendum, Scottish nationalists may – soon – be contemplating the reality that Sturgeon’s bridge to independence isn’t even half finished.

Legally-established vote recognised by all

The 2014 referendum is considered to be gold standard by Sturgeon. That legally established vote was recognised as legitimate by all participants. Neither of the First Minister’s current options – a referendum without Westminster permission or a General Election that would be treated as a referendum – look likely to achieve that status.

Which brings us back to the other, often suggested, route to a referendum.

The SNP line has long been that it would be perfectly willing to work with Labour (or any other “progressive” party) in order to lock the Conservatives out of government.

The hypothesis runs that, should a general election result leave Labour just short of a majority, the SNP would be willing to cut a deal. All the nationalists would require in order to put Labour into power would be the right to hold another referendum.

Scottish independence referendum dominated in 2014

The flaw with this theory is that the SNP would have nowhere to turn if Labour refused to play ball. What would the Nats do? Would they really put another Tory Government in power?

It’s clearly wrong that there can be no clear route to a second referendum. Even those most committed to the maintenance of the Union must see that democracy demands there be some process by which another referendum can take place.

.@Ianblackford_MP: "Mr Speaker, Scotland’s First Minister has set the date and started the campaign

Our nation will have its independence referendum on the 19th of October 2023." #PMQs pic.twitter.com/FyqJ35Cp8A

— The SNP (@theSNP) June 29, 2022

But for now, no such mechanism exists and there is no appetite among Unionist politicians at Westminster to change that situation. Who can blame them?

For six months in 2014, the question of Scottish independence didn’t just dominate our politics, it dominated the politics of the UK. Your average voter, south of the border, might – not unreasonably – think Scotland has had its moment in the spotlight for the time being.

Do voters in Doncaster or Bristol or Salford want their MPs bogged down in another constitutional battle while they fear for their livelihoods? I suspect they do not.

And if that is so, Nicola Sturgeon will be waiting a long time until she finds a single ally, among her Westminster opponents, in her fight to establish her dreamed of second referendum.

Euan McColm is a regular columnist for various Scottish newspapers

Conversation