Next week sees the annual ritual that is the release of the Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (Gers) numbers.

Why a ritual? Because the statistics show us how much money is raised through taxation in Scotland versus how much is spent by government, which means it feeds directly into the independence debate.

Here is how the ritual usually plays out. The numbers, which are produced by Scottish Government statisticians to exacting standards, show Scotland running a large deficit, which suggests the new state would start off in a difficult economic position. This is pointed out by those arguing against the break-up of the UK.

Those arguing for a Scottish exit then react by either dismissing the numbers or deflecting from the economic arguments by claiming the real problem is with those pointing out the reality. If only the naysayers really believed in Scotland, then all would be well.

The numbers from last year were startling. Scotland ran a deficit of over 22% of GDP, or £36 billion. Total public expenditure in Scotland hit almost £100 billion, off the back of the UK Government ramping up spending to deal with the Covid emergency. Revenues generated in Scotland were around £11,500 per person, while government spending was over £18,000 per person.

Independent Scotland in 2014 would have been an economic disaster

Recent years have, of course, been exceptional. A typical year prior to the onset of the pandemic would see Scotland running a deficit of around 8 to 10% of GDP. That is still very high, and would be considered unsustainable for a state to maintain for anything but a relatively short period of time.

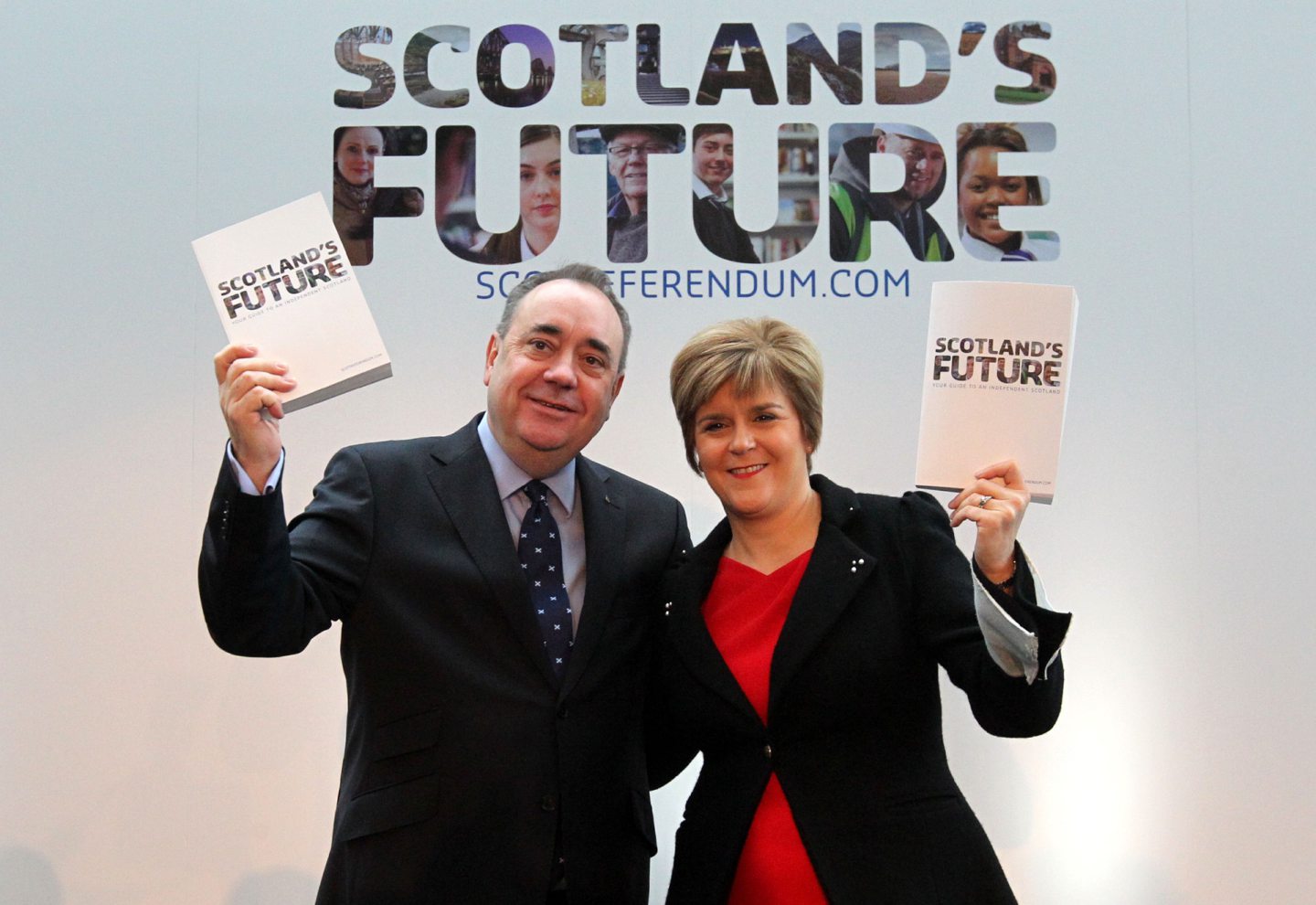

With numbers like that, it is sobering to think what position Scotland would have been in had we taken the lead of Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon in 2014 and voted to exit the UK.

Scotland would have become independent in March 2016 under the Salmond and Sturgeon plan. The new state would have started with a deficit of at least 10% of GDP, as per the Gers figures for that year, and that’s before taking account of a deteriorating tax base as people, money and companies likely left the country in the build-up to secession.

The new Scotland would have had no currency of its own and no central bank that could do quantitative easing (where the central bank creates money to buy financial assets, usually government bonds, thereby helping to stimulate the economy). It would have been trying to issue vast amounts of bonds in sterling, now a foreign currency, with no credit history, and with macroeconomic fundamentals that would make a hedge fund manager spill his coffee.

Scotland becoming the first part of an advanced economy to cut itself off from its central bank and currency base, and from its Treasury and established tax base, would have been a disaster

In short, Scotland becoming the first part of an advanced economy to cut itself off from its central bank and currency base, and from its Treasury and established tax base, would have been a disaster. It would almost certainly have induced a severe economic crisis, starting in 2016, which would have put Scotland in an impossible position just a few years later, when the biggest spending challenge in generations presented itself in the form of Covid-19.

Sturgeon and her colleagues have told us to ignore statistics

Last year, I interviewed a senior economic advisor to Switzerland’s central bank, Professor Cédric Tille, on the currency implications of Scotland exiting the UK.

Professor Tille has no dog in our constitutional fight. He is completely impartial, as well as being an exceptional macroeconomist. He could not have been clearer. He said that if Scotland breaks away from the UK, then the first prime minister of the new state had better have a good relationship with the International Monetary Fund, because they could find themselves having to submit an application for a bailout.

It is worth keeping all this in mind when the new Gers numbers come out next week. In recent years, Nicola Sturgeon and her colleagues have told us to ignore the statistics, as they only inform about Scotland’s position within the UK. To some extent this year (and especially next year) that could seem ironic, as North Sea revenues temporarily jump to healthy levels on the back of hydrocarbon price hikes and windfall taxes on producers.

That aside, what Gers definitively does do is provide us with the best set of statistics for projecting the starting point of the new state. In the unlikely scenario that Scotland actually secedes, those asserting the irrelevance of Gers would have a rude awakening when investment banks start using the stats to price up debt for the new Scotland – with a hefty risk premium added to cover the real risk of default.

Gers is relevant, then, and we should use the numbers as part of a process of evidence-based analysis when assessing independence. A strong dose of radical realism is needed in a debate often deliberately clouded in reality denial.

John Ferry is a regular commentator on Scottish politics and economics, a contributor to think tank These Islands, and finance spokesperson for the Scottish Liberal Democrats

Conversation