I don’t think I’d ever know how many days any month has unless I’d learned that old rhyme as a child:

“Thirty days hath September, April June and November. All the rest have 31, except February alone which has 28 days clear, and 29 each leap year.” It’s not the easiest thing to learn but, once done, it’s there forever.

And I’m not sure I could count, either, unless I’d learned that one, two, three, O’Leary; four, five, six, O’Leary; seven, eight, nine, O’Leary; 10, O’Leary caught it… Although the dear man was no Irish hurler, apparently – the word having been changed from the original “aliry”, a mid-14th century term meaning “crooked legs”.

I’ve always enjoyed the Scots version which went something like: “One, two, three, O’Leary, I saw Kate MacLeary, sittin’ oan her bumbaleerie, eatin’ chocolate biscuits.”

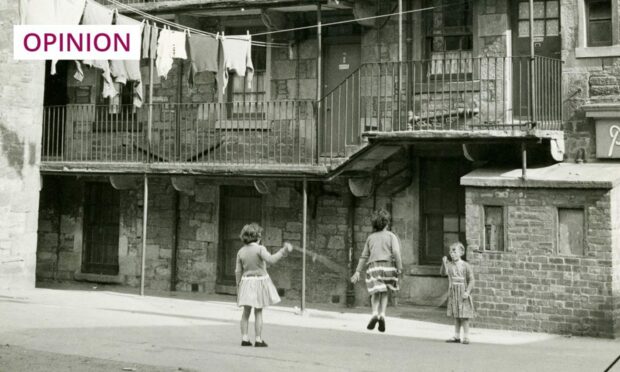

Which brings me to the wonderful children’s traditions of replacing acceptable words with naughty ones. “Bum” was always a favourite. This, recorded from a young Dundee lad in 1959: “No last nicht but the nicht afore, three black cats cam’ roarin’ at the door. Ane got whisky, ane got rum, an’ ane got the dishclout oe’r his bum.”

Rhymes spread and recorded the news

Iona and Peter Opie did fantastic work over many years, researching and recording children’s rhymes the length and breadth of Britain, and it’s always a delight to dip into their books, The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren, published in 1959, and Children’s Games in Street and Playground, from 1969. They tell a vivid social history.

The Opies themselves always marvelled at the way words and rhymes and news travelled, long before the internet came along.

For instance, at the time of the abdication in 1936, this fine two-liner appeared: “Hark the herald angels sing, Mrs Simpson’s pinched our king”, recorded throughout the country just days after the constitutional crisis was in the news.

What particularly interests me about these children’s rhymes and songs and games is the way they reflect the social and political events of the time. Just as we’re all today wired into the world wide web, so in those days news travelled fast. One thing turned into another.

I wonder if the royal events of these days have already made their way into the (virtual) playground? “Thousands standing in a queue, to bid the Queen farewell. God be with her, and adieu, in glory she will dwell.”

‘Ma wee man’s a miner, he works at Ferryhill’

One of my favourite collections was done by Dr Robert Craig MacLagan, an Edinburgh surgeon who published The Games and Diversions of Argyleshire in 1901. He speaks of several Gaelic games which have, unfortunately, disappeared nowadays.

I like it when local topography is used, so that Ardrishaig, for example, takes the place of London

They were simple games, in the sense that they used the natural materials to hand: bits of grass, stones, sticks, pebbles and so on, though some mention more “modern” means such as “an india-rubber ball”.

I like it when local topography is used, so that Ardrishaig, for example, takes the place of London: “Oh, what is Mary weeping for, weeping for, weeping for? Oh, what is Mary weeping for, upon Ardrishaig pier?”

And, just to show that sensationalist tabloid news mixed with the commercials of the day made as much impact then as it does now, they also had this rhyme in Kintyre: “Jack the Ripper’s dead, and lying on his bed. He cut his throat with Sunlight soap. Jack the Ripper’s dead.”

They tell of social conditions with good humour. In Aberdeen, for example, kids chanted this: “Ma wee man’s a miner, he works at Ferryhill. He gets his pey on Setterday and buys half a gill. He goes to church on Sunday, a half an hoor late. He pulls the buttons aff his shirt and puts them in the plate.”

Last is the luckiest

Counting-out rhymes are fascinating because they are so universal: these consist of “nonsense” words which have a remarkable similarity wherever recorded.

In Aberdeen, for instance, an 11-year-old girl chanted: “Eeny, meeny, macca, racca. Rae, rye, doma, anca. Chicca, racca, Old Tom Thumb”, while an 11-year-old girl in Wellington New Zealand chanted: “Eeny, meeny, macka, racka. Rare, rye, domma nacka. Chicka pocka, ellie focka. Om, pom puss.”

If you can’t run fast, you might win hopping on one leg, or running backwards, or sideways or rolling along

In Bergen in Norway, children skipped to this: “Ina mina maina mau. Katta lita bobbi sau. Di va noksa gau. Ina mina maina mau.”

But, I think the best thing I learned from the Opies’ books is this: that children are far less competitive than adults. Their games, though fierce, are designed so that everyone wins at one time or another. For example, if you can’t run fast, you might win hopping on one leg, or running backwards, or sideways or rolling along.

Everyone is given a chance. They even have a saying for it: “First is the worst, second is the next, last is the luckiest.”

How lucky am I?

Angus Peter Campbell is an award-winning writer and actor from Uist

Conversation