The magnitude of the Queen’s death naturally obliterated other news events, but there is another tragedy I won’t allow to pass by without commenting.

I was enjoying a coffee in town until a newsflash popped up on my mobile phone that television journalist and Classic FM presenter Bill Turnbull had died.

We’d known for some time he was terminally ill with prostate cancer; he told us. It was a courageous thing to do.

He put on a brave face and tried to remain active, so his death at 66 still came as a shock to me.

The sudden death of rugby star and commentator Eddie Butler – while fundraising in Peru for Welsh prostate cancer, the day before Bill’s funeral – also shone a light on this issue.

There were warm tributes to Bill from P&J readers.

I followed his struggle with great interest for one reason in particular. We had quite a lot in common, even though our early lives were starkly different.

I sauntered into the surgeon’s office thinking: ‘Cancer? Me? No chance’

Son of a City barrister with Scottish lineage, Bill went to Eton; son of an impoverished Irish immigrant, I went to a rubbish secondary modern school.

Health issues cut across social boundaries, so we shared a mutual bond of which Bill was completely unaware. Both of us were diagnosed with prostate cancer a few months apart, in 2017. I survived (touch wood).

My brother’s early warning saved my life

It makes you think about mortality, fate, how the cookie crumbles, or however you prefer to describe it.

But, with cancer, there is a powerful factor much more decisive than a haphazard roll of the dice, which allows fate to take its course: early diagnosis and intervention are often the difference between life or death.

There will be a moment of applause to honour Eddie Butler’s life across this weekend’s URC games 👏

🎙 Eddie Butler | 1957-2022 🤍 pic.twitter.com/rGLgd2RFSw

— BKT United Rugby Championship (URC) (@URCOfficial) September 23, 2022

It was a few minutes before noon on February 16, 2017 when I sauntered into the surgeon’s office thinking: “Cancer? Me? No chance.”

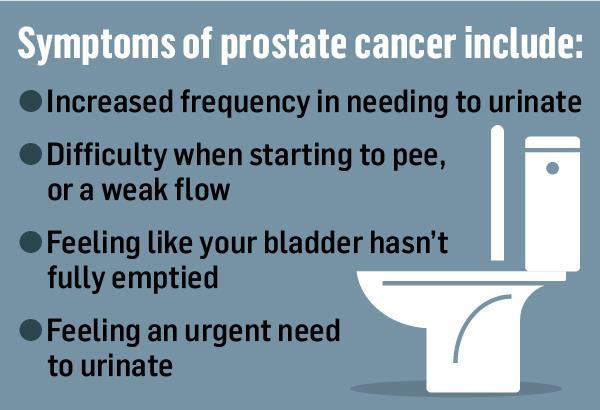

I was always lucky – my personal guardian angel saw to that; I had no symptoms, felt great, as a matter of fact. The surgeon was smiling, but his first words told me I had cancer.

I sat on a bench outside the Aberdeen hospital staring forlornly into space.

Sadly, Bill’s cancer was identified late, danger signs missed

But I had some things going for me: my brother in Melbourne tipped me off that his cancerous prostate had been removed, so I should get checked. This was significant, as the risk factor zooms among siblings.

His early warning saved my life, before it spread beyond the point of no return.

Getting men to see a doctor has always been a problem

A brilliant health advert now on TV reminds me of it. The one where an actress, looking a bit like a vampire, plays the part of a malignant tumour which has just set up home in someone’s lung. She says something along the lines of: “I like it here, maybe I’ll move in next door, too.” (Meaning the other lung.)

Sadly, Bill’s cancer was identified late, danger signs missed. It had spread beyond his prostate, so it became a matter of prolonging life rather than providing a lasting cure.

Luckily, mine was nipped in the bud: removed with my prostate before it could break out and go on the rampage.

Getting men to see a doctor has always been a problem, of course. Harder now, as it’s not so straightforward to see a GP post-Covid – new default email and telephone consultations might put men off.

And, on top of that, are all the hospital backlogs.

Prostate cancer diagnosis fell back sharply in the UK during lockdowns, due to messaging about protecting the NHS combined with inherent male reluctance to come forward. But early screening and intervention are vital; prostate cancer remains one of the biggest killers of men.

‘Getting Prexit done’ wasn’t straightforward

I was keen to “get Prexit done”, so I assumed blithely that I would, of course, be one of up to 90% of men who returned to normal functioning months after parting company with their prostates. I was destined to be one of the unlucky 10% who don’t recover fully from this major surgery.

The cancer was banished, but I was left with permanent debilitating collateral damage, which is a known risk. I rage, but how can I feel sorry for myself when faced with the alternative?

Nothing is straightforward about prostate cancer.

It’s located in a very awkward place, for a start; like trying to retrieve a 50p coin lodged somewhere in the bendy drainpipe under your kitchen sink. Even the two highly-invasive biopsies I underwent in the process carried known risks.

But, any clearly-defined surgical risks have to be weighed against a strong probability of dying – at a relatively young age, in many cases – if you do nothing.

I was lucky: without being warned, I might have died, like Bill, this summer.

I survived, or maybe I should say that I am “currently surviving”.

With the woman in the advert in mind, my post-op screening shows it hasn’t taken up residence again.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal

Conversation