I’ve never really understood some folk’s antipathy towards Gaelic.

After all, it’s not a weapon of mass destruction, or Liz Truss. And, though something like £30 million of public money is spent annually on the language, that’s only a wee dram compared to the glen-loads of distilleries spent on Beurla.

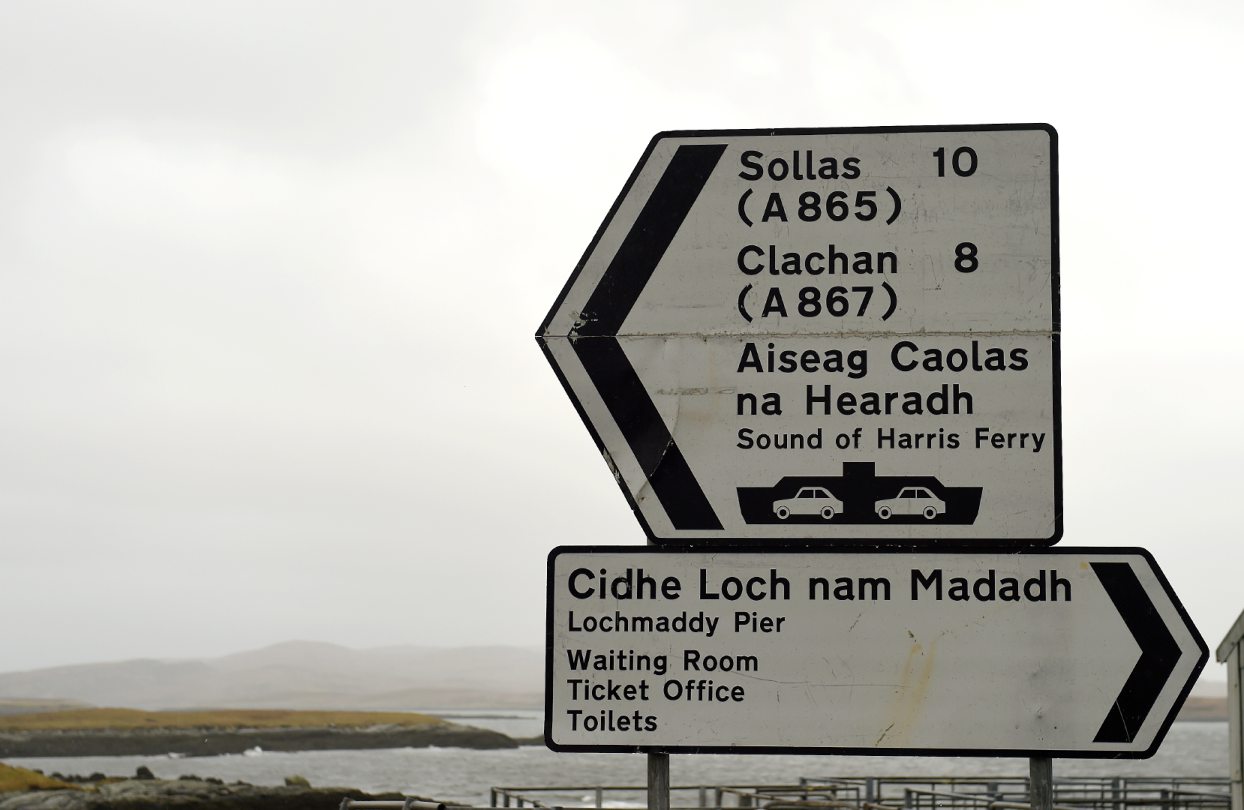

How much, for example, does that extra L in the English version of Malaig cost to write on all those road signs?

Or take Dùn Dè, where we Gaels do with five letters but, when it comes to the English language version, och, they have to add another letter – attaching an extra E at great cost, so that the budget increases dramatically when those poor signwriters have to carve out six letters, spelling Dundee. Jings, crivvens, help ma boab!

I jest, of course, because, in general, the original Gàidhlig names tend to be longer than the corrupted English ones, which have been cut through usage across the generations.

There are so many illustrations around Aberdeen itself, for example. Cùl Tìr (literally, “The Back of the Land”) becoming Culter through time. Coillte (Woods) becoming Cults. Baile Ghabhainn (Place of the Cattle-fold or Calves) becoming Balgownie…

Resentment of Gaelic is fear of the unknown

I realise why Gaelic is resented in some quarters. It’s mostly the fear of the unknown – what are these strange people talking about, and are they talking about me? The answer is: No – they’re (mostly) just getting on with their lives, debating which potatoes grow best on the machair. Kerr’s Pinks or Golden Wonders?

But it’s also partially a genuine bemusement (or horror) that any public money and time and resources are spent at all on what is perceived to be a dying language. Why bother with a few people here and there who all understand and speak English perfectly well anyway?

Good question. Though that may just be a sgadan-dearg – a kipper, or red herring. For language and communication are as complex and multilayered and as intricate and gorgeous as a Harris Tweed jacket.

Every language carries its own history and memories

Language is not a badge of allegiance, but a means of being. Far more than a matter of giving or receiving basic instructions.

I’m not sure my relationship with my wife would last that long if I just barked out requests now and again. Biadh! Uisge! Even if I stretched the request to two words. Mince, please. Or merely handed her the salt and grunted: “Salainn.”

Language is a creative marvel. It informs, entertains, connects, imagines, recalls, distracts, deludes, obfuscates

A more fulfilling relationship involves either asking for, or giving, the salt with a smile, and perhaps adding in a wee story of the Lewisman who claimed the sea was salty because John Murdo the salt merchant from Stornoway had, once upon a time, sailed across the Minch, smuggling salt in a creaky coracle, and was set upon by the savage MacLeods of Skye, and, to escape, ditched all the salt bags overboard.

This made the sea so salty that it attracted all the herring, which explains the remarkable growth of the Herring Industry in the 19th century.

In other words, language is a creative marvel. It informs, entertains, connects, imagines, recalls, distracts, deludes, obfuscates and all kinds of other adjectives (or is it verbs?). The thing is that every language carries its own history and memories and resonances and promises.

Which is why it’s always a delight to hear a Buchan loon speak; as he speaks, I see the ploughed landscapes of Aberdeenshire where I lived once upon a time, and, when I hear a good old-fashioned Inverness accent, I thank God that the global media has not (yet) completely abolished the indigenous. So with Gaelic.

Adding texture to the joy of life

Of course, we can all now speak this lovely language I’m writing in, but using Gàidhlig adds another texture to the joy of life. Like seeing a swan and not just a seagull on Loch Ness.

The marvel of human social value is worth more than any economic value. I suspect that Kwasi Kwarteng has wasted billions more of public money in the past few days than have ever been spent on Gàidhlig.

Gaelic brings the same as English and French and Italian and Chinese and all other languages to the table: uniqueness, diversity and riches. It’s like having a different meal.

We can sit every night and eat mince and tatties, but we can also vary it: fajitas on Monday, maybe, and salad on Tuesday, on to the fish supper on Friday. A varied and interesting diet, as opposed to the same old stew. Each language has its own blas (taste) and nourishment.

It’s like your garden: roses here and carrots there. A patch for the potatoes, and a bed for the herbs. Some for beauty, some for food. They can all flourish, given their own time and space.

English for starters, Gàidhlig for the main course and Doric fur pudding. Braw!

Angus Peter Campbell is an award-winning writer and actor from Uist

Conversation