The mixed emotions that affect so many of us at this time of year are captured by the story of The Snowman, writes Catherine Deveney.

Christmas memories. They swirl like snowflakes at this time of year, here and gone, fragile and delicate, melting on impact.

I am still at school. We are walking, the two of us, on a late November night, to the cafe round the corner for ice cream.

We are dressed in coats and scarves, the street lights soft-edged and ghostly through a freezing fog, our breath forming in puffy clouds. My arm is linked through his.

“Not long ’til Christmas,” my father says, because he knows, and I know, that Christmas is his favourite and mine, and the shared pleasure flows between us, lighting up the gloom like a strand of fairy lights. Trees and tinsel and tradition, but, above all, magic.

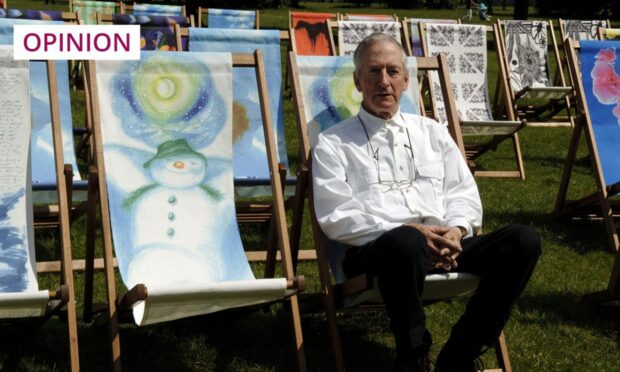

The bittersweet memories that affect so many of us at this time of year are captured by the story of The Snowman, so beautifully illustrated by Raymond Briggs, who died earlier this year.

The film was nominated for an Oscar when it was first released in 1982, and has become an iconic part of Christmas: on biscuit tins and wrapping paper, on baubles and napkins. Ironic, given that Briggs claimed to hate Christmas and created a grumpy, cartoon Father Christmas who grumbled his way through the Christmas Eve toy run.

“I don’t like the season at all and I make a point of grumping about it,” Briggs said, which perhaps explains the heartbreaking ending of the Snowman.

There is always magic

Who can forget the forlorn expression on the little boy’s face as he stands in the garden, trying to come to terms with his sense of loss? He has wakened full of anticipation of fresh adventures with his new friend, the snowman, only to discover one of life’s harshest truths: everything is transient; nothing lasts forever.

The snowman’s hat and scarf, are soggy, disappearing into a melting pile of slush. The snowman is gone, without a farewell, and without any promise or expectation of a return.

It would be tempting to describe it as a loss of innocence, the brutal awakening to the existential crisis we all face: what’s the point of anything if nothing lasts? And, yet, a colleague of Briggs, animator Roger Mainwood, suspected that Briggs’s “bah humbug” routine was mainly for comic effect. It seems likely.

The magic might eventually end in Briggs’s work, but it’s still there. Santa Claus does the Christmas Eve run, even if he complains; the snowman is still magically alive for a time, and capable of love and friendship, even if he ultimately melts into oblivion.

Better to have loved and lost

Raymond Briggs, an only child, was said to have been obsessed with his parents; a sense of loss that shaped his stories. “I don’t have happy endings,” he once said. “I create what seems natural and inevitable. The snowman melts, my parents died, animals die, flowers die. Everything does. There’s nothing particularly gloomy about it. It’s a fact of life.”

Better to have loved and lost, it is said, than never to have loved at all. In there is the key to the little boy’s predicament, and to that undercurrent of melancholy and nostalgia that so often runs through our Decembers. He hasn’t, after all, been left with nothing. He has memory. And so do we.

In memory, there is certainly sadness and loss, perhaps even a sense of abandonment, but there is also love and laughter and life-affirming experiences.

We each have our own secret sadnesses

Christmas is a strange time, when joy and sadness are juxtaposed in challenging ways. At this time of year, I always think of those who mourn, because grief becomes even sharper when surrounded by expectations of joy.

Every winter, the memories of that late November evening twinkle with my fairy lights, and I feel my dad’s presence

Every Christmas, we each have our own secret sadnesses. But joy is always possible. Memory is possible. And it makes me smile to think that Briggs, who told the world that everything was ephemeral, will be remembered each year for his creations. In his story, the snowman died – but, now, he lives.

“Raymond liked to act the professional curmudgeon,” his agent, Hilary Delamere, said when he died, “but we will remember him for his stories of love and of loss. I know from the many letters he received how his books and animations touched people’s hearts. He kept his curiosity and sense of wonder right up to the last.”

The cafe round the corner where my father and I bought ice cream is gone now, replaced with a motorway. My father, too, is gone. But, every winter, the memories of that late November evening twinkle with my fairy lights, and I feel his presence, his warmth, the comforting touch of his arm.

It is that piercing sadness of times gone by that Briggs captures so precisely in his work, and perhaps it is true that no joy is ever so unambiguous again as the joy of childhood. But it is also true that, at Christmas, we have the option to relight the past and carry it with us to the future.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter, and Scottish Newspaper Columnist of the Year 2022

Conversation