A lot of work is going into how the relationship between the Scottish and UK Governments might be improved, writes Chris Deerin.

The death of Tom Nairn at 90 robs Scotland of its most influential left-wing public intellectual of the past 50 years.

Since its publication in 1977, Nairn’s book, The Break-Up of Britain, has been the foundational work for a certain type of clever revolutionary who believes that the collapse of the country’s imperial power, coupled with the illogicality of its ragged constitution and the strong and often competing identities of its constituent parts, mean that the union is done for. Not a matter of if, only when.

Such was the power and persuasiveness of Nairn’s mind that, even today, there are young writers and academics who are unable to pen an article or paper that doesn’t reference his work and quote liberally from him. The style that was his is now theirs: disenchanted, unimpressed, sniffily superior and intimidatingly sure of itself.

To be fair, if you’re going to pick an idol, Nairn at least gripped a golden pen. His fine mind was matched by a talent for colourful readability – not a commonplace among political theorists.

Nairn is often praised for his optimism about what might follow the end of the UK and the birth of a separate Scottish state. But, depending on where you start from, he was also a nihilistic gloomster, whose vision of the end willed the means.

He saw no possibility of Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland continuing to operate as a unified, if loose, structure, or any point in trying to bring about that eventuality. Time may prove him right, of course, but there’s something deliberately defeatist, not to say wilfully ideological, in such an outlook.

People are trying to make the United Kingdom work

I spend a reasonable amount of time talking to people who are trying to make the United Kingdom work. Not just politicians, but civil servants who are dealing with the day-to-day functioning of the relationship between Westminster and the devolved institutions.

These are serious, intelligent, committed people, working through knotty problems that are often worsened by the political differences between the ruling administrations, and the willingness of their politicians to exploit difference for their own advantage.

Very sorry to hear that Tom Nairn has died. He was one of the greatest thinkers, political theorists and intellectuals that Scotland has ever produced – and certainly one of the leading and most respected voices of civic nationalism. My condolences to his loved ones. https://t.co/elTu51NeLS

— Nicola Sturgeon (@NicolaSturgeon) January 21, 2023

It’s a matter of great regret that mechanisms set up when devolution was created that were intended to manage these relations have failed to take root. This, I think, is mainly the fault of Whitehall, which early on adopted an attitude of “devolve and forget”. The result has been that, as Holyrood has latterly adopted a posture towards London that is an awkward mix of defensive crouch and lunging attack, the ability of the two to work through disputes has atrophied.

These days, it seems that the Supreme Court is effectively the first port of call to rule on differences of opinion, rather than the last

The pathways to mature and rational negotiation have become overgrown and weed-filled. It is clear, from a few decades’ distance, that more thought and energy should have been put into how the centre and the peripheries would work together in times of both harmony and disagreement.

These days, it seems that the Supreme Court is effectively the first port of call to rule on differences of opinion, rather than the last. This is both an expensive and confrontational way to do business.

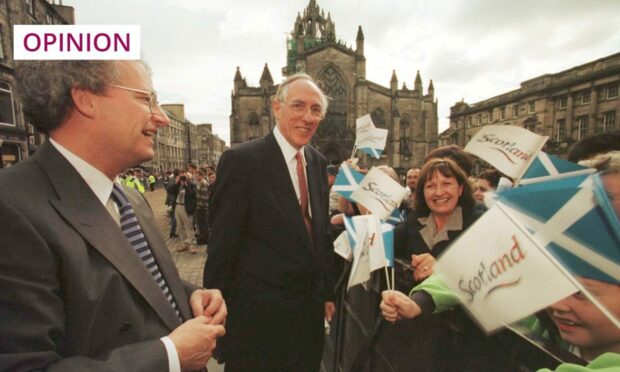

A lot of work is going into how this situation might be improved. There are big thoughts by ambitious thinkers like Gordon Brown. He wants to see a reordering of the entire structure of the UK, in an attempt to create a system that allows Britain’s identities and institutions to rub along more smoothly with one another.

This would be achieved through greater empowerment of regions, and new structures, where constructive debate might be had before, during and after contentious issues arise. Directly-elected mayors and a reconstituted House of Lords are examples of the solutions favoured by Brown.

Stability can be the bedrock of change

But there are also occasional examples of governments working well and positively behind the scenes, even if these receive less publicity than the high-profile clashes. One such case is the current negotiation taking place between London and Edinburgh over renewing the framework that governs the fiscal capacity of the Scottish Government.

I’m told discussions with SNP ministers are progressing well, with genuine buy-in from both sides

The first framework was agreed in 2016, following the cross-party Smith Commission that reached agreement on new powers for Holyrood, including enhanced powers over income tax and the benefits regime. That agreement stated that “the Scottish Government and the UK Government are committed to financial responsibility and democratic accountability, incentivising the Scottish Government to increase economic growth while allowing Scotland to contribute to the United Kingdom as a whole.”

It may be thought that this was more a matter of take than give for Nicola Sturgeon, as there has been a distinct absence of economic growth, or much effort to bring it about, since then. There are also major issues with the accountability of her administration, given the absence of a revising chamber at Holyrood and the weakness of the parliamentary committees.

But, with the fiscal framework currently being renegotiated, civil servants in London have certainly not given up on mannerly and mutually beneficial deal-making. There are open minds as to what might emerge – for example, Holyrood could be given capital borrowing powers, something Economy Secretary Kate Forbes has repeatedly called for. I’m told discussions with SNP ministers are progressing well, with genuine buy-in from both sides.

This might not be as sexy as a firecracker of a book that predicts dramatic decline and a thrilling endgame, but these hard yards ground out over dull days, months and years are, in the end, what allows a country to function. The young revolutionaries won’t like it, but stability can be the bedrock of change, too.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation