Attempts to tie national identity to a particular side of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill argument are deeply unhelpful, writes John Ferry.

Can we keep national flags, and, by extension, national identity out of the debate on reforming the gender recognition process?

In today’s Scotland, the answer is as predictable as it is depressing: of course we can’t.

Earlier this month, a protest against the introduction of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill was held outside the Holyrood parliament. Photos from the event show a number of protestors waving the Union Flag. The Saltire, meanwhile, has been present at protests in favour of the bill.

These attempts to tie national identity to a particular side of the argument are deeply unhelpful. They threaten to create further entrenchment and make reconciliation across an already bitter divide even more difficult.

Even if it involves a court clash between Scotland’s two layers of government, it should be possible for the legislative process to run its course without loading a national identity war on top of an already raging culture war.

The phrase “culture war” has been much in use lately.

It first became popular in the early 1990s, after the publication of the book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, by the academic James Davison Hunter.

As he said then, with words that seem more relevant today than ever: “On political matters, one can compromise; on matters of ultimate moral truth, one cannot. This is why the full range of issues today seems interminable.”

Politics played out as full-blown culture war creates uncompromising tribes and societies cut through with resentments.

Recently, Hunter has made the case that the financial crisis of 2008, and its resulting economic inequality, drove a wedge between the middle and working classes in America, so that class differences have been grafted onto cultural differences to create a new class-culture conflict. This division provided the perfect environment for Donald Trump to exploit resentments to the point of winning the presidency.

Is there a danger that, in Scotland, we create not a new class-culture conflict, but a national identity-culture conflict? The answer is yes, and this should be a red warning light for all who value healthy democracy.

A narrow focus on identity can stymie social and economic progress

Another American academic with something useful to add here is the political scientist Francis Fukuyama.

In his book, Identity, he argues that there is nothing wrong with identity politics as such, because it is a natural and inevitable response to injustice, but that it becomes problematic when identity is interpreted and asserted in certain, specific ways.

When we privilege opinions sincerely held over reasoned deliberation, we remove the space for people to abandon an opinion while maintaining their dignity

“Identity politics for some progressives has become a cheap substitute for serious thinking about how to reverse the 30-year trend in most liberal democracies toward greater socioeconomic inequality,” says Fukuyama.

A narrow focus on identity can stymie social and economic progress. It risks us missing the bigger picture, and prevents us even having reasonable discussion on the challenges we face.

The preoccupation with identity has clashed with the need for deliberative discourse, argues Fukuyama: “The focus on lived experience by identity groups valorises inner selves experienced emotionally rather than examined rationally.”

When we privilege opinions sincerely held over reasoned deliberation, we remove the space for people to abandon an opinion while maintaining their dignity. Under such circumstances, progress becomes much more difficult to achieve.

As the debate over gender recognition plays out, throwing national identity into the mix can only increase the chances of stopping progress.

Be wise to those looking to subsume your individuality

Some will argue that the constitutional ramifications of the UK Government using its Section 35 powers to halt the bill makes a clash of Scottish versus British identities inevitable.

This need not be the case, but we do have to recognise that some politicians now have a strong incentive to turn this debate into a fight between national identities.

Of course, Scottish politics over the last 10 years can, at least to some extent, be characterised as a deliberately provoked fight between national identities.

We will all have felt it: that finger poking you in the back, asking you to choose between being Scottish or British. Being both, or viewing national identity as something best left quietly sitting in the background, has, it has often seemed, not been an option.

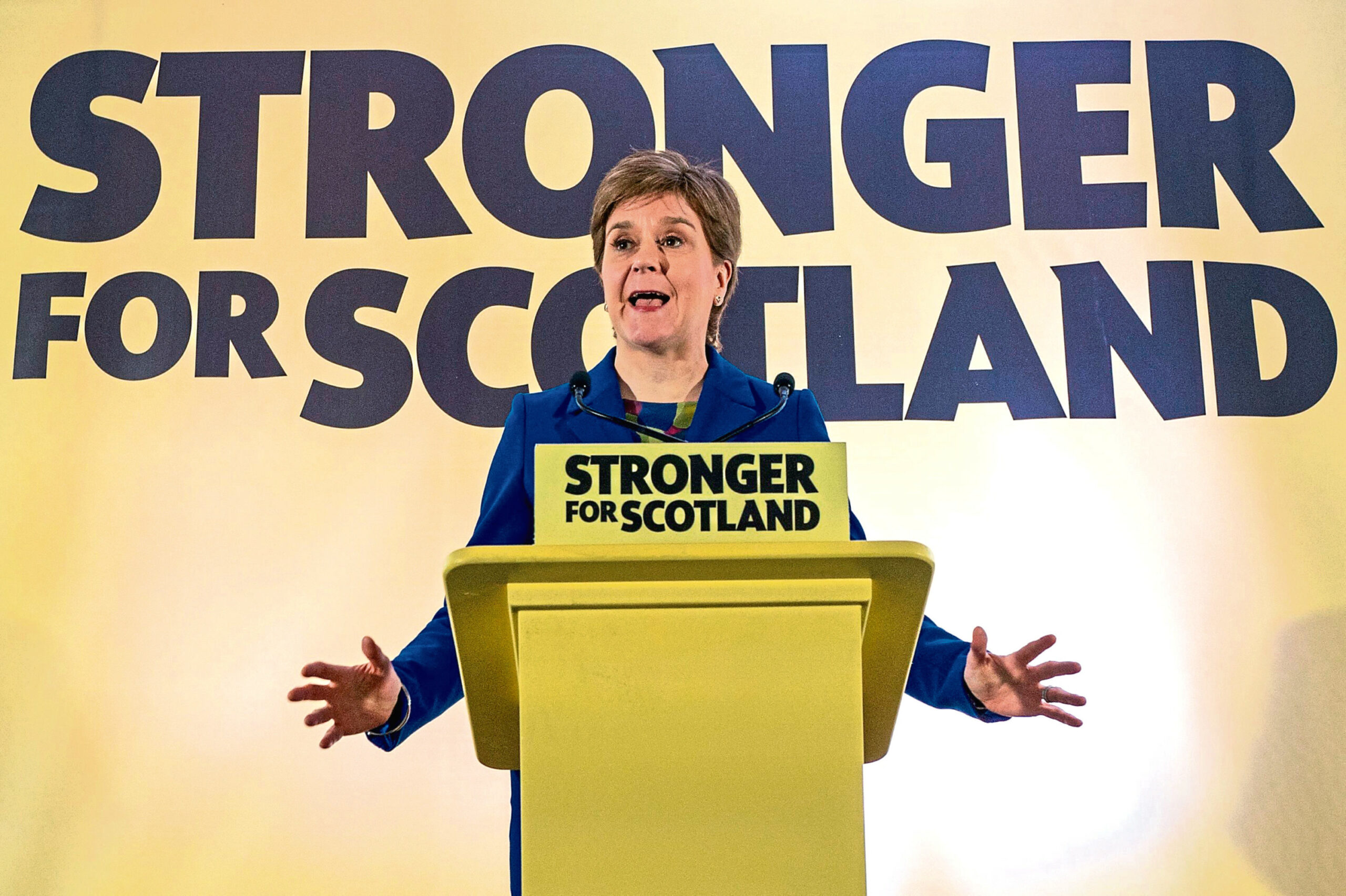

The SNP wants us to feel that there are Scottish values and British values, and that the former is clearly superior to the latter. To be good is to reject the British identity and to embrace, in its pure form, the Scottish.

This is the worst sort of politics, but it is, unfortunately, the politics we are dealing with today. The alternative is to be wise to those looking to subsume our individuality into a national identity fight.

That’s why we should keep national flags away from the debate over gender recognition. We must not let politicians with ulterior motives weaponise our national identities.

John Ferry is a regular commentator on Scottish politics and economics, a contributor to think tank These Islands, and finance spokesperson for the Scottish Liberal Democrats

Conversation