Levelling up isn’t the worst policy idea, but history proves it needs much more cash behind it in order to work, writes Jim Hunter.

Two chunks of UK Government cash came the north and north-east’s way last month.

First up was £26 million that’ll go into the Inverness and Cromarty Firth green freeport. Then came the area’s share of the latest round of so-called levelling up grants.

Shetland will get £27 million for a new ferry for Fair Isle, while Aberdeenshire is handed £20 million – split between a Peterhead “cultural quarter” centred on Arbuthnot House and a major expansion of Macduff’s marine aquarium.

These sums are not to be sneezed at and, despite the less than glittering record of the seven freeports Britain set up in the 1980s and, afterwards, phased out, hopes are especially high that the wider Highlands, as well as immediately affected localities, will benefit from what’s planned for Inverness and the Cromarty Firth.

But, to stand back a bit from the understandable welcome given to those January announcements is to be struck by the hopeless inadequacy of this country’s response to its crying need for a well organised and fully funded regional development strategy.

Grants awarded under the levelling up heading in January added up to £2.1 billion nationwide. This expenditure, divvied up among 111 successful applicants, was hailed by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak as “transformational”. But is it really?

Germany holds the answer

Given the extent of regional inequalities across the UK – where disparities between wealthier and poorer areas are greater than almost anywhere else in the developed world – that £2.1 billion, irrespective of what it might accomplish in the places where it’s spent, is unlikely to produce any very measurable change in the wider picture.

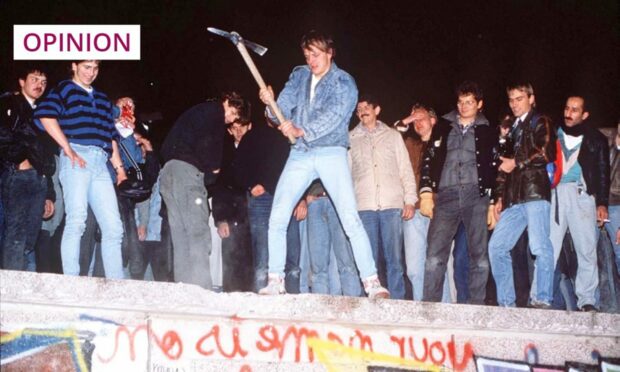

That would take spending on an altogether vaster scale. Just how much vaster can be seen from what it has cost Germany to tackle the economic and other imbalances its government confronted when, in 1990, the Berlin Wall came down and the former West and East Germanies became one.

The German example, as it happens, was highlighted by then Prime Minister Boris Johnson when, in July 2021, he set out the case for the policy that’s resulted in those 111 levelling up grants. He’d visited East Germany in 1990, said Mr Johnson, and he’d “been amazed at how far behind West Germany it then was”.

Paying tribute to what’s since been done to eliminate that divergence, Boris Johnson went on to say that “to a large extent Germany has succeeded in levelling up where we have not”.

This, he stressed, was why, per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – a standard measure of a nation or region’s success – is lower in many parts of today’s Britain than it was in East Germany just after the collapse of the east’s communist regime. Hence the UK’s urgent need, Mr Johnson contended, for a levelling up programme on a par with the German one.

It’s hard to argue with that policy prescription. But, it’s still harder to contend that what’s now being delivered comes anywhere close to what’s required, if people in the UK’s more disadvantaged regions are to enjoy living standards and employment opportunities on a par with those available to folk in the country’s more prosperous places.

£2.1 billion is nowhere near enough

A well-worked-out approach to regional development wouldn’t depend, as levelling up does, on getting financially hard-pressed local authorities to spend lots of money; £325,000 in Moray Council’s case, on aid bids – most of which, as with Moray’s, are then rejected by government.

The German development programme that Boris Johnson spoke about so glowingly – the programme the UK Government’s levelling up strategy was supposed to emulate – cost more than 30 times that sum every year for a quarter of a century

Nor would it result in the biggest slice of levelling up cash going, as happened in January, to what’s by every measure the UK’s richest region, London and south-east England – where, for instance, £45 million (nearly as much as Shetland and Aberdeenshire are getting between them) will be spent in Dover on border control points and other infrastructure made necessary by Brexit.

But, the most glaring weakness of levelling up as presently pursued can be traced to the UK Government’s point-blank refusal, in this as in so many other areas of policy, from health to education, to spend anything like the amount of money needed to tackle problems rooted in decades of underinvestment and neglect.

The £2.1 billion going to the 111 levelling up projects that have just been given the go-ahead might sound like a lot of money. And it is a lot of money.

But, the German development programme that Boris Johnson spoke about so glowingly – the programme the UK Government’s levelling up strategy was supposed to emulate – cost more than 30 times that sum every year for a quarter of a century.

These are resources of the sort you have to find if you’re serious about removing regional inequalities of the kind blighting Britain. But, with more and more Tory MPs and their press backers again obsessing about tax cuts, and with Labour unwilling to commit to worthwhile spending increases, no such resources are likely to be forthcoming.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands

Conversation