Film screenings are selling out in unexpected places, and it proves the power of both cinema and community, writes Colin Farquhar.

Even during a mild February, Braemar Village Hall is a little chilly. You can’t quite see your breath, but you might imagine that it isn’t too far off.

The 7pm drive to get there is mostly dark at this time of year, stars appearing more frequently the further into the Cairngorms you go; the shadows and dark lines of the hills against the dark blue, and then black, sky.

There is a cinema screen hung against the east wall of the hall. A projector is overhead, above a short row of chairs, which are neatly arranged in a line. Three other people appear. We sit down and politely say “hullo”.

A woman comes in and gives each audience member, now numbering eight, a small cup of salted popcorn. We’ve come here tonight to watch Carol Reed’s The Third Man, a film which is now, having been released in 1949, the best part of a century old.

It might be a long trek to come out to the deepest, darkest reaches of Aberdeenshire on a Friday night to watch a film, but I love The Third Man and I love Braemar. Always having lived by the coast, I think I hold a certain fascination for landlocked towns, especially ones this far into the hills. Braemar feels like it exists beyond the edge of the world, always just slightly further along the road than you think.

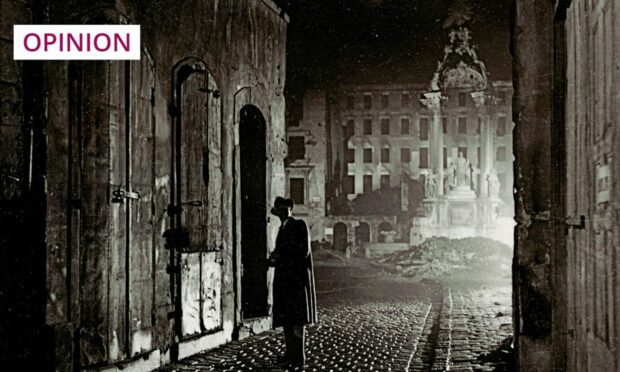

In The Third Man, Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, proves just as elusive, dashing down Vienna’s cobbled streets, chased most closely by his own shadow. If you’ve ever seen it, you’ll probably remember two things in particular – one is the music; the other is Harry’s beaming, broad and cheeky smile as he finally appears, illuminated in a doorway, looking up at the camera with a slight shake of the head.

The film is showing because the folk behind The Fife Arms, the rather majestic and newly refurbished hotel in Braemar, have begun a programme of screenings through February, shown in the local community.

They’ve started with three British-produced films to align with the Baftas, celebrating “extraordinary creativity in our extraordinary location”. The first film was Four Weddings and a Funeral. This is the second.

They do still make them like The Third Man

The man sitting next to us leans over to another in his party and whispers: “They don’t make them like this anymore”, as the protagonists of the film descend into the sewers of Vienna to chase Harry. The long tunnels and waterfalls that run away toward the blue Danube, under the crumbling, post-war, Austrian city.

But they DO still make them like this, I think. The angles, the shadows, the dark corridors; the quick cuts that have just gotten quicker over time, and the shadowy bad guys, kept off screen until the vital moment, spoken of in hushed tones and whispers. They’re all still here, nearly 100 years later, in so many TV shows, video games and films.

This coming weekend, they’ll be showing Shakespeare in Love, with an in-person Q&A with Simon Callow, who plays Edmund Tilney in the film. I ask tonight’s projectionist pre-film how many tickets are sold for that and he says it’s “much busier”, and is almost sold out, Simon Callow proving quite the draw. I wonder how many folk can fit into the hall.

You may have read that The Fife Arms proudly displays a Picasso in its lobby bar. It does. It’s in the room at the end, just past the Lucian Freud, which hangs above an extravagant sofa.

Community cinemas are keeping hope alive

Judi Dench was there at New Year, playing piano with Sharleen Spiteri, bringing some Hollywood glamour even before the film programme began. Weirdly, it sounds like something that might happen in downtown Vienna, not a sleepy Scottish town in the Cairngorms – a movie star and a pop star, tinkling the ivories together, belting out Waterloo.

And, during Shakespeare in Love, Judi will reappear at the village hall – on the cinema screen, at least – having a best supporting actress award-winning role in the film. Famously, and then slightly controversially, triumphant, after only around eight minutes on screen. Coincidentally, it’s about the same length of time that Orson Welles, as Harry Lime, appears in The Third Man.

Before I leave, I look around and think that Simon Callow will stand, or sit, in this very place in only seven days time, in a sold out hall

Our film ends with a funeral. Harry Lime has, or perhaps hasn’t, been shot off screen, and the protagonist stays behind in Vienna for the girl, who, in the final scene, walks past him and beyond the camera. The credits roll, the projectionist turns on the lights, and everyone says bye, and thank you, to one another.

Before I leave, I look around and think that Simon Callow will stand, or sit, in this very place in only seven days time, in a sold out hall. Community cinemas in Aberdeen, both city and Shire, are keeping cinema alive, even if it’s sometimes slightly elusive. Extraordinary cinema, in extraordinary times.

Colin Farquhar is former head of cinema operations for Belmont Filmhouse in Aberdeen

Conversation