As the first minister prepares to step down, her party finds itself more divided than ever and at a loss for a new leader, writes David Knight.

I was just putting the finishing touches to my column when the news broke about Nicola Sturgeon quitting.

It could turn out to be one of those memorable historical moments for many, who will always recall what they were doing at that precise moment. For me, it was having a coffee in Morrisons supermarket, Aberdeen, to be precise – taking a breather after a fruitless search for a jar of Baxters shredded beetroot.

These are the everyday trials and tribulations facing ordinary people, of which Sturgeon was accused of losing track as she chased ideological dreams with controversial gender recognition reform and a “de facto” independence referendum.

But she was well and truly shredded by these crises as she limped towards the exit door in recent months.

They say all political careers end in failure, and significant how it’s happened again to the supposedly invincible first minister – if judged by the be-all and end-all of delivering independence. Having said that, many critics claim her achievements on key political issues generally were pretty dismal.

But it’s also an inescapable “de facto” fact of political life that a 10-year run is the best a lucky leader can ever hope to achieve. Sturgeon was into the final furlong by that measure, but a bone-crunching poll a week ago revealed almost 50% wanted her to quit now.

And there was open rebellion in her own ranks over hopelessly flawed gender recognition reform and her shambolic plan to hijack the next general election in Scotland, while passing it off as indyref2. The latter being a juxtaposition so extraordinarily ill-judged and surreal that I had described it as like trying to pass off sea bass as a loaf of bread.

For me, there was something deeply worrying about a political leader trying to subvert the democratic process for her own ends.

Filling Sturgeon’s shoes is a monumental challenge

It looked like Sturgeon had been wrestling with her exit for some time. Maybe that was because the dial was consistently stuck in more or less the same weak place when measuring support for independence – under 50% for more than a decade, stretching all the way back to the years before the 2014 referendum, when her mentor-turned-nemesis Alex Salmond launched the longest conversation of all time.

Gender recognition reform triggered party rebellion and crushing condemnation from Salmond, who accused Sturgeon of putting the independence cause back years.

So, it’s been the long goodbye for her. Something like the lyric from Bruce Springsteen’s song Long Goodbye: “I guess I been packin’ kinda slow”.

In the original column I was writing, before being interrupted by Sturgeon’s resignation, I asked a rhetorical question about whether the wheels were coming off her leadership wagon. I answered with: “I’m not sure, but I think the nuts and bolts holding them in place are looser.”

Little did I know that things were moving faster than I anticipated.

Her leadership became a political car crash, her potential successors scattered about on the roadside – with about the same level of charisma as flattened traffic cones.

Sturgeon was anointed as the chosen one after Salmond’s fall, as his obvious successor. That person does not exist anymore; we just have the tired old familiar faces, or those with precious little experience.

Filling her shoes is a monumental challenge, as the SNP stands bewildered and lost at a dark, chilly crossroads.

What will the SNP’s tactics be now?

Is it more of the same to come – in Sturgeon and Salmond’s combative, abrasive image But this hasn’t worked, has it?

So, a completely new conciliatory, nicey-nicey change of direction to win the hearts of the doubters?

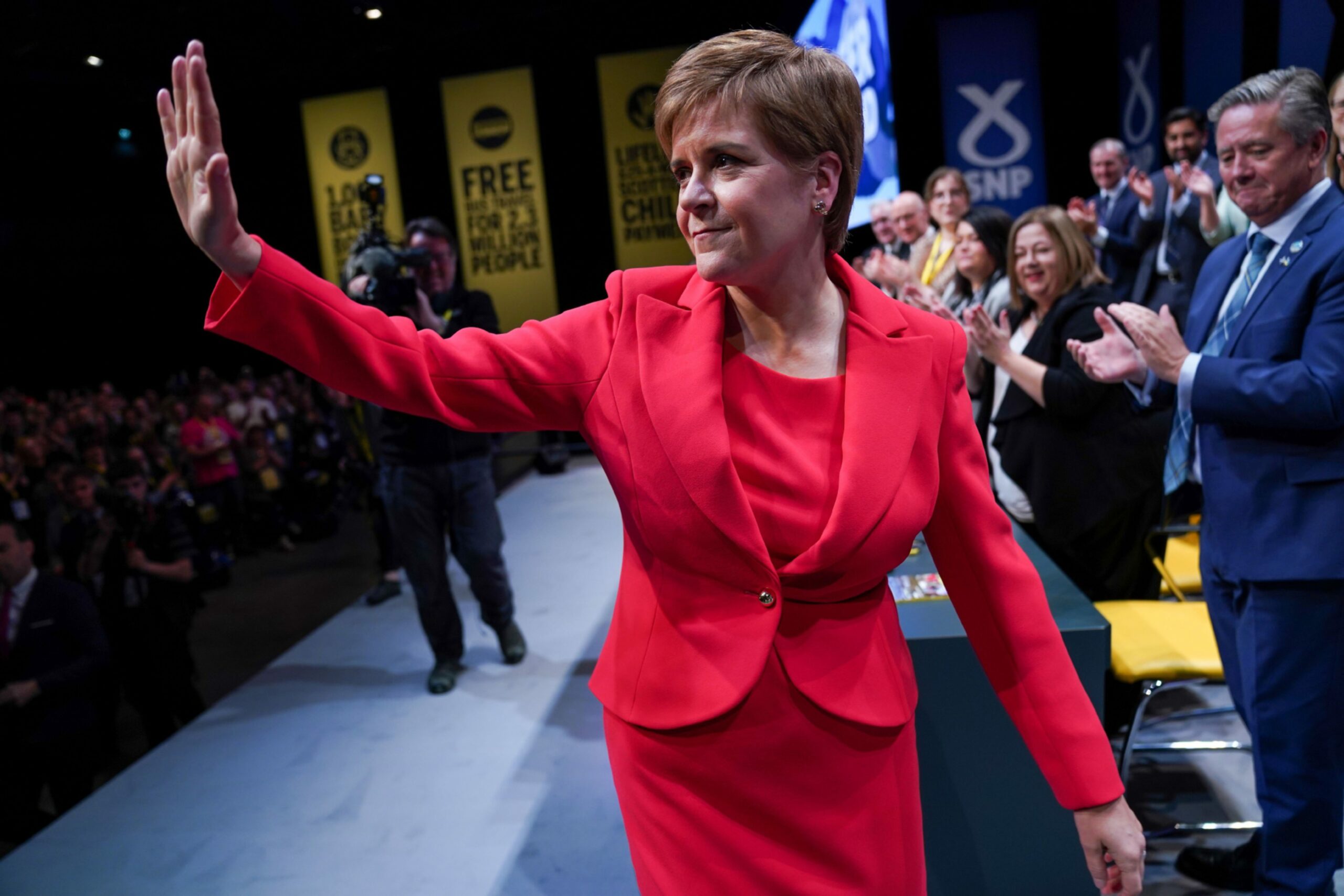

Sturgeon was a political giant in Scotland; feeble opponents were unable to land a glove on her until she became trapped on the ropes

SNP MP Stewart McDonald possibly hinted at something like this when he bluntly dismissed Sturgeon’s de facto referendum proposals as “deficient” and unachievable. He spoke of the need to build significant majority support over a sustained period to justify another referendum.

But that will hardly satisfy the hardcore separatists, the “when do we want it? We want it now!” brigade.

The problem is that the Nos and Don’t Knows fear the constant shouting and militaristic rhetoric.

Mussolini said that if you can sell the dream, people will climb a mountain for you. But, with Salmond and Sturgeon, many people felt they were being asked to walk up Referendum Hill in a blindfold and jump off a cliff.

Despite self-inflicted injuries over her judgment latterly, Sturgeon was a political giant in Scotland; feeble opponents were unable to land a glove on her until she became trapped on the ropes.

As she quit, people in Scotland fell into two camps. The committed diehards were gutted, the majority had a smile on their faces and a new spring in their step.

As a new era dawns, I am wondering about a fundamental flaw within the party. Could it be that the trouble with the SNP is it’s too scary for its own good?

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal

Conversation