Erasing problematic references from literature will not erase problems in our society, writes Catherine Deveney.

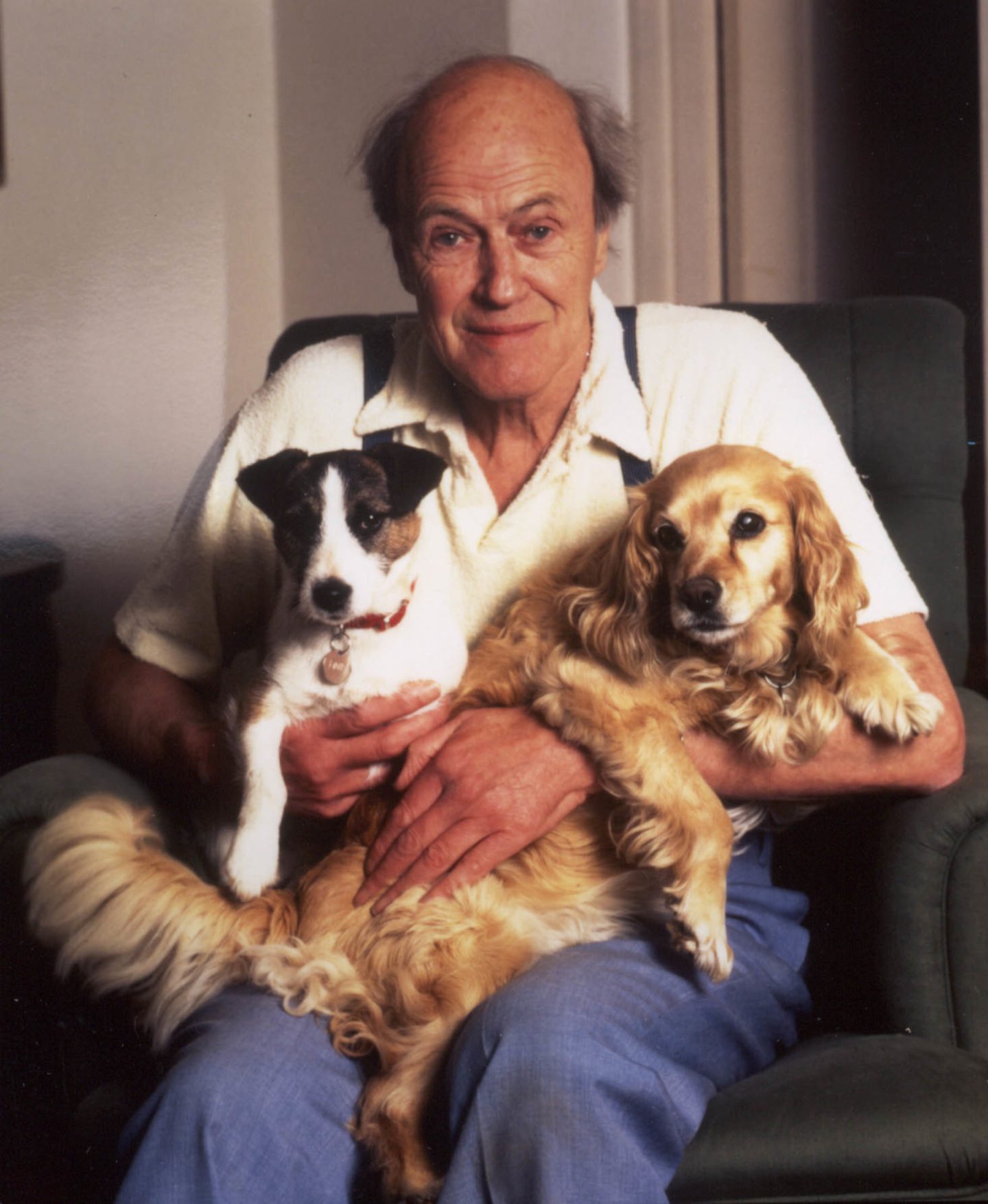

What does it say about our world that it is – according to “sensitivity readers” – perfectly acceptable for the late children’s author Roald Dahl to call a character “beastly” but not “ugly”?

Ugly-on-the-outside is obviously far more shaming than ugly-on-the-inside, even, apparently, for animals. Dahl’s “fat little brown mouse” was changed to “little brown mouse”, for fear of causing offence, presumably to fat rodents.

The western world may be struggling with double-cheeseburger-chips-and-milkshake induced obesity, weight-related diabetes and strokes, but God forbid we call a fat mouse a fat mouse. Or, for that matter, a piece of irrational, verbal vandalism censorship.

We have become a nation of ostriches. Heads in the sand, backsides in the air, can’t see it so it doesn’t exist. If we erase it, it never happened! Fingers in the ears… la, la, la. Until, suddenly, we jolt out heads out of the sand and shout random concepts, as if knowing the words solves the problem. Racism! Fat-ism! Sexism! Antisemitism! Mouse-ism! What?

Oh, that we actually tackled the issues instead of being professionally offended by them. After last week’s Dahl furore, this week we had the insensitivity readers tampering with James Bond.

They removed “potentially racist comments”, while inexplicably leaving references to the “sweet tang of rape”, “blithering women” failing to do “a man’s work”, and homosexuality being a “stubborn disability”.

Offensive? Certainly – just as Dahl sometimes is. But, if we had writings from the Middle Ages, we would not censor out the bits we didn’t like for a modern audience. What about protecting history?

The illustration of the wrong path is not an invitation to walk it

All writing should be seen in the context of its time. The way we’re going, Shakespeare will be banned for his antisemitic creation of Shylock; Dickens for working-class tourism in his depiction of the Cratchit family, and for body shaming “the fat boy” in The Pickwick Papers; and George Eliot for cultural appropriation because, actually, “he” was a “she”, and therefore had no business whatsoever assuming a world view that wasn’t his to own. Hers to own.

Ooh, no, wait a minute, could this now be viewed as both sexist and prejudiced against non-binary identities? Let’s decide later how offended we are by THAT one.

Erasing references does not erase problems. If we ban Billy Bunter, will no child ever be fat again?

I’m a feminist. I can, therefore, choose to ignore 1950s James Bond. But, if I read it, I don’t expect him to talk like a millennial who has been on a gender awareness course and sports a Harry Styles-inspired pearl necklace.

If we ban characters from speaking in ways of which we fundamentally disapprove, those views will still exist in our communities. Fiction is a mirror to our society, not the creator of it.

For children, the illustration of the wrong path is not an invitation to walk it; on the contrary, it can highlight the right path. Does the very existence of cruel characters not enable us to discuss their unattractive qualities?

Isn’t it time we left the choice to readers?

I had an interesting example of this recently, during an advanced adult creative writing class in which participants were asked to write in a voice other than their own. In preparation, we used historical voices from the Holocaust as research. The resulting exercise was designed to challenge: the class were asked to adopt the voice of a Gestapo officer.

Here’s what happened. In a lively debate about cultural appropriation, we discussed the current trend to “cancel” any writing seen as politically incorrect. There was, as you might expect amongst people interested in writing, a fairly unified view about the detrimental effects on creativity. But, when it came to the Gestapo voice, not everyone could face the exercise.

Of those who did, the results divided into two. Some tried to “humanise” the Gestapo voice because they were scared of being seen as antisemitic. Their characterisation slipped, and the Gestapo man became partly them – and that tempering of his character became dangerously apologetic.

Isn’t that, after all, both the thrill and the skill of writing: to convince you of the authenticity of characters who are not the writer themselves?

Those who did not ameliorate his evil intent produced the most powerful writing. Why? Because their Gestapo man was coldly, chillingly, realistic. It was the uncensored evil that highlighted his abhorrent nature most powerfully. Isn’t that, after all, both the thrill and the skill of writing: to convince you of the authenticity of characters who are not the writer themselves?

One piece stunned everyone into silence. Given just the words, class members thought it had been written by a man. “I felt dirty after writing it,” the female author said. But, far from being antisemitic, her piece could have been used in Holocaust education.

Writing is powerful. Unless it is promulgating illegality, isn’t it time we left the choice to readers? Nobody is forcing them to read “offensive” material.

Let writers’ words do the talking, not sensitivity readers who, as far as I can see, have an inconsistent, irrational and inappropriate understanding of both the power and the purpose of fiction.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter, and Scottish Newspaper Columnist of the Year 2022

Conversation