For many years, I have had a recurring dream.

In it, I approach the white wall that marks the entrance off the main road to Annfield Stadium, for five decades the home of Stirling Albion Football Club. I walk into the ground and wander around the silent, empty terraces, before ending up on the pitch, looking towards the clubhouse above the dugouts. Then I leave again. Dream ends.

It is a piece of subconscious nostalgia. Annfield was closed in 1993, then demolished and replaced by a development of flats. Today, the Albion play at Forthbank, on the outskirts of town.

I grew up in Stirling and, for a few years in the mid-1980s, was a regular at Annfield, which was only a short walk from our house. I must have been 11 or 12, and would head there with a friend or two every other Saturday.

It was a blissful lower-league experience – the terracing was just one big, open circle, and the home and away fans would swap ends at half-time. It felt safe and friendly.

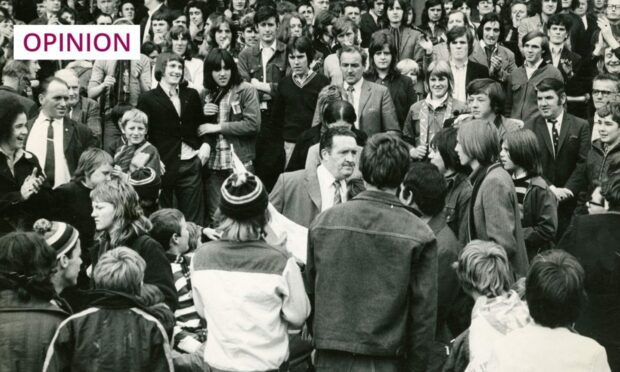

When we could get away with it, we would sneak into the clubhouse after the game, where we could watch the players scoop a few post-match pints. A deathless highlight came when, my face by now familiar, the manager, Alex Smith – who would go on to bigger things with Aberdeen and St Mirren – patted me on the head and called me “the Albion’s greatest fan”. Not true, but I glowed with pride.

We would go to occasional away games, too, on the fans’ bus, up to Brechin or Arbroath, where we were looked after by the older guys. It was a fine, good-humoured community of people, who took real pleasure in their weekly devotion, even if there wasn’t much at stake; the football wasn’t always the silkiest and the results were often disappointing.

A party atmosphere, no matter the league

I don’t get to many football matches these days, but by chance recently found myself at two from very different ends of the scale. The first was Manchester United versus Barcelona where, on an unusually sultry evening, 72,000 fans created an atmosphere of giddy euphoria as some of the best players in the world battled each other with superlative skill and grit. It was a magical experience of the Manc spirit, as Old Trafford lived up to its Theatre of Dreams nickname.

The second was a return to the club of my childhood. One of my friends from those Annfield days called to say that Stirling Albion were playing Dumbarton in a “top of the table clash”. This was news to me, but apparently the Albion had been having a great season and might be promoted to League One. Dumbarton being their main rivals, this match could be decisive.

Saturday came, and we joined an impressively long queue for the Forthbank turnstiles. My friend brought his dad, who I hadn’t seen since my late teens, and who is now 85.

👏 Our fans pic.twitter.com/2bwLIsdlL7

— Stirling Albion FC (@Stirling_Albion) April 16, 2023

There were many more old fellows, younger dads, teenagers and kids, and a fair few mums, too. The attendance was 1,441 – about double the usual home crowd. The pie and Bovril stall was completely overwhelmed at half-time.

It wasn’t Old Trafford, obviously, but it was noisy and felt a bit like a party. A group of fans hoisted a red banner, while someone else had a drum, which briefly threatened to give things a Latin air… And was that a chorus of vuvuzelas?

The football was much better than I had expected. Not to overstate it, but Pep Guardiola’s triangles and patient passing have clearly made an impact on Scotland’s lower leagues.

The team’s creative midfielder – he had long hair, so you knew that’s what he was – had a nice touch, and sashayed his arms and hips around in a way that can only be described as Xavi-esque. The left-winger was excitingly rampant, and the little centre-forward battled gamely against Dumbarton’s giant defenders. The game ended 2-2, the promotion dream remained alive, and the fans departed relatively content.

A town lacking in identity

I return again to that word “community”. Stirling – my home again after many years away – is a curious place. It is properly ancient and scenic, with its castle and the site of the Battle of Bannockburn and the National Wallace Monument. The Ochils loom like hefty shoulders in a sodden raincoat, and the River Forth twists gently through.

And, yet, the town – it is now officially a city but doesn’t feel like one – lacks much sense of its own identity. It’s a great place to live and raise children, but I’m not even sure what the word is for locals like me: a Stirlingian? A Stirlingonian? A Stirlinger? Ugh.

For many residents, Stirling is a commuter town for Glasgow and Edinburgh, both of which are a short drive or train journey away. Its school pupils tend to support Celtic or Rangers, much as they did in my day – hence, Stirling Albion’s crowds rarely rise above the hundreds. The dilapidated centre has never lived up to the glamour of its historical surroundings.

There are plans for a National Tartan Centre, and for a new, regular train service to London, both of which would be welcome. But how do you create heart and belonging in a place that seems stubbornly resistant to acquiring either?

In other words, how do you translate the spirit of those Albion fans on to a broader canvas? As I turn 50 this year, the challenge remains sadly unmet.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation