“I’m so lucky that I’m half Urdu and half English, aren’t I, mummy?”

My heart skips a beat, and I catch my breath. Sometimes these little people can be so wise beyond their years.

OK, Maya might have got herself a tiny bit muddled and put it clumsily – by Urdu, she means her Pakistani heritage from her dad’s side – but you get the gist.

And – even if, perhaps, it has more to do with Easter and Eid coming in quick succession this year and all those extra presents – my five-year-old’s realisation about the benefits of growing up within two cultures strikes a chord with me.

Because, from the outset, Mr R and I have made a conscious effort to expose her and her younger brother, Kamran, to both sets of customs; to encourage them to be proud of the different strands of their background that have intertwined – indeed, still are meshing together – to create our wonderful family.

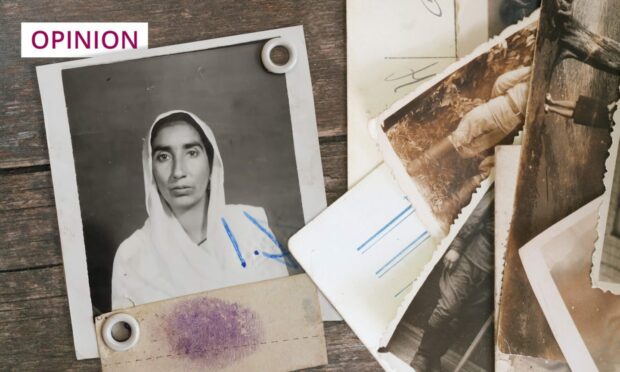

I was reminded powerfully this week of the importance of this, when my husband’s auntie shared a special photo with us – a black and white picture of her mother’s passport from when she first came to the UK in 1966. It’s such an arresting image, and I’ve not been able to stop looking at it.

I only ever knew Rehmat, or Mam, as everyone called her, in her twilight years, so to see her in her prime – several years younger than I am now – was quite something.

I immediately noticed her beauty, which shouldn’t really have come as a surprise, as she was attractive to the very end. But it’s the story behind the photo – the sequence of events that led to her departure for England – that makes it so engaging.

I’ve since learned that she and Fateh, Mr R’s grandfather, both born in Punjab, India, crossed the newly delineated border into Pakistan during the partition in 1947, before ultimately deciding to try to carve out a new life halfway across the world. She lost three brothers, among other family members, in the process, like so many.

“My dad came to the UK in 1958, when I was only a few months old,” my auntie-in-law told me when I asked about her parents.

“I didn’t see him until I was seven, when he returned for a visit. We later joined him.

“I have so much admiration and love for my parents, for their courage and bravery, for the trials they faced – they remained so optimistic.

“I feel so privileged to have had the time and communication with them to know so much about their childhood, their relationship with each other, and stories about incidents and people that shaped them.”

I want my children to enjoy a connection to their roots

She’s absolutely right, and I too feel honoured (a responsibility even, especially as a white mother of mixed children) to help hand down this history in turn, alongside the catalogue of anecdotes I can and do impart about my own Aberdonian and Cockney ancestry – whether it be my mum’s parents’ experiences in World War Two, or decades of public service as councillors and involvement in the early Labour movement on my dad’s side.

My life has been deeply enriched by learning about and spending time with those whose footprints we now follow, and I want my children to enjoy a similar connection to their roots.

Quite understandably, parents raising offspring in an entirely new setting away from their homeland often strive to maintain a link by passing on cultural and religious practices. This shouldn’t simply be an exercise in preservation, however, born of nostalgia for a golden age we can’t know existed – far from it.

Thanks to the determination of Mr R’s grandparents, thanks to their willingness to take a chance, his auntie’s life, spent in the north-east of England, has panned out very differently to theirs – as has my husband’s. Our children’s experiences will be still further removed – and that’s fine.

Our family’s journey carries on

Inevitably, with every generation that passes, traditions and memories fall by the wayside as circumstances change. Nothing lasts forever; most of us will eventually be forgotten.

As 18th century poet William Cowper wrote: “We turn to dust, and all our mightiest works die too: the deep foundations that we lay, time ploughs them up, and not a trace remains.”

I’m not talking about futile attempts to keep things the same, but rather building on the endeavours of the people who brought us to this point

I’m not talking about futile attempts to keep things the same, but rather building on the endeavours of the people who brought us to this point. Because, if we are taught about the individual pieces that make us up – if we learn to appreciate their value – we will be able to grow into more than the sum of our parts, and work out who we can and want to be.

As Maya and Kamran begin to take the helm, I look forward to watching them pursue their chosen paths and move our family’s journey on.

Lindsay Razaq is a journalist and former P&J Westminster political correspondent who now combines freelance writing with being a mum

Conversation