I felt elated as I left Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, for two very good reasons.

The first was that nurses told me I could switch to annual blood tests to check if I am still OK after my big operation almost five years ago.

A lot of this follow-up work was skewered by Covid, but the specialist unit I attend maintained remote contact through thick and thin. Even though some of them were drafted temporarily into frontline trenches to fight Covid in intensive care units.

I always appreciated this; I wasn’t alone or forgotten as the NHS cleared the decks like a battleship going into action.

Now, we are face to face again at the hospital, which is always better, I feel.

It used to be three-month checks, which simultaneously gave me a sense of reassurance and dread. Glad I was being checked every 12 weeks, but frightened it would come back.

I’m not out of the woods, as I still struggle with side effects. But, at this juncture, I feel compelled to trot out that old chestnut: there are a lot worse off than me.

I’m lucky, as many have died while I’m currently still here – thanks to being caught early. Otherwise, I’d be gone by now.

I could faintly hear a nurse on the other side of the unit running through the same big operation with another gentleman who had popped in for an informal chat before his big day. It all came flashing back, after my two and a half hours on the operating table.

Not surprisingly, he looked a bit apprehensive. So, when the nurse disappeared for a few minutes, I struck up a conversation and tried to reassure him; I hope it helped.

He was “lucky” in the sense that he had obvious symptoms. I had none – it was discovered by a combination of pure luck and a GP called Wendy who had a hunch that something needed checking further.

I’ll trot out something else you’ve heard before, but I can’t say often enough – get yourself checked early. I know some people might be stifling a yawn, but it’s true.

Cancer reminds me of the western film, The Quick and the Dead – check yourself quick or you might end up dead. Don’t give up at the first hurdle because you think waiting lists are too long.

Little things matter, but there is a time and place

The other reason I felt elated heading towards the exit was that I discovered you can buy individual doughnuts in a little bakery in the hospital M&S store. Trivial stuff, eh?

But, little things matter at times like this; their importance becomes magnified way above their humdrum status.

Supermarket doughnuts in packs of five, which the two of us can’t polish off, are the bane of my life. Shall I start coming here for them instead?

No, I’d feel guilty clogging up a space in the Lady Helen Wood car park just to buy doughnuts.

Yes, little things matter, but there is a time and place. For example, I had a little altercation in the hospital cafe about milk in my Americano instead of on the side: I should have asked in the first place, they argued with some justification.

It was getting tense, so I glanced sideways to gauge any unrest in the queue.

A woman in a wheelchair with the stump of her amputated leg on display, another with face injuries that looked like she’d fallen down the stairs. What on earth was I playing at? This isn’t The Savoy, you prima donna.

Don’t cross such a dangerous line

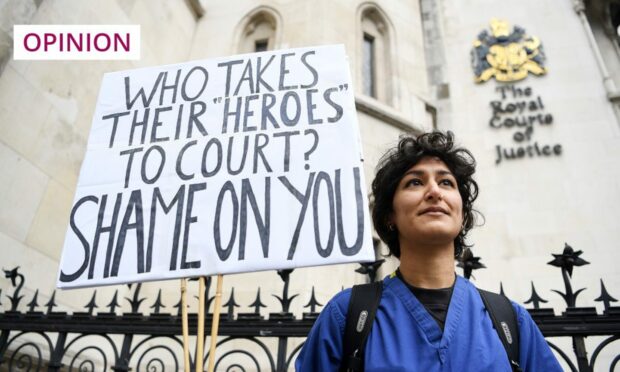

I support our nurses and junior doctors – they deserve every penny that’s fair and reasonable, but they are not beyond reproach. Especially in England, after a nuclear-button strike ultimatum to abandon those most at risk on emergency and cancer wards.

They must heed an oblique warning by Huw Pill, chief economist at the Bank of England, that they were feeding inflation with excessive demands.

Common sense restored the calm here in Scotland, but many of us worry about sick relatives down south. The Royal College of Nursing is pressing on in England, even although many health colleagues in other unions have accepted pay offers.

I see young, smiling medics in news reports, waving placards, reminiscent of fresh-faced students demanding statues be toppled. But this is life or death

A few days after my hospital visit, I found myself speaking with a senior nurse in Birmingham about my mother-in-law, who was whisked in as an emergency case. I welled up with gratitude as she explained everything they had done for her.

Later, I could have cried in frustration when they called to tell me they had just delivered her home at midnight – she’s almost 91, for pity’s sake.

But I dread to think what fate would have befallen her had they been on strike.

I see young, smiling medics in news reports, waving placards, reminiscent of fresh-faced students demanding statues be toppled. But this is life or death.

I love our nurses and doctors, but don’t cross such a dangerous line. This isn’t Russian roulette.

I urge both sides to end this dispute – please don’t be doughnuts.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal

Conversation