It’s pretty obvious that actor Johnny Depp’s celebrity portraits are rubbish, because you know instantly who they are meant to be.

Not a good thing in the complex art world, which prefers a little mystery: an unmade bed, a pickled shark, a Turner Prize-winning video that makes you think what the heck?

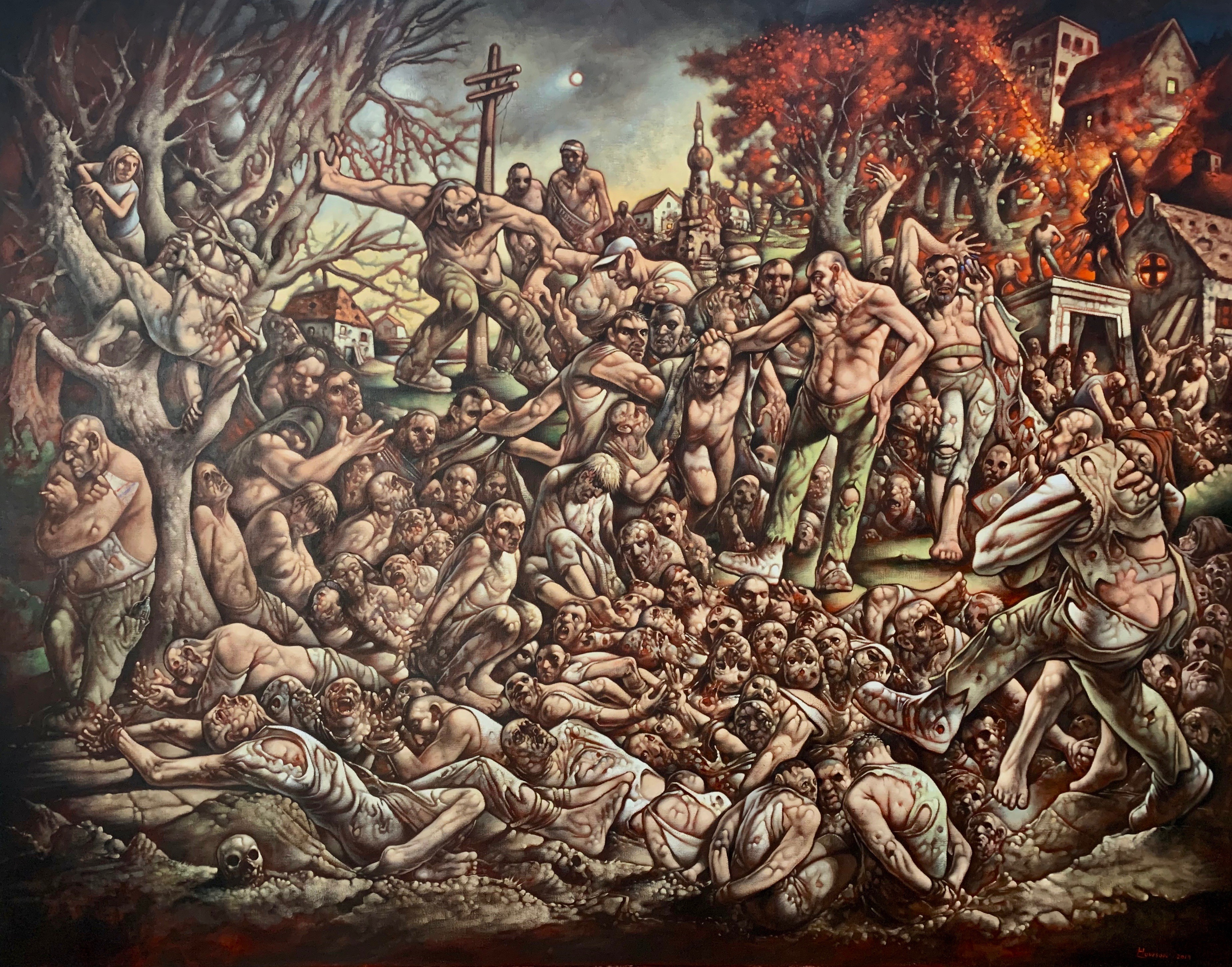

Scottish artist Peter Howson, who currently has a major retrospective in Edinburgh’s City Art Centre, complains that celebs like Depp are “taking money out of artists’ pockets”, which sounds a little bit like a disgruntled challenge to the universe. Why, Mother Earth, is he making more dosh than me? It also begs the question, how democratic is art?

As a writer, I have a certain sympathy with Howson’s pique, and have been known to silently gnash my teeth at the sight of a novel “written” by celebrities like Katie Price. I once interviewed Price, whose response to a question about her life was that she would have to consult her autobiography to “see what she had written”, at which point I was convinced that not only had she not written it, she hadn’t read it either.

Listen, I wanted to tell the book reading public, don’t waste your money on a woman who can’t make up her own story, let alone anyone else’s. But who am I to decide what is “worthy” literature?

Howson criticises Depp for exploiting his celebrity status to sell inferior artwork. “It’s just about who he is,” he argues. But at least he paints it himself. And, anyway, doesn’t Howson, known for his muscular male images, have his own unacknowledged advantage in the art world: being white and male?

Art depicts the world, and the male view of the universe has, in art, literature and everything else, been far more highly valued than the female one, or even the black male one. (And God help you, black women.)

This week, I read about a female artist whose work was found to be too big for her allotted exhibition space. Could she, maybe, just shave a bit off the bottom?

Outraged, she refused, speculating on whether a male artist would have been asked the same question. “Scuse me, Salvador, can we just chop the bottom of the canvas off your wee crucifixion sketch? Just the world bit below the cross – we’ll keep Jesus.”

Who has the right to be the arbiter of art’s ‘value’?

Howson is outraged that Depp has made £4 million from his artwork recently, selling individual prints for £4,500. “That is ridiculous for a print from someone who doesn’t have a track record of being an artist,” Howson was quoted as saying.

Well, that, my friend, is the ruthless irrationality of capitalism. Shocking, but market value. If someone is prepared to pay £4,500 for a Johnny Depp portrait instead of one by a “real” artist, who’s to say they shouldn’t?

Seeing Johnny’s art live at Castle Fine Art in S Molton St, London. #JohnnyDepp #JohnnyDeppNFT pic.twitter.com/AsQYtnnpTT

— IFOD (@ifod_net) May 23, 2023

We have had this “artistic merit” versus “popular appeal” argument before with Jack Vettriano, who claimed the issues were partly bound up in attitudes to social class.

If the person who wants Katie Price’s book doesn’t buy it, it doesn’t mean they will spend their £6.99 on Charles Dickens. Nor, if they don’t buy Johnny Depp, will they necessarily buy a Howson. They might just blow it on a trip to Barbados and have a blank wall.

In any case, who has the right to be the arbiter of art’s “value”? Value to whom?

Art that captures public imagination is important

Years ago, I interviewed Howson, a fascinating man who is autistic, and who was taxed by in-depth questions to the extent that, by the end of the interview, he needed Solpadeine and I needed to lie in a darkened room.

But what emerged in the tortuous conversation was the way art depicts the interior life of the artist. Viewing art, or reading literature, is one of the most intimate of human connections: a way of seeing inside someone else’s head; of rifling through drawers of their thought processes; of seeing the world as they see it.

“Art is a lie that makes us realise the truth,” Pablo Picasso once said. If you believe that, you can see why practitioners like Howson object to forms of artistry that have limited complexity.

“I am on the planet to do art,” he told me, emphasising that, for him, life was art and art was life. Serious stuff. Too many great artists, he said when discussing Depp last week, are ignored; too many galleries are struggling.

But isn’t that also a reason to welcome anyone who captures the public’s imagination artistically – no easy thing to do? A reason to remember the purpose of art? It may be existential, but it’s also decorative and celebratory. You hang it on your wall primarily because you like it. Or, you read it because you want to.

There’s the delight of escapism for the audience, and the joy of creation for the artist. And that includes Depp. And, yes, OK – Katie Price’s ghostwriter.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter, and Scottish Newspaper Columnist of the Year 2022

Conversation