You’re busy people, I know, so you may be forgiven if you missed the celebrations last Tuesday.

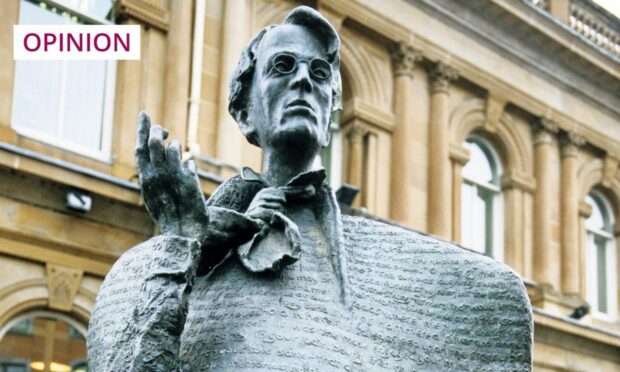

Every June 13, aficionados of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats – born on

that day in 1865 – commemorate his life and work. How exactly they do this, I’m not sure. Drink Guinness and worry, I suppose.

Anyway, if I’m honest, I only know about Yeats Day thanks to a note on Twitter from the Irish Embassy in London, which pointed out that this year marks the 100th anniversary of his receipt of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

That reminder sent me back to an English class in the mid-1980s, when we studied his poem, The Second Coming.

Perhaps the most famous of his works, it was written in the aftermath of the First World War and presents a rather grim view of the world. I loved it.

The poem is speckled with memorable lines: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”, “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned”, “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”

Even if you don’t know the poem, the chances are you’ll have heard a line or two. For the near 40 years since I first read it, I’ve carried a particular couplet with me. “The best,” wrote Yeats, “lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

In a poem filled with sometimes perplexing imagery, the clarity of these lines screams out. We recognise their truth, instantly.

Which of us hasn’t had to deal with someone so gripped by certainty – or self-belief – that they leave no room for questions? I wonder whether these lines have stayed with me because, for most of my working life, I’ve been writing about politics and its practitioners.

Of course, a necessary – if not always attractive – quality in anyone wishing to pursue and, crucially, sustain a career in politics is a degree of confidence. This, in itself, is not a problem. Confidence is a good thing and I daresay more of us should be better at it.

Rigid adherents to political ideologies won’t budge

But there comes a point where absolute, overwhelming certainty obliterates reality. We saw this happen with the rigid adherents to the ideology of Brexit who refused to entertain a scintilla of scepticism.

Those who dared suggest that departure from the European Union might have downsides were simply scaremongering. Even now, as those who warned Brexit would come at a devastating cost to the country and, in particular, its poorest inhabitants, the true-believin’ Brexiteer remains unmoved.

So convinced is he that he was right, he blames opponents to the project – powerless to affect it – rather than the project itself for its miserable consequences. The faith of the Eurosceptic fundamentalist remains unshaken.

A similar mindset may be found in the most enthusiastic supporters of Scottish independence. There is no doubt in the minds of those who participate in saltire-waving marches that Scotland is a victim of the union.

You will hear from them the claim that an independent Scotland would be richer and more successful; perhaps they’ll tell you that the only reason unionist parties wish to maintain the United Kingdom is because they are dependent on Scotland’s resources.

You may attempt to challenge these common assertions, perhaps, for example, by pointing out the existence of the Barnett formula, a mechanism that ensures public spending by the UK Government is higher, per capita, than in England. Your attempt to challenge the ideology of the nationalist will fail.

Yeats was right – be wary

And it is not only on matters constitutional that certainty drowns out scepticism. We truly are living in the era of the ideologue: a time when – during her brief, painful premiership last year – Liz Truss caused economic chaos with her belief that offsetting massive tax cuts with borrowing was in the country’s best interests; a time when, during a recent debate on the Equality Act, Aberdeen North MP Kirsty Blackman – a mother of two and former medical student – said: “I have no idea what my chromosomes are. I have an assumption that they are probably XY but I don’t know”; a time when supporters of former US president Donald Trump turned out to greet him with cheers after he left court, charged with illegally retaining top-secret documents.

Yeats’s greatest poem may be bleak, but it contains wisdom that we should continue to heed more than a century after its publication. Let’s be wary of those whose passionate intensity overflows.

Euan McColm is a regular columnist for various Scottish newspapers

Conversation