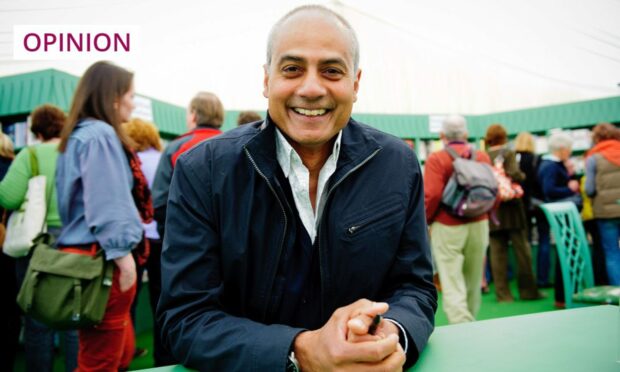

I was sorry to learn about the death of newsreader and journalist George Alagiah, two weeks ago today.

Initially diagnosed with cancer in 2014, he revealed that his condition was terminal in 2018 and died, surrounded by his family, a little over five years later. He was just 67 – taken far too soon and in unbearably sad circumstances.

But it was only when watching footage of fellow newsreader Clive Myrie announcing the death of his long-time colleague and friend live on air that I cried. Cutaways to photos of Alagiah gave Myrie a few moments to compose himself off-camera, but there was no concealing the tremble in his voice when he spoke, processing the devastating news as he delivered it.

A strange and sobering occupational inevitability of working in online or print journalism is that, some day, you could well find yourself writing the obituary of someone you once shared a desk and jokes and sandwiches and pints and leaky biros with. And, if you get an obit, you likely already know the person who’ll write yours.

It’s an intimidating task, no doubt, but an assignment many journalists see as both an honour and a duty, I think; one last act of comradeship.

When a former colleague of mine, Stephen Wilkie, sadly died (also far too soon) on Christmas Day last year, his workmates did their brother in arms proud.

So many memories, shared in his obituary and on social media, all described a (literal and metaphorical) giant of a man, dedicated to getting it right the first time at work, but also to doing right by the people around him, even while very ill. The first time I came across Stephen in the newsroom, I felt a little bit intimidated by him; the last time we spoke, he was sending me adorable photos of his new puppy.

I hope he knew how respected he was; how fond of him we all were and still are. I wish now that I’d had a chance to tell him. But I sat just a few desks away for years. There was plenty of time to tell him.

Nothing in an obit should be news to the deceased

We’re a funny bunch, humans – stubbornly terrible at talking about death in advance but then, once it comes, the floodgates open. And, when they do, it quickly becomes clear that we genuinely like and admire each other, appreciate each other’s unique traits and eccentricities, remember small but unforgettable kindnesses, always. So why don’t we say it out loud more often? Why, in some cases, do we never get around to saying it at all?

When the time comes, I hope all of us will have our favourite songs played and poems read at our funerals, and lovely, witty obits, written with care by somebody skilled. But I desperately hope that nothing lovely said at those funerals or written in those obits would be news to the deceased.

Clive Myrie’s tribute to George Alagiah is pure class.

pic.twitter.com/iFSImdzZA7— Bella Wallersteiner 🇺🇦 (@BellaWallerstei) July 24, 2023

Some people with terminal illnesses choose to have “living funerals”, where they attend their own memorial service along with their nearest and dearest before they die, hearing all the wonderful eulogies, and getting to give everyone a hug goodbye. It’s a nice idea, but not one that will be for everybody – particularly since not all of us know when the end is coming.

In another tribute that made me sob, the BBC’s Sophie Raworth revealed George Alagiah had hoped to appear live on air one last time before his death, planning to turn to the camera, as he did so many times in his career, and say a final farewell to viewers. Unfortunately, due to his rapidly declining health, it wasn’t possible. I hope, before he went, he knew how many lives he touched.

Give the compliment, say the nice thing – don’t wait until it’s too late

In Britain, we tend not to be very good at receiving compliments, often hastily shrugging them off or swatting them away like pesky insects. Perhaps that’s why we’re also not very good at giving them – we don’t want to embarrass anybody. And sometimes it can feel embarrassing to give the compliment, too: patronising, unprofessional, cringeworthy.

But then I think about the lasting power of a genuine compliment, and the glowing warmth that comes from feeling seen, understood, appreciated and loved.

If you love them, if you admire them, if they make you laugh or wow you with their intellect or do something beautifully kind, tell them

I think, as well, of all the times I’ve withheld praise and admiration for no good reason; “don’t tell him I said that, he’ll get a big head”. He won’t, of course. He’ll probably just roll his eyes and change the subject. But, maybe later – months or years later, even – he’ll think of that compliment on a difficult day and it will make things a little brighter.

It’s nice to say nice things about the people we’ve lost, and to share good memories – but we aren’t doing it for them by that point, we’re doing it for us. They’ve already gone.

Relative, friend, partner, colleague, whoever – if you love them, if you admire them, if they make you laugh or wow you with their intellect or do something beautifully kind, tell them. Tell them now, and tell them often. You won’t regret it.

Alex Watson is Head of Comment for The Press and Journal and has endless respect for talented obituary writers who do it all the time