“Most artists have an obsession that defines their work. Monet had light, Hockney has colour, I’ve got police response time.”

Of course, I was dying to see the first Banksy solo exhibition in 14 years, Cut and Run: 25 Years Card Labour, at the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) in Glasgow. Not only is Banksy the world’s most famous and celebrated graffiti artist, but he is also the most incisive and mischievous political commentator.

Straight onto the ticket website to coincide with a trip to visit my sister in Glasgow – I didn’t give her or the kids a choice.

“Another exhibition?” They asked. (We’d just returned from Dundee, where I’d booked to see Tartan at the V&A. There’s so much art to see in Scotland – festivals everywhere.) Surely that’s what holidays are for.

R announced – with an eye roll – that I had been dragging them to art galleries since they were two years old. “I’m amazed at your memory,” I responded.

In truly enigmatic Banksy style, Cut and Run had been kept a closely guarded secret right up until the day tickets went on sale. As we queued outside on a sunny and rainy Saturday in July, I observed the other eager gallerygoers. Quite the mixed demographic. Lots of groups of youngish fellas.

Bags were duly searched and then our phones were safely locked away in individual pouches. The kids were not amused. Imagine! An exhibition where you can’t take photos! Truly unusual, in this day and age, when the hordes hover en masse on tiptoes to get a blurred selfie with the Mona Lisa.

Once inside the ominous darkened corridors of GoMA, we entered another realm, lost in the force that is Banksy. A genuine activist artist: controversial, enigmatic, clever with words. In my eyes, a genius.

My sister and I, shaped very much by our working-class upbringing, would gasp at the same time. It’s emotional, she said.

The kids were enthralled, and even agreed to a polaroid photo – taken by one of the staff – in front of Banksy’s infamous tapped phone box, with the menacing spycops lurking outside. (How’s that for familial synchronicity?)

Not only do we see close up the astonishing stencils Banksy used to create some of his most famous, most powerful works, we also have examples of the larger installations. The Kissing Coppers piece has been recreated. There’s a not-a-funfair segment of Dismaland.

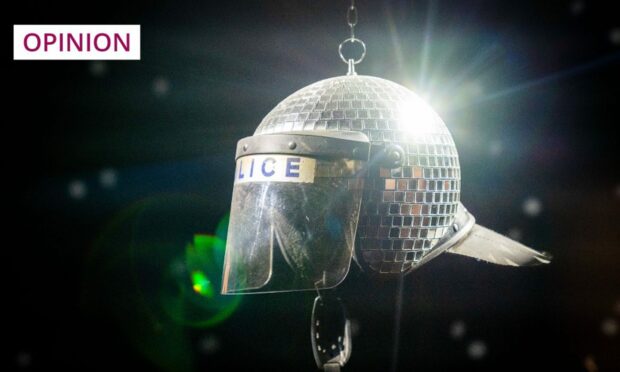

Amongst the most thought-provoking pieces for me are the ones which speak to us on police violence. The Met Ball – a shiny disco ball/police helmet. This brings back memories, and not happy ones. The life-sized police officer in riot gear, rocking back and forward on a kid’s bike, up on a pedestal. Monstrous.

The cleverest of social commentators

I’ve heard Banksy once described himself as just a “painter and decorator”. He’s the cleverest of social commentators, who leaves a memory imprint. The story behind the Union flag stab vest worn by Stormzy during his headline performance at Glastonbury in 2019 is now etched in mine. There were audible gasps from everyone who passed it.

The works from Bethlehem in the West Bank, capturing a pillow fight between an Israeli soldier and a Palestinian, prompted complete silence in my sister and me. No contemporary artist shines a light on injustice like Banksy.

As is appropriate, we (reluctantly) exited through the gift shop. Well, a Banksy kind of gift shop

I could go on and on. The thing that really got me was how personal this exhibition felt; how much of a narrative journey this artistic revolution was, and how Banksy’s visceral storytelling wove through my life. How the kids responded. How it became a shared space, and how the four of us, as a family, talked about it all day.

As is appropriate, we (reluctantly) exited through the gift shop. Well, a Banksy kind of gift shop. The kids bought Dismaland T-shirts. My sister and I chose No Borders designs (all profits going to the lifesaving Sea Watch International, whose crew rescues refugees in the Mediterranean seas).

As we left, there was a graffiti wall where the kids signed their names, and I defiantly wrote #spycops. Even the exit means something.

Donna McLean is originally from Ayrshire and is a mum of twins, writer and activist