Because I was better at writing about football than playing it, my connections with the beautiful game were always destined to be literal rather than physical.

And, whenever I did play in an 11-a-side game, it struck me very quickly that whatever minor skills I may have had were overshadowed by those of others. In addition, everyone else seemed to be bigger, faster and stronger than I – to say nothing of fitter.

I, therefore, generally stayed on the terraces, then later took my seat in the press box with the other hacks and cooed and clucked in unison with them over the groin strains and 5-3-2 formations. Not making it as a player but following Scotland to two World Cups and supporting the blue-and-white side of the Inverness triumvirate of teams back in my day instead did not diminish my love of football. Quite the reverse.

It may well be a treatise for another day but, after years of longing to be a sports reporter, I regretted the career choice the moment I became one. My eyes had been clouded by the putative glories of the personalities I had previously idolised. Once I had to deal with them professionally, I realised that few were polite, fewer still were pleasant and most weren’t all that bright.

They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes. That is very true and, yes, it’s a tale for another day.

We have seen the heartbreaking evidence of harm headers cause

Growing up an Inverness Caley fan, my theatre of dreams was not Wembley, the Camp Nou or the Maracanã. Instead, I longed for the unlikely surroundings of Telford Street Park, where the smell of the pies and the urinals at one end mingled incongruously yet intoxicatingly with the nose of the cratur being created at the Glen Albyn distillery at the other. Throw in a seagull’s cry and the roar of the crowd, and I am there today.

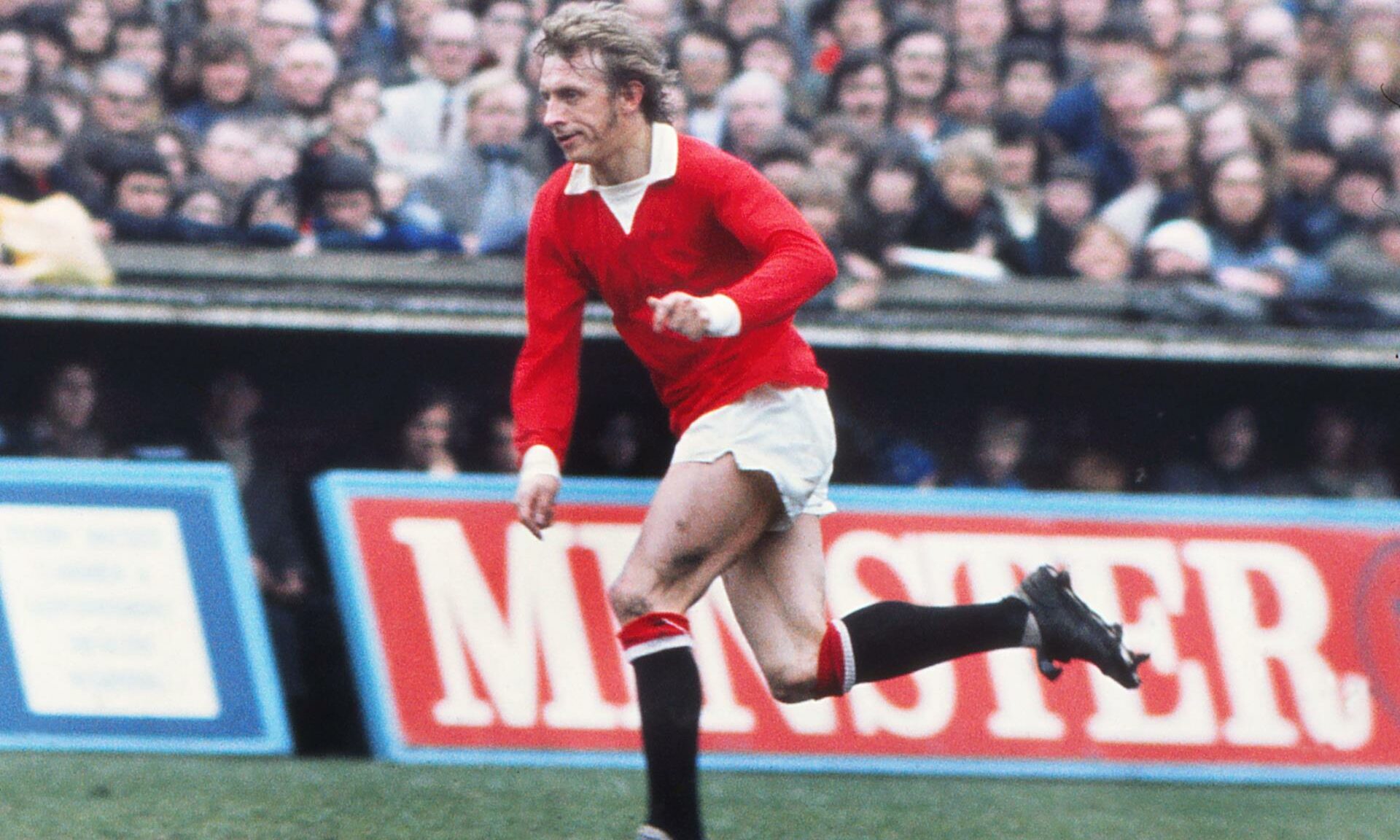

It was a hard man’s game in those Highland League days, and I mean no disrespect to women’s football. England’s Lionesses have done the sport proud in recent weeks. But in my 1970s heyday, it was all musclebound legs lathered in shiny embrocation, nylon strips you wouldn’t want to wear too close to the fire, and a ball that felt like it was made of Tungsten on wet days. And my idols blithely headed it all game long. It’s the only aspect of those halcyon days of my Caley childhood which I regret witnessing with all of my heart today.

As is so often the case, Scotland has led the way. Studies by doctors at the University of Glasgow have revealed statistics which we probably all kind of suspected but were too afraid to accept. They point to the uncomfortable truth that football is dangerous, and heading the ball can kill you.

In short, if you played professional football at the time my heroes did, you are three and a half times more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodegenerative condition like Alzheimer’s or motor neurone disease.

The staggering subset of that cohort reveals that if you played as a defender with statistically more incidence of heading the ball than anyone playing in any other position, you are five times more likely. Five times!

The statistic from the study which confirms the point without even trying is that goalkeepers, who don’t habitually head the ball, were as likely to receive such a diagnosis as someone who didn’t play football at all. It’s sobering reading, and fuels my desire to see big changes in our game.

An outright ban is the next bold step Scotland must take

The Scottish authorities have taken a bold step, and I would hope the world game follows suit. Children here may not head the ball during football training, and professionals may not head the ball in the 24 hours before and after a game.

I’d like to go further and call for a change in the rules resulting in an outright ban. If heading is not part of the game, players have no requirement to train for it – and it is during daily training sessions, with multiple blows to the head, that the danger lies.

Ask the families of late Scottish football heroes Billy McNeill, Gordon McQueen and Frank Kopel. There is no doubt in their minds that heading the ball killed their loved ones.

My childhood memories are of the boys in blue lifting trophy after trophy at Telford Street, playing fast, attacking football. But the ball was in the air as often as not.

If you take heading out of the game, you play more attractive football on the ground, like the best teams down the years have done. Children learn to play the game without handling the ball. They must learn to play the game without heading it, too.

The sport is called football not headball, and the game has a duty of care to the men and women and, in particular, the children who play it.

Mike Edwards OBE was the face of the evening news on STV for more than 25 years and is a published author, a charity trustee and a serving Army Reservist