Interviewing interviewers is a tricky business: you can’t kid a kidder, as they say.

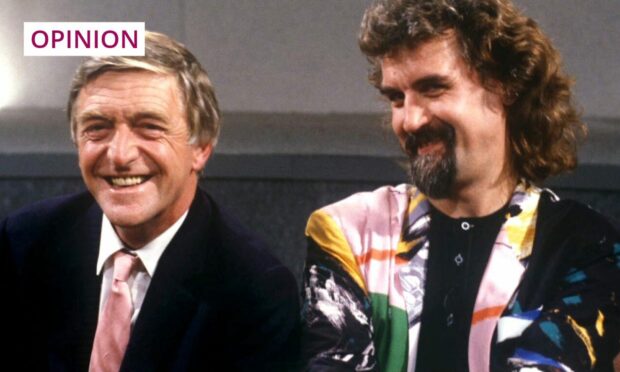

Gyles Brandreth, for example, was hilariously ebullient to the point that I wanted to say: “For heaven’s sake, stop talking, Gyles! Let me ask a question!” Michael Parkinson, on the other hand, who sadly died last week, embodied a grumpiness that could have created a whole new Yorkshire Tea advert.

Teased that he made himself sound a bit of a chancer in his autobiography, things got decidedly chilly. No, he said stiffly, he was just an unlikely fit for some of the jobs he had done, which at the time I interpreted as: “I’ll do t’jokes around here, lass. You can take me serious, like.”

He claimed flirting was an interview technique. In fact, he was doing it right now. Was he? They must do these things differently in Yorkshire.

When he pointed out he was the youngest captain in the army I said yeah, but he lied to get there, telling the army he had five O Levels when he had two. That wasn’t lying! No? That was cutting through bullshit, he insisted. What, I wanted him to tell the truth and get excluded? Was I mad? (Is that flirtation in Yorkshire, do you think?)

Well, fine, if we’re talking army captains – what do they matter? – but maybe not if he wanted to be a neurosurgeon. I’d probably prefer the qualified person to the one who gave me an unintentional lobotomy.

But, as the interview progressed, it became clear that the Yorkshire bluntness, the uncompromising accent, was merely a brittle exterior; there was a sensitivity lurking beneath that no-nonsense briskness.

‘The miner and the layabout’

He came from Cudworth, a Yorkshire mining village, and he could see from the window of his childhood home the colliery where his father Jack worked. His father’s hands were safe, comforting, but calloused from heavy physical work.

Jack wanted Michael to have soft hands, to avoid the hard labour of the pits. Journalism was the ultimate clean-hands job.

Yet, it was his mother who was “the engine” of his ambition. Highly intelligent, she had been thwarted educationally: her parents took out a loan to educate her brother only. They were still paying it back 20 years later but, in a way, his mother paid all her life, channelling her ambitions into her boy.

His parents wanted the best for Michael, lived other lives vicariously through him. His white hands and clean nails somehow captured the nature of working-class progress, yet there was guilt in there, too. “The miner and the layabout,” Parkinson told me.

Navigating guilt and grief

When his father was dying of the miner’s disease pneumoconiosis, he stayed with Michael and his wife Mary. Michael used to look at the calloused hands on the bedcover and feel guilty.

“I was ashamed of a society that convicted him, if you like, to a life down the pit,” he said, “Then there’s the guilt that I escaped and he didn’t.”

“Without the grammar school, I would have been down the pit. There was no alternative.”

Michael imagined writing an autobiography and having two hands – his and his father’s – on the cover. When he finally did come to write about his dad, his tears dripped relentlessly down onto the typewriter keys, but the result was a passage of exquisite tenderness.

He struggled with grief when his father passed, started drinking heavily and, for the first and last time in his life, went to a psychiatrist. But alcohol wasn’t his problem, just a symptom of it.

Footballer George Best once told him how, when Sir Matt Busby carpeted him, he counted birds on the wallpaper over Busby’s shoulder. Parkinson tried the same tactic with the psychiatrist. “I stared over his left shoulder, counted patterns on the wallpaper, and nodded.”

Two years after his father’s death, he found a photograph of his dad and cried for an hour. And that, in his Yorkshire way, was that.

Fathers and sons, their hands linking the generations

All through the interview, his “minder” had stood brooding, then rudely tried to terminate the conversation early. Parky saw my hackles rising and smoothed things over beautifully, giving me his number in case I needed to check anything.

“Who on earth was that?” I asked someone afterwards. “His son.”

He had three sons – would have loved a daughter – and they all lived within three miles of him. His son put my back up that day, but I empathised with him when I heard news of Parky’s death; with the trauma of losing a father, as Parkinson himself had so vividly described.

My interview with Michael Parkinson taught me how important it is not to judge immediately on the basis of hard exterior, but to dig deeper

Fathers and sons, their hands linking the generations. Calloused skin turning soft and milky white. A sign of progress, of different kinds of exploration.

And, just as those mining hands dug deep to find the jewels of coal in the mines, my interview with Michael Parkinson taught me how important it is not to judge immediately on the basis of hard exterior, but to dig deeper to the hidden seam of humanity inside which delivers so much more of value.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter