I was on a train to Edinburgh at the weekend when I noticed a group of young boys aged about 17 or 18, slumped across some nearby seats.

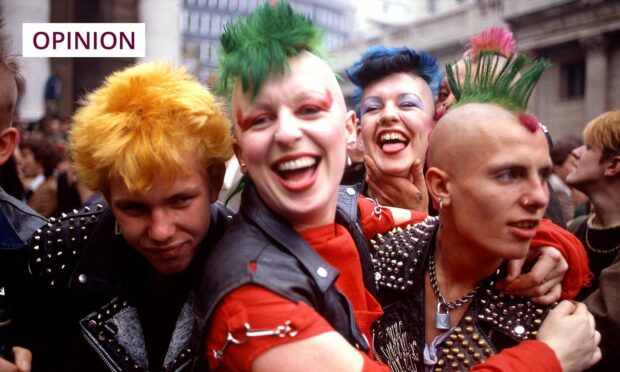

They were punks, not in the modern, “deadbeat” sense of the word, but in the classic 1970s way: hair gelled into long spikes, chains hanging from torn jeans, Docs on their feet, and denim and leather jackets with the names of bands such as The Clash, The Damned and Buzzcocks scrawled across them.

They were perfectly decent and harmless kids, as indeed most punks were back in the day, and perhaps they were only on their way to a fancy dress party. But the whole thing appeared more authentic than that, like they were searching for a non-mainstream identity and had settled, for however long, on this one.

The sight of them cheered me greatly. You could argue it was all a bit pastiche, that kids should be finding original ways to express their teen rebellion, but people were staring at them. They looked transgressive. They looked awful. It was glorious.

This visual statement, whatever was meant by it, spoke to something that has been bothering me for a while. So has an interview given by the great Ken Bruce, in which he reveals that one of the reasons he quit Radio 2 after 31 years was that he was sick of playing newly released music that didn’t appeal to him.

“There was a point of saying that I can’t enthuse over all the new music I’m having to play as much as I could over the old music,” he told a podcast. “And I didn’t want to get to the stage where I was badmouthing some of the music [or] pretending to like it.”

I’ve no idea what Bruce’s musical tastes are – though I note that the first two songs he played on Greatest Hits Radio, freed from the strictures of the dreaded BBC playlist, were The Beatles’ Come Together and Manic Monday by The Bangles, bangers both. I can only imagine the contentment that comes from being able to ignore entirely the latest soporific ballad from Ed Sheeran, or the new Tony Hadley single, which, dismal though it is, was recently on heavy rotation as Radio 2’s single of the week.

Bruce is a musician himself, and plays drums in a cover band with the excellent name of No Direction, so his connection to the idea of the song will be real and deeply felt. And I believe that the malaise he hints at is a genuine problem in the modern industry.

Modern music is lacking in rebellion

I’m not saying that the charts and the radio haven’t always been dominated by bland, uninspired dreck. Nor am I making the case that the music I like is objectively better than the music anyone else likes. It’s a subjective thing for us all, formed by instinct and chemistry, timing and age.

And it’s not as if the mainstream doesn’t produce great records – the last Harry Styles album was brilliant, and he’s a superb pop star. I tap my foot to tunes by Ariana Grande and Dua Lipa. If every new song challenged the consensus, there would be no consensus, or anything to rebel against.

But I do wonder where the rebellion even is. Where is the music that changes the way you think about the world, that deliciously confuses your ears, that changes forever the way you listen? Where are the lyrics that make your hair stand on end, the subversive bands that unignorably snarl and bite their way to fame and ignominy?

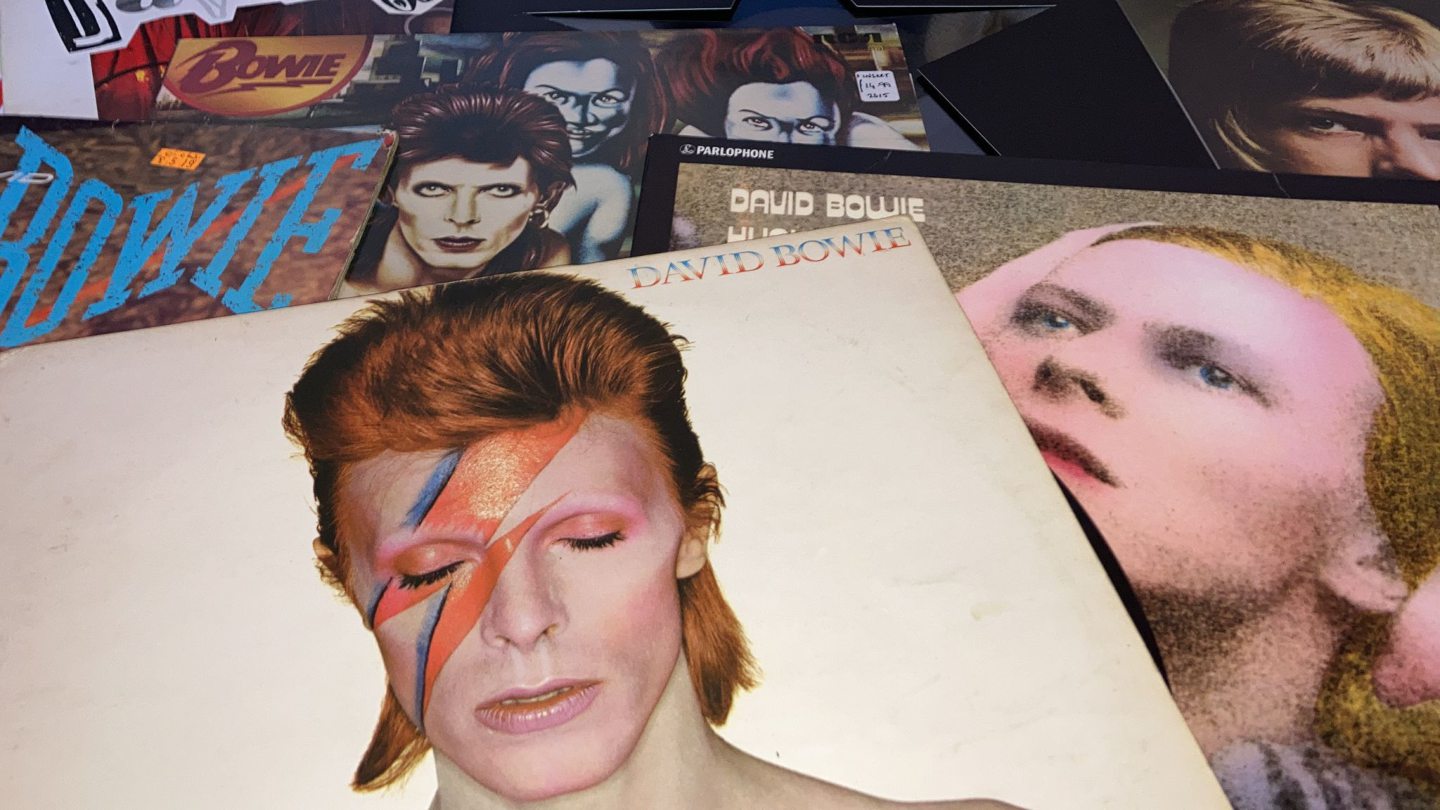

Where is the restless, bad-tempered innovation that at first frightens, then changes the mainstream, as The Velvet Underground and David Bowie did, as the spitting punks did, as those swaggering Manc nihilists The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays did? The electronic music scene birthed large-scale raves that forced a petrified Tory government to change the law. At its outset, grunge was a roar of raw pain and frustration. Even Britpop, a much tamer affair, had its moments.

Where is the music that will make me feel like an old fart?

There is much to admire in today’s alternative scene. Young women such as Mitski and Self Esteem’s Rebecca Lucy Taylor have found a voice and a form of expression that rails against misogyny, the male gaze, and the silos into which society expects them to fit. Grime is only the latest expression of young black identity. But, still, it feels as if there’s something missing – a spirited fury against the age that can unify a youth movement in its moment.

I expected to reach middle age grumbling, as previous generations have, that new music is too crazy and tuneless and unlistenable for me

Perhaps the relative unimportance of the music charts or the lack of a coherent music press makes it all harder. We had Melody Maker and NME and a fanzine culture that focused attention on and supported burgeoning new scenes. Equally, though, access to apps such as GarageBand make it easier than ever for young people to make their own music, and social media enables them to share it freely and widely.

I expected to reach middle age grumbling, as previous generations have, that new music is too crazy and tuneless and unlistenable for me. Actually, it’s not crazy and tuneless and unlistenable enough.

Given all that kids have to put up with these days, from economic decline to climate change to Brexit to a freakishly unstable jobs market, where is the sneering, contemptuous artistic revolution? Where, in other words, is the music that will make me feel like an old fart?

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland