In the town where I grew up, there was an old cinema. For the 18 years I lived there, it sat boarded-up, empty and silent, slap bang in the centre of the high street.

Even as it decayed, it was an impressive sight – a tall, grand, castle-like building, with turrets. The iteration I saw nearly every day as a child had been converted in 1937; the original building (dating back to 1886) was even more striking.

Like lots of formerly popular picture houses, it stopped showing films and became a bingo hall in the 1970s then, later, an amusement arcade. So, really, it wasn’t much of an old cinema at all by the time I knew it. Yet, I felt its absence.

I never saw the inside, but I regularly imagined what it might have looked like in its busy, glamorous heyday, as well as what a modern refurb could turn it into. I imagined a reality where my friends and I could go to the movies without first taking a bus or train or negotiating a lift from a parent – simultaneously freeing and safe.

I moved away for university, finding myself a 10-minute walk from the Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA) centre. I never got over the novelty of living closer to a world-class cinema than I did to a McDonald’s.

Every time I visited home, the old cinema was still there, rotting but reliable. Then, one day, it was gone. Vanished. A building that had been part of the town’s landscape for more than 130 years, completely demolished, leaving a huge hole in the high street. I felt sick when I saw it.

Saving, repairing and reopening that old cinema wouldn’t just have been an exercise in preserving the past – it would have been an incredible, important investment for the future. Seeing the success of the likes of The Montrose Playhouse and Arc Cinema in Peterhead makes me desperately wish I had done more to fight that demolition.

Screen Machine provides a vital cultural link for so many communities

Now, another cinema I feel an affinity with is in danger of disappearing. This one isn’t made of bricks and mortar, but it will be sorely missed by far more than just one local community if it’s forced to close its doors permanently.

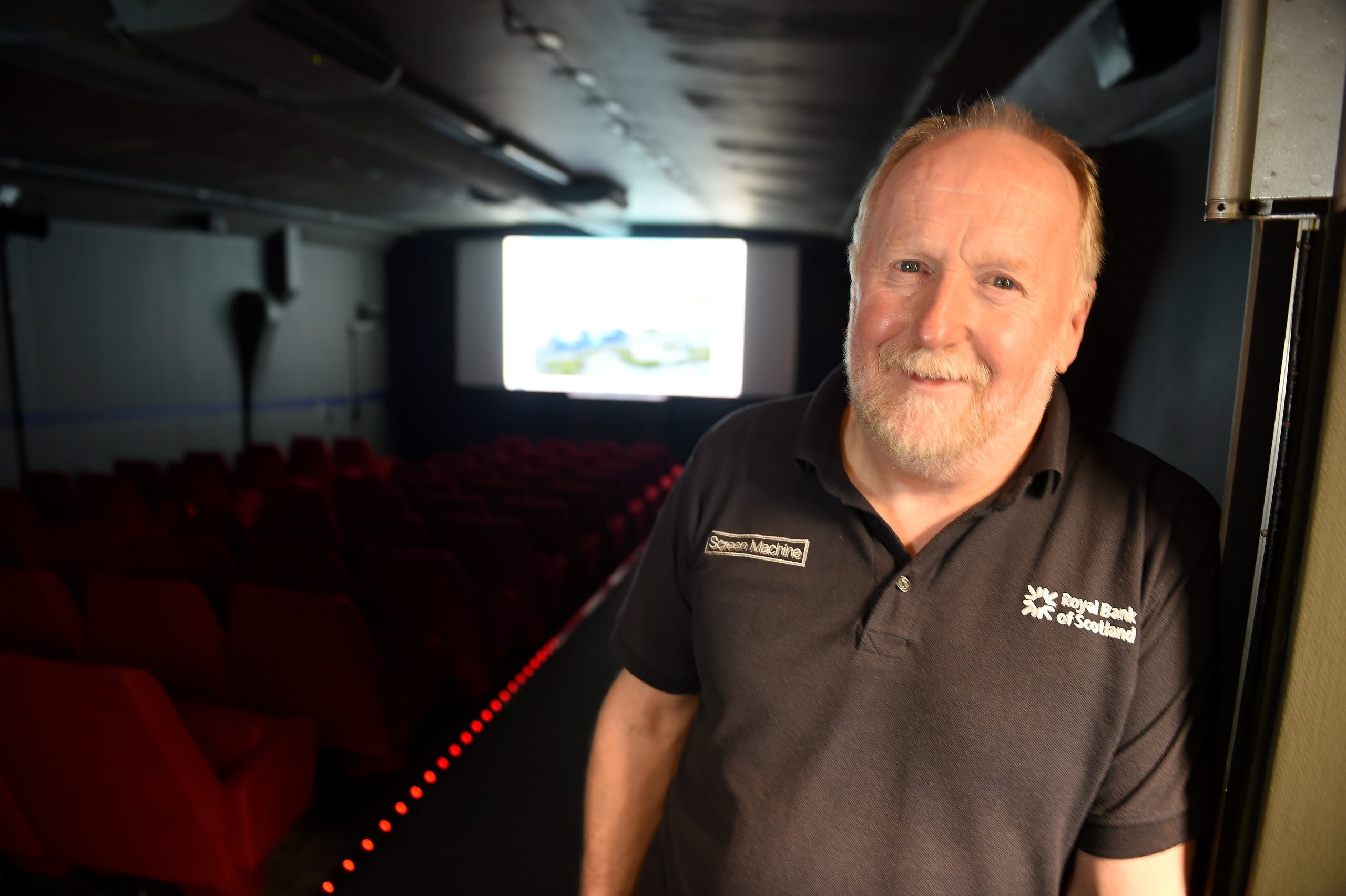

I’m talking, of course, about the Screen Machine – the travelling cinema loaded onto the back of a lorry that regularly visits towns and villages across the Highlands and islands, bringing the people who live there the latest movie releases.

When I first heard about the Screen Machine, I thought it sounded too whimsical and wonderful to be real. The service, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this month, is whimsical and wonderful, but it also provides an absolutely vital cultural link for people living in the north of Scotland.

After retiring the long-serving Screen Machine most visitors know, its operators need to raise £1.4 million to buy a new one. They’re asking the Scottish Government to provide 50% of the overall cost so they can put down a deposit and get the building of the new cinema underway – production is expected to take between a year and 18 months.

Once government investment is guaranteed, fundraising for the full balance will start in earnest. But, without Scottish Government backing, that moment may never arrive.

We have to act now

As soon as you’re inside the Screen Machine, you forget it’s not a permanent structure. Its clever design means that, when stationary, the lorry’s trailer extends until it’s as wide and long as a medium-sized multiplex screen. The projector and sound system are top of the range and, staggered to avoid any neck-craning, the seats are bright red, plush and comfortable.

Community cinemas are fantastic, but sitting on folding village-hall chairs or church pews to watch a film isn’t always an ideal experience. The Screen Machine is the best of both worlds, providing a sense of occasion and a little bit of luxury when it pulls into town.

Cosy and warm while wind and rain battered Mull just outside, I thought about the other people through the years and all over the north who had their own preferred Screen Machine seat, and sank into it habitually. I wondered, had that old cinema in my hometown been open as I grew up, if I would have had a “usual” seat there, and what I might have learned about the world and about myself while occupying it.

I don’t want the Screen Machine to be a relic of the past for young people in the Highlands and islands, and I bet you don’t either. The cinema needs our help to survive, and the best way to give it is to write to the Scottish Government – to the first minister, your MSP, MP or councillor – and ask them to make this funding an urgent priority.

There’s still hope, but cinemas aren’t saved by accident – we have to act before all that’s left is a huge, gaping hole where heritage, knowledge, inspiration and joy should be

In Dundee, my beloved DCA is also under threat of closure. But, in Aberdeen, the Belmont Cinema is to be reopened by passionate community campaigners who love film and their city. Things are looking up for the Filmhouse in Edinburgh, too.

There’s still hope, but cinemas aren’t saved by accident – we have to act before all that’s left is a huge, gaping hole where heritage, knowledge, inspiration and joy should be. To me, cinemas are magical places, and the travelling, shapeshifting Screen Machine might be the most magical of all.

Alex Watson is Head of Comment for The Press and Journal, and her favourite film is Ghostbusters