If you open a can of Scotch broth, you don’t expect chicken soup to slide glutinously into the pan. It is what is says on the tin.

Unsurprising, then, that Russell Brand – who has made a living out of turning his “sex addiction” and “depravity” into unappetising comedy routines about sexual aggression, forced oral sex, and manipulative promiscuity – should find himself embroiled in a sex scandal. The clue was always in the self-applied label.

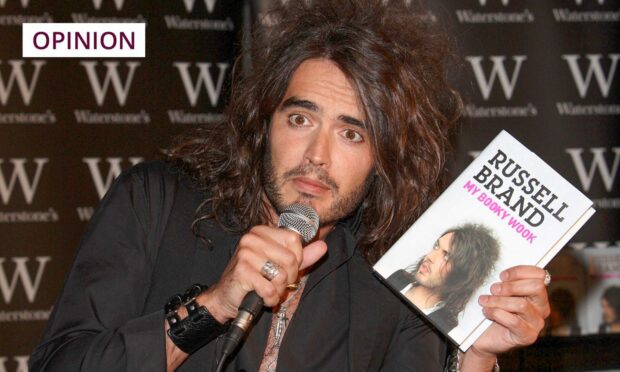

For legal reasons, let’s leave aside current accusations and I’ll tell you, instead, about meeting Brand around 2008, when his autobiography, My Booky Wook was published. In he swept – 15 minutes late – a satanic figure in black with a carefully constructed, “careless”, black beehive, from which bats might fly, and an entourage who appeared to adore him almost as much as he adored himself.

He took one look at my black velvet coat, declared he was being interviewed by a “gothic duchess”, and smiled charmingly: a safe and often successful approach for him. Sadly, I had read My Booky Wook and was fully aware that this golden start was a false dawn. The least you can do for a person so intent on charming you is make an effort to be charmed, but it wasn’t going to last. That much I knew.

Mainly because My Booky Wook was, at best, a sad affair, revealing a badly damaged man who wanted to suppress his addictions and emotional wounds by presenting them as comedy. It was confusing, like a cheap tin of baked beans masquerading as haricot vert. His sometimes tragic life was presented as a piece of performance art. Dark and disturbing things were simply “material”, obliterating any normal emotional responses of pain, anger, resentment or hurt. Only laughter was left.

An unhappy, disturbed boy who grew into a dysfunctional adult

Take, for example, his relationship with his father. Brand’s parents split when he was a baby and he had limited contact with his dad, but enough to recount watching his father’s pornography, aged four. Even that failed to register with him as a developmental red flag. Well, he maybe wouldn’t let his own children do it, he admitted, but, “I never feel, ‘Oh my God, and then I watched pornography.’ I thought it was good.”

His father influenced him psychologically, particularly his attitude to women. Paternal approval only came, he acknowledged, when he demonstrated his ability to exert power over women. At 16, he had sex with a Thai prostitute while his father entertained two others in the same room. He had little comprehension of how bizarre that was. Nor how unfunny his “amusing” story was about a row with a woman he bedded who complained when he climaxed and she didn’t. He spat in her face.

“I was like, ‘oh my god, he raped me’”

A woman shares her story about her experiences with Russell Brand with @C4Dispatches in a joint investigation with @thetimes.

Brand denies all accusations including rape, sexual assault and controlling and emotionally abusive behaviour. pic.twitter.com/XtNV5s91gk

— Channel 4 Dispatches (@C4Dispatches) September 16, 2023

That isn’t funny, I said. Well, it was funny the way he wrote it, he protested, reading verbatim from his book and laughing at his own prose. Still not funny. Brand retreated into quietness, almost surliness, but using humour inappropriately made him appear devoid of appropriate reactions or empathy.

A neighbour sexually assaulting him as a child was dismissed in a few lines of “comedy”. His description of befriending an old man and then deliberately destroying his beloved flower bed was told like a joke. None of this had the effect he was aiming for. He didn’t sound like naughty little Russell, the mischievous apple scrumper. He sounded like an unhappy, disturbed boy who grew into a dysfunctional adult.

Pointing out he wasn’t funny left him feeling out of control

This was not a version of his story Russell liked. Yet, he admitted constantly trying to fill a void in himself and discussed his lack of sexual control quite openly that day. “Preceding it, all that matters is orgasm,” he admitted. “I need it. I must have it. After orgasm, it’s, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?'”

It seemed that only when his audience laughed at this void did he feel in control of his own darkness. Pointing out that using and abusing was not funny left him feeling out of control. “You’re not happy with this interview, are you?” I said. “No, not really,” he replied. He wanted to extend it to make it “end well”.

Those questions, he said, pointing at my notes… Could he read them? No. But I’m making him out to be a nutter, he protested. No, I am discussing what he wrote.

He loved his mother because she ‘adored’ him unconditionally and laughed at him no matter what he did, just as his audiences have done for decades

The trouble with people who want you to think they are colourful and zany and different from everyone else is that, when you question their abnormality, they suddenly want to be John Smith next door. Strange? Me?

I felt sorry for Brand and his empty chaos and his buried pain that day. Sorry, but unnerved. As long as there was laughter, he was king and he was happy. He loved his mother because she “adored” him unconditionally and laughed at him no matter what he did, just as his audiences have done for decades. But it was always pretty obvious with Russell Brand that, one day, the laughter was going to stop.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter