In 2015, Bill Gates told a conference that if anything was likely to kill over 10 million people in the next two decades, it would probably be “not missiles but microbes”.

In other words, not a war but an infectious virus, like the 1918 Spanish flu. Yet, global investment had been in nuclear deterrents rather than virus prevention. Two years later, in spring 2017, Time magazine’s cover read: “Warning: the world is not ready for another pandemic”.

Bill Gates and Time journalists were not prophets. Scientists had been warning governments to prepare for a major pandemic for years before Covid struck. Predictably, politicians stuck their fingers in their ears. Selective deafness is one political speciality. Here’s another: the public inquiry.

Inquiries often feel like the societal equivalent of the sitcom policeman; the daft plod who strides up to a corpse and says: “‘Ello, ‘ello, ‘ello. What’s ‘appened ‘ere then?” Well, I think someone may have died, officer.

True, inquiries are sometimes necessary. They raise public awareness, reveal hidden truths, and give voice to victims. But there must be a better, less cumbersome, way.

When it comes to Covid, does anyone doubt what happened? Inquiry headlines so far: Matt Hancock is “desperately sorry”. Thoughts, anyone? Johnson behaved like a clown, Cummings like a foul-mouthed bully, and the Tory government in general was corrupt, chaotic and misogynistic. Which bit is a surprise?

Who benefits, other than lawyers and PR firms?

The cost of exploring Covid questions that have already been publicly dissected hit the £85 million mark before the inquiry even began. Half a million has gone on PR consultants alone, and taxpayers face an estimated final bill of around £200 million. Who benefits, other than lawyers and public relations firms?

Take the Department of Health and Social Care, which oversaw the return of potentially infected Covid patients from hospitals to care homes. It has hired legal firm Pinsent Masons, on a £2.2 million contract, to defend the indefensible, while the Cabinet Office has hired the same firm for £7 million.

So, essentially, the public are hiring lawyers to ask politicians the right questions, while simultaneously paying others to ensure they avoid answering them. Brilliant, isn’t it? Yes, Minister it is. Sir Humphrey would be terribly proud.

Then there is the cost of inquiry figureheads. The chair of the inquiry into child sexual abuse, for example, Alexis Jay, received £185,000 (plus £35,000 in accommodation costs) per annum for eight years. Compare her payment of around £1.5 million to compensation payments to victims.

Inquiry reports in 2026 – after next general election

All of it feels like expensive displacement activity to convince the public that accountability exists. The Covid inquiry wants to know about “resilience and preparedness”. We weren’t and still aren’t. “UK decision making and political governance?” Eh… Boris Johnson.

“Impact of the pandemic on healthcare?” Catastrophic. “Vaccines?” The rich countries stole from the poor countries, with pharmaceutical companies the overall winners. Again.

Mock pandemic exercises were carried out long before Covid, but 2017 recommendations have still not been implemented

Worse, the inquiry reports in 2026, after the next general election. Those most responsible will be buried in that great political graveyard in the sky. The plan appears to be to publish answers when we have forgotten the questions, and when there’s nobody left to blame.

Or when we are too ill and distracted with the next pandemic to care. Ay, there’s the rub. According to the government, the main purpose of inquiries is “to prevent recurrence”. Estimates suggest it would cost $5 per person to prevent pandemics. The cost of actually dealing with one has been $1 trillion. It would take 500 years for prevention to cost what cure has.

Mock pandemic exercises were carried out long before Covid, but 2017 recommendations have still not been implemented. Why spend millions on more recommendations when we ignored the first lot?

Short memories and shallow pockets

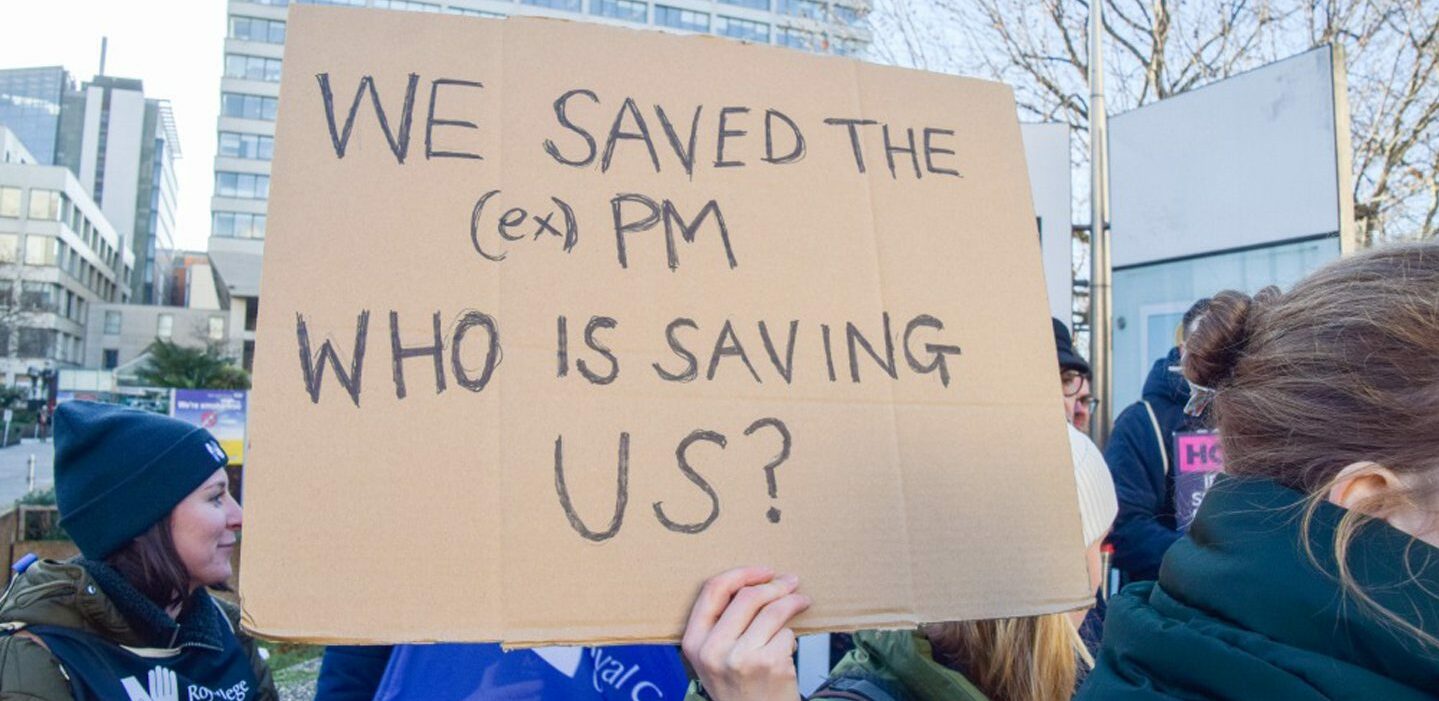

Outside the inquiry room, Covid injustice continues. Apparently, we cannot afford to pay health staff sufficiently, or support them in times of sickness. Those suffering from long Covid – an under-reported condition Boris Johnson dismissed as “bollocks” – are now being sacked.

We can pay lawyers and PR firms to perform cartwheels in an entertaining but grotesquely expensive circus, but when it comes to those who actually dealt with the pandemic – and will deal with the next – we have short memories and shallow pockets.

We are not ignorant of pandemic risks. Nor, say environmental experts, are we helpless. The next pandemic is likely to be linked to animals, and also to the way humans interact with the environment. Preventative measures include reappraising our relationships with animals, reforming farming methods, controlling greenhouse emissions, restoring ecology, tightening lab controls and improving disease surveillance.

So, do we really need to spend millions to hear the Department of Health attempting to justify dodgy PPE contracts to Michelle Mone? Or Boris Johnson vaporising like Banquo’s ghost to scream that he never went to ANY PARTY, he only ate a sausage roll?

Why “investigate” a past that we all understand because we lived through it? Those millions could be better used to ensure a future.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter

Conversation