When it comes to scams, there are those who make it an art form, prompting a soupçon of grudging admiration thrown into the hotpot of your angry outrage. How do they dream these schemes up?

But, however apparently sophisticated, the best are essentially simple. My latest favourite involves the taxpayer paying astronomical sums – compulsorily – to fund a wealthy family and their many historic buildings. Said family live tax free, but decide in difficult economic times to set up a scheme in which those who pay for their house are charged £100 to enter it and glimpse a limited number of the rooms they fund.

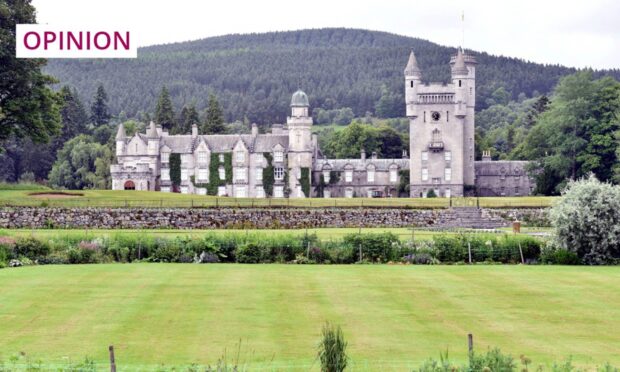

A brilliant addition is that if they want a cucumber sandwich and a wee scone thrown in, that’s another £50, ta very much. Welcome to Balmoral and the tax haven House of Windsor.

The accounting firm BDO, which compiles an analysis called “Fraud Track”, reported that fraud cases last year rose by 18% to a three-year high, with high value cases increasing by 60%. That made 2023 the second worst for fraud in the last 20 years, with the report warning that AI-generated scams were an increasing threat.

Abba-type avatars of King Charles and Queen Camilla are all the proposed Balmoral tours lack. They are due to end on August 4, because that’s when the royals’ annual holiday is scheduled and, obviously, you wouldn’t want the inconvenience of your landlords being shepherded into your spare rooms when you are actually à la maison.

One rule for King, one rule for commoner

The interesting thing is that the public largely associate scams with desperate, inept grubbiness. Who hasn’t had a variation of the email from Nigeria claiming, in less than perfect English, that your best friend has been robbed at knifepoint, while back home their cancer-stricken son or daughter needs emergency private medical care, and would you care to temporarily donate a substantial sum which will, of course, be paid back to you in brighter times? We recognise this for what it is, yet there are certain organisations and institutions that we consider so trustworthy, we don’t see through their manipulations.

Scams take advantage of people’s weakness or naivety. The Balmoral plan not only involves the highest entry fee of any royal residence, it is exploitative and disproportionate to what is on offer. Low earners contribute taxes but are unlikely to afford a visit.

In any case, if I buy something in a corner shop and, on leaving, the shopkeeper wants me to pay again because I have only paid for the goods, and taking them out, dearie, is extra, am I going to curtsey and say: “Yes, of course, Sir”? Or will I see the demand as an outrageous, blatant attempt to fleece me of more cash? One rule for King, of course, and one for commoner.

Scams depend on misplaced levels of trust

And when the chiefs of a trusted institution, like the Post Office, declare in a courtroom that I am guilty of fraud when they know I am not, who is going to believe me? Will people believe that the once respected Post Office is lying through its teeth in a self-protective, institutional scam – or will they believe that I am a lowlife thief? Even most in-the-know politicians turn the other way, because to do otherwise is difficult and will involve destabilising public trust.

Or, when an instrument of government, like the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), prosecutes thousands of carers, as has been recently reported, do we immediately assume that, since it’s the DWP, it must be acting ethically and it’s a fair cop, guv?

It is interesting that the most draconian attitudes by government departments are reserved for ordinary, struggling people

Carers are entitled to earn a set wage in addition to carer’s allowance. If they go one pound over, they encounter a “cliff edge” penalty, meaning they lose the entire benefit instead of the excess. This makes them liable for huge payments if the debt amasses over time. The DWP has IT systems capable of ensuring carers are informed if they exceed the limit – but they largely aren’t until substantial debts are owed.

A 2019 investigation by MPs concluded that most of the irregularities were genuine errors and should be waived. The DWP disagreed. Given the amount carers save the NHS and social services, it is interesting that the most draconian attitudes by government departments are reserved for ordinary, struggling people and not tax-avoiding, multi-million pound companies.

The National Audit Office even discovered one carer on benefits who was asked to pay off a £20,000 “debt” over 34 years. “It’s the DWP who are the criminals,” one victim was reported as saying.

Scams, manipulations and social injustices depend on misplaced levels of trust. On believing in things that should be examined more closely. Why do we suspend disbelief when encountering society’s biggest players? We assume that royalty, big business institutions and government departments behave, unlike scammers, with the highest levels of decency. We really shouldn’t.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter

Conversation