If you switched Line Of Duty off after the weak opening episodes then catch up urgently. Series six is a return to form.

Not only are the plot twists and cliffhangers compulsive pulp fiction, but a new seriousness is emerging. Writer Jed Mercurio, famed for his storytelling, has something big to say.

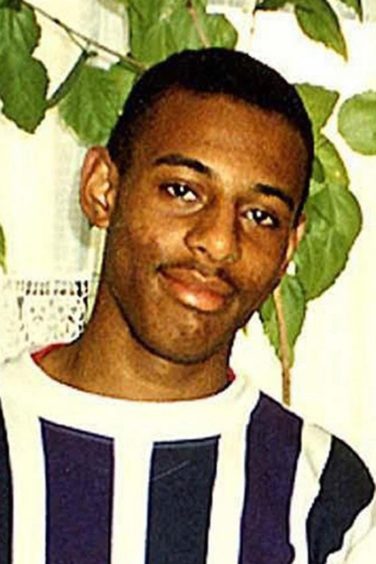

Introduced to the drama last Sunday was a character called Lawrence Christopher, a fictional murder victim of a racist attack. The name is a composite of two real cases – Stephen Lawrence and Christopher Alder.

Stephen Lawrence was killed by a gang of five white thugs for kicks, on April 22 1993. The subsequent police inquiry was inept. Christopher Alder died of a head injury in a police cell in 1998. Both victims were black.

Mercurio draws comparisons with no delicacy. The huge TV audience are left in no doubt the story line is inspired by real life. That it remains potent, and visceral, exactly 28 years after the awful crime is testament to how Stephen Lawrence’s death speaks to the heart of our society.

This week a court in America convicted Derek Chauvin, a policeman, of murder for using excessive force when arresting George Floyd There’s a sense that the verdict is a turning point in addressing white cop terror towards black citizens, that America no longer tolerates carte blanche racism.

President Biden applauded the verdict, saying it was “a giant step forward in the March towards justice in America”.

It is worth a whoop of joy, given the previous immunity of cops in the American court system, but it is an outlier. We wish it to be a landmark. It might just be a scratch.

The equivalent moment happened in the UK in 1999. Sir William Macpherson was asked to inquire into the police handling of the Lawrence case. As the Guardian’s obituary of Macpherson, who died in February of this year, notes:

“The Lawrence family had to be convinced by Straw (Jack Straw, Home Secretary) that a white, retired judge who lived in a Scottish castle was the right man for the task.”

Sir William was an example of a once common Scottish type, the rigorous, independent thinker. A credit to his family, clan and country.

His report of 1999, based on a thorough examination of the evidence, concluded the Metropolitan police had failed to deliver justice because of “professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership”.

He recommended changes to the double jeopardy law, which led to the conviction, eight years later, of two of the racist criminals who had killed Stephen Lawrence.

Landmark judgement but what changed?

Perhaps more importantly, by coining the term “institutional racism” he legitimised a debate about how the establishment treats Black and Asian people.

At the time it felt like a landmark. Cops were being called out as racists. Their racism was drawn from a culture of white supremacy in British society. The liberal myth of equality was a front behind which brutal prejudice thrived.

This seemed revelatory at the time. Someone had finally admitted the obvious. Surely change must come?

That is not what happened. In fact, the Lawrence case and the Macpherson inquiry aired issues about racism which the British public found debatable.

I’m not saying the Lawrence case and Brexit are directly connected, nor that Brexiteers are racist. Only that the trend of social change went in unpredictable ways

The UK became ever more mixed in terms of race and religion; the public ever more tolerant of sexual variation. But the following decades were characterised by the emergence of white nationalism.

The single biggest political event to follow was Brexit, an idea which in 1999 was for fringe fanatics only. I’m not saying the Lawrence case and Brexit are directly connected, nor that Brexiteers are racist. Only that the trend of social change went in unpredictable ways.

This is evident in the USA. Chauvin is convicted in April. A triumph for liberals. In January a mob attacked congress, driven on by a popular president who openly name checked white nationalists.

The stuttering way society evolves may explain why the Lawrence case is still so vivid. A student was kicked to death in daylight while waiting for a bus in London. It was obvious who had done it. The police messed up the investigation because of a loyalty to the white community.

Inquiries began, and stopped. Court cases failed for lack of evidence. The men responsible brazened it out, winning admirers in the process. An inquiry exposed institutional racism, suggesting things might change.

But April 22 is Stephen Lawrence Day. A moment to remember the unlucky man who happened to catch the eye of five white boys raised to become racists.

If the Lawrence family thought we’d all learned the lesson and moved on, they wouldn’t have designated a day of remembrance.

Popular culture wouldn’t still refer to the case if the issues had been resolved.

Line of Duty’s team are dedicated to searching out bent coppers. In truth, it’s a drama based on a bent society – where leadership still fails and prejudice is embedded in institutions.

The story moves on. Some things change, some stay the same. But it’s not until American police stop terrorising black citizens or British society becomes properly equitable that the drama ends.

And there’s no telling if that’s any closer.