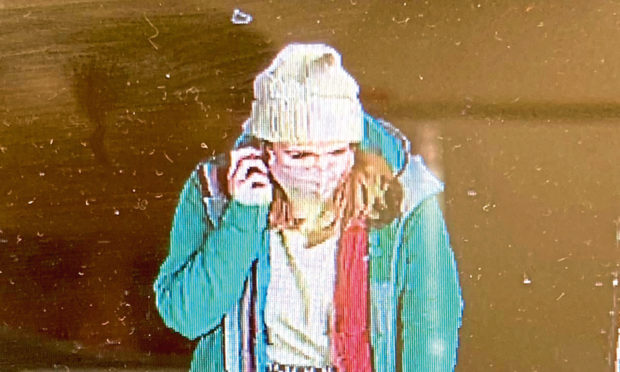

In the final CCTV pictures of Sarah Everard, it is the insignificant detail that seems so peculiarly poignant now – the trainers and white beanie hat suggesting relaxed ease in the face of unknown and imminent danger; the face mask protecting her from entirely the wrong threat.

Then there’s the slim fingers curled round her phone, and the youthful stride that, shortly after those images were captured, was halted completely. And in the midst of the anger and sadness those images spark in all of us is a sense of bewilderment at the ruthless pendulum swinging between life and death. Alive. Not.

For so many reasons, Sarah Everard has unleashed a wave of female anger that is gradually gathering momentum. She seems so young and vibrantly alive in those pictures, not vulnerable. Yet, that walk home was to be her final one. A man decided.

But there is more than that, more than this individual, gut-wrenching example of how much less free women are than men to walk alone at 9.30 in the evening.

This is about systemic problems. Cressida Dick may head the Metropolitan Police but the male machine beneath her rolls on regardless. Figureheads are useless to the rest of us. Well done, Cressida, but how did you help Sarah?

Compare the shocking scenes of male officers violently restraining peaceful female protesters at the vigil for Sarah, with scenes from Scotland when Rangers fans gathered recently outside Ibrox to celebrate winning the league.

Both events broke Covid rules but were handled completely differently. And what sprang to my mind after viewing both was the recollection of writing a story years ago about female prisons, and being told by men in the system – governors and wardens alike – that non-compliant women were treated far more harshly by the justice system than non-compliant men.

So in Scotland we had – mainly male – policemen taking a hands-off approach as the – mainly male – fans danced around a stadium before plundering their way through George Square, causing thousands of pounds worth of damage.

Some of them were men who would struggle to shed a tear if their granny died, but bawl like infants if their team gets promoted or relegated. And before anyone writes to tell me how sexist that is, and women are involved in football too – yeah, but not many, and not in power structures.

Female football commentators are derided and men get to make (and break) the rules. Like foolish, foolish, Rangers manager Steven Gerrard, who labelled the Ibrox scenes “inevitable”. Inevitable?

Our society seems to assume that men are too powerful to be contained, and women too obedient not to be controlled.

People can’t go to weddings or funerals. They can’t visit their elderly parents in care homes, or their loved ones in hospitals. What’s inevitable about visiting Ibrox? In fact, why is football even a business exemption during Covid – except that it is run mainly by, and for, men?

Our society seems to assume that men are too powerful to be contained, and women too obedient not to be controlled. Men gather unchallenged, while women are left sprawling on the ground, with policemen restraining their arms behind their backs. How dare women defy authority!

More from our columnists

-

Rt Rev Anne Dyer: High time misogyny made a hate crime

-

Chris Deerin: Women captive to sins of men until male toxicity deadly pandemic vaccine found

The recent female outpourings are about Sarah, but they are also not about Sarah. They are about a growing tide of anger and concern over pitiful rape conviction rates, about the paltry numbers of sexual crimes that actually reach court. They are about increased violence against women during lockdown, and a growing sense that things are going backwards instead of forwards. They are about Everywoman.

As one young women told a news broadcast: “It could have been me; it could have been any one of us.”

Stranger murder is relatively rare. Femicide is not. The story of Amy Stringfellow, killed by an ex-partner who branded his initials into her arm, was published on the inside of papers that carried Sarah’s picture on the front. And the truth is, Amy represents the prevalent problem, the largely ignored one – a woman is killed by a male partner every three days in Britain. Our homes are not safe havens any more than our streets.

Walking home. It carries such connotations of warmth and safety. Out running in sunshine this week, I felt, like many people, a sudden surge of sadness for Sarah Everard, and an anger that she would not see a vibrant field of yellow and blue crocuses like the one I passed.

She should have been safe. She should have made it home. And she should have been safe when she got there. Sarah… Amy… all of us.