A friend made my day recently. “That song of yours,” he said (I’m in an unpopular beat combo called Fat Cops), “I really like the line ‘I’m a man with a thirst, a thirst on my conscience’. That’s pretty deep, man.”

I was thrilled because a) it’s really cool when someone quotes your own words back at you, and b) that’s not the actual lyric. The line in our song Drink All the Drink (I’m afraid we’re that kind of band) is considerably more prosaic: ‘I’m a man with a thirst, a thirst that needs quenching’.

More than releasing a record, or playing live shows, or hearing yourself on the radio, or getting reviewed in the music press, this was the moment I knew we’d arrived: we had our very own mondegreen.

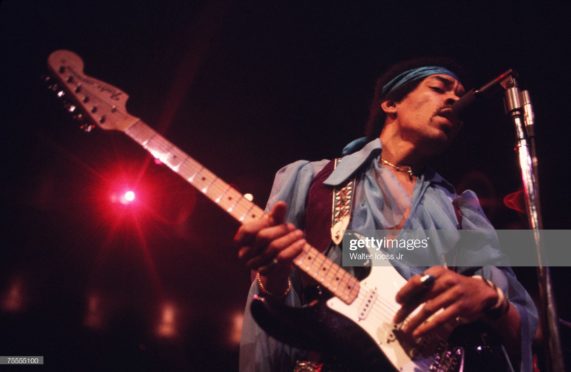

A mondegreen, if you don’t know, is a misheard phrase in the lyrics of a song. We all have them – we all belt them out with absolute commitment in the kitchen when a particular tune comes on the radio. There are the classics, such as ‘scuse me while I kiss this guy’, instead of ‘scuse me while I kiss the sky’ from Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze, which Hendrix liked so much he started singing it live – a fairly radical piece of audience participation.

Then there’s ‘spare him his life from these warm sausages’ from Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, or ‘hold me closer, Tony Danza’ from Elton John’s Tiny Dancer, or Abba’s ‘see that girl, watch her scream, kicking the dancing queen.’

Some are simply very funny, like The Police’s So Lonely being misheard as ‘Sue Lawley’ – ‘It was played on national television as an homage to Sue, but we didn’t complain. Blessings are often unexpected,’ Sting has recalled.

Or there’s the famously indecipherable line ‘call me when you try to wake her up’ in REM’s The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonight, taken by some as ‘watching Cheryl Baker hug’.

The very word mondegreen is a mondegreen, with, pleasingly, a link to the Press and Journal community. It stems from a 1954 essay in Harper’s Magazine, in which the American writer Sylvia Wright described how, as a young girl, she misheard a line from the 17th-century Scottish ballad The Bonnie Earl o’ Moray.

To her, the song went like this: ‘Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands / Oh, where hae ye been? / They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray, / And Lady Mondegreen.’ The final line is in fact ‘And laid him on the green’.

Wright wrote: ‘The point about what I shall hereafter call mondegreens, since no one else has thought up a word for them, is that they are better than the original.’

This, I would argue, is true. I asked the good people of Twitter yesterday for their favourite examples, and among the usual lines mentioned above came some fresh crackers.

‘A friend’s mum banned them from listening to Billy Ocean singing “go and get stuffed”’, said one correspondent, referring to the song When the Going Gets Tough. Another reported that KD Lang’s Constant Craving had always been ‘can’t stand gravy’ in her household. Yet another recalled a work colleague who thought the opening line to Brian Adams’s Summer of 69, ‘I got my first real six-string’, was ‘I got my first real sex dream’, which sounds like a different kind of song entirely. Someone’s brother insisted David Bowie sang ‘this is ground control, tomato Tom’, rhyming tomato with potato.

There is a simple joy in this – it brings to mind the fresh, innocent air of youth. We can all remember rushing home with a new album by a favourite artist and crowding round the speaker with friends in an attempt to decipher the words of wisdom emerging from the vinyl grooves. We’ve all had teenage arguments with said friends about what exactly those words are, the precise wording mattering a great deal – more than life itself! – to us.

We’ve all imagined that the words to a particular song speak directly to us, could in fact have been written for us. The poetry and flow of lyrics has accompanied us through the exciting early days of new relationships, comforted us through break-ups, nursed us through loss and provided catharsis in moments of stress. It’s easy to forget in those moments that most of those ‘meaningful’ words will have been hastily scribbled on a tatty piece of paper by a snotty-nosed kid with no girlfriend and zero life experience, as the lead guitarist demands he hurries up and asks why he couldn’t have done this last night at home.

But that, in the end, is the beauty of music. The spirit matters more than the reality. Our personal interpretation is what counts, rather than whichever dramatic life incident or po-faced sentiment or pressing need inspired the songwriter.

Indeed, many of the most inspiriting and life-affirming lyrics are the simplest, those that are impossible to mis-decipher – ‘should I stay or should I go?’, ‘standing on the beaches looking at the peaches’, ‘I wanna hold her, wanna hold her tight / Get teenage kicks right through the night.’ Marvellous.

So which is better, ‘a thirst on my conscience’ or ‘a thirst that needs quenching’? When Fat Cops support the Happy Mondays in Aberdeen and Inverness in October, I might just do a Hendrix.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland