Before I give you the answer, take a stab at guessing the age of each member of the Travelling Wilburys when the band released its first album in 1988.

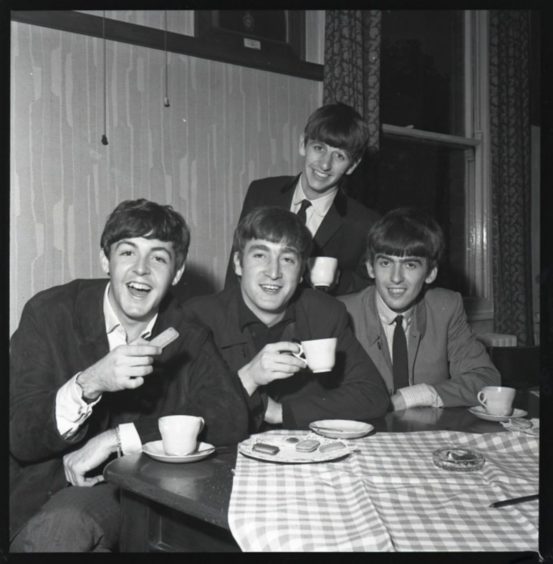

The Wilburys weren’t so much a supergroup as a superdupergroup – Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Roy Orbison, Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty.

They were the musical equivalent of this season’s Paris St Germain frontline, as if some gamer geek had discovered a rock ‘n’ roll cheat code. All that was missing was a Rolling Stone.

Unless you’ve looked it up, you’ll probably be surprised at just how young they were. Dylan was 47, Harrison 45, Lynne 41. Petty, at 37, could still have been playing for PSG.

At 52, Orbison was the eldest by five years and the only one older than I am now. I’m sure it depended on your age at the time, but back then they seemed quasi-geriatric to me. In truth, they were barely middle-aged.

The band’s superannuated feel stemmed in part from all that they had previously and individually achieved in their tender years. Orbison’s solo career had effectively been over by 1965, by which point he’d had top 10 hits with Only the Lonely, Crying and Oh, Pretty Woman.

Lynne’s ELO were a 70s thing, a decade in which they delivered an extraordinary run of pop classics. Dylan was Dylan and Harrison… well, Harrison had been an actual Beatle. Petty, the only one still in the full flush of his career, must have spent as much time rubbing his eyes as picking at his guitar.

Only Dylan and Lynne are still with us today, and we must come to terms with the reality that we are on borrowed time with popular music’s finest generation of piratical pioneers.

The greats that remain

The sad and unexpected passing last week of Charlie Watts at 80 has struck a foundational blow to the Stones, who have often given the impression of immortality. There’s a good climate change joke that asks youngsters to think about what kind of world they’ll leave behind for Keith Richards.

News of Watts’s death came just as I had begun watching a new six-part documentary series called McCartney 3,2,1.

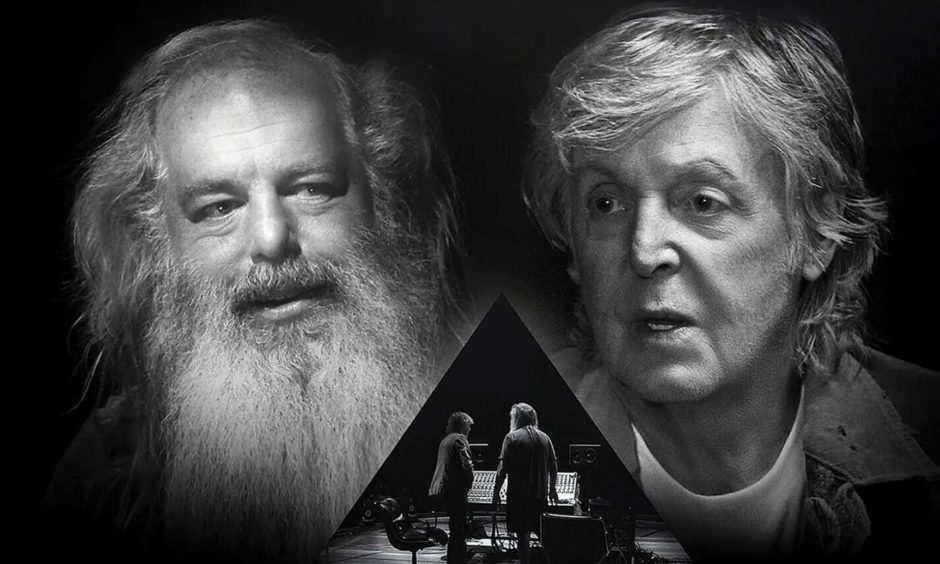

It’s a curiously low-key yet deeply affecting and treasurable thing: Paul lounging in a studio with the venerable record producer Rick Rubin, shooting the breeze about his time in the Beatles, his solo career, and his approach to songwriting.

Rubin, lavishly bearded and in shorts and bare feet, spends much of the programme literally sitting at McCartney’s feet as the 79-year-old legend natters away. One of them occasionally leans over a mixing desk to nudge up a particularly acute harmony or innovative bass or guitar track.

It’s an unusually charming and captivating format, and at one point I realised I had a broad smile on my face. McCartney is so unaffected, so typical in his enthusiasms and mannerisms of so many lesser musicians I know, that he makes his genius seem almost commonplace.

There’s nothing ordinary about the music, of course, though there is a very funny moment where he goes to the piano to play Rubin a work-in-progress.

He stares intently at the producer while he plonks away at what can only be described as a bog-standard melody. Rubin can only shake his head in slightly-forced awe and repeat “it’s amazing” and “it’s so beautiful.”

If you’ve ever been in a band you’ll recognise the experience.

Preparing for winter…

Good as it is, 3,2,1 is merely a taster for one of the big musical events of the year – in November, Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson releases Get Back, a three-part, six-hour documentary covering the 1970 recording of the Beatles’ Let it Be album.

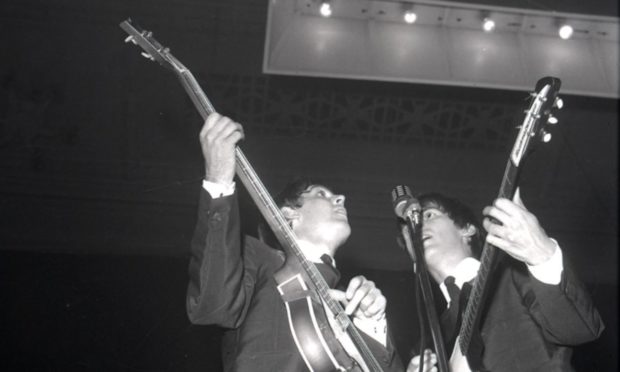

The making of the record is generally held to have split the band up, as simmering tensions surfaced between McCartney and John Lennon, Harrison became disillusioned at the restrictions placed on his songwriting by the Fab Two, and the growing influence and presence of Yoko Ono curdled relationships.

The film is expected to show the sessions in a different light, with the group larking around and enjoying each others’ company.

Ringo Starr describes it as “hours and hours of us just laughing and playing music… there was a lot of joy.”

As the months and years pass, the herd of true greats will thin further – if anything, the scale and pace of loss is likely to accelerate.

It feels important therefore that we give them our time, our ears and our heartfelt appreciation while they are still around to reminisce and explain and to share the joy.

They are living history, composers of the soundtrack to our laughter and tears, our love and loss. They are the most sublime inventors of our world, and we will miss them terribly when they’re gone.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland