I enjoyed a sweet moment spectating from the sidelines as a ball flew across the pitch and was smashed into the back of the net.

It’s why they call it the beautiful game, even although I was only watching a bunch

of five-year-olds.

It was magic nonetheless, especially as one of my grandsons scored the goal, but far from the glamour of the Euros.

I’d made a flying visit to a kids’ football camp in Aberdeen, but it set me thinking about a sadder part of the sport which destroys family life.

His coach provided the “cross” and it didn’t matter that the ball was rolled by hand for my grandson to shoot. He was learning a skill even professionals mess up with depressing regularity.

We didn’t know about the potential for brain damage

I was proud, just as I was all those years ago when my son – his dad, of course – headed a goal in a school match. The ball was hit hard from a corner and my son’s head – yes, my son everyone – thudded it into the net.

The memory is as bright as an electronic scoreboard at a football stadium. And I pray it stays where I can see it, even if my brain starts falling to pieces in old age.

It never crossed my mind that others might end up dead by heading a ball day in, day out for a living.

Now the football world – and parents – are much more aware of potential brain damage. Rules have tightened to demand softer footballs for children, and restrictions over heading practice at schools and training camps.

Possible link to dementia demands caution

At home we threw a soft foam ball for my son to practice headers. The odd thing was that I bought a couple of kids’ footballs from a toy shop the other day and they were as hard as rocks. Just kicking them was uncomfortable – heading one could be painful.

The jury might be out in some quarters about how conclusive the link is between heading injuries and dementia, but there is a mass of evidence to justify caution.

Only a few weeks ago concerns emerged about female footballers being more at risk from concussion when heading the ball.

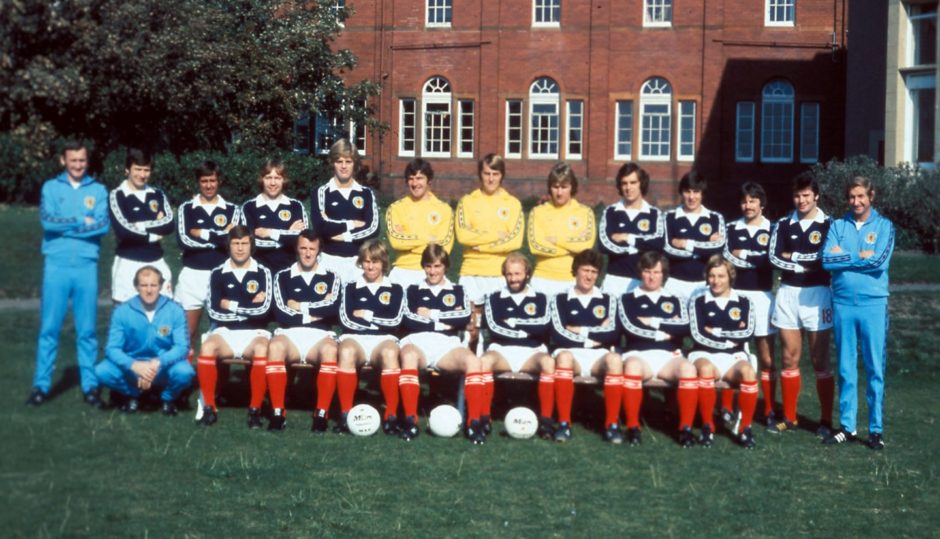

Up to now it has been famous old male pros – forgotten, ignored and fading away with dementia – in the headlines. In Scotland, past international stars Gordon McQueen and the late Billy McNeill spring to mind.

Footballers with lasting injuries need financial support

The Scottish Government is under pressure to class players living with football disabilities as suffering industrial injuries, opening the door to greater financial support.

Their suffering is no different from any other trade where the scale of life-threatening hazards only emerged in later life and legislation was forced to catch up. It saved others following in their tragic steps.

Scotland is among smaller countries bidding for glory in the Euros, just as Ireland (under manager Jack Charlton) famously did 30 years ago.

The former England star died while suffering dementia last year, but I watched a moving documentary recently about his amazing life and final days – Finding Jack Charlton.

Colourful memories engulfed by a black void

The narrator explained that professionals from Jack’s playing era were five times more at risk from brain damage. Incessant heading probably caused the damage, along with the ridiculously heavy footballs of the time – especially when sodden by rain.

The saddest scenes in the documentary came when Jack Charlton’s wife asked him what it was like to be idolised as a national hero in Ireland.

All he could say was: ‘I have no idea.’

I dodged this problem at school. I just ducked. I never got over the shock of heading a big heavy wet ball incorrectly on one shuddering occasion.

Excruciating pain as it smashing into the sensitive top of my skull, rather than my forehead, makes me wonder if my tender young brain was wobbling around like a boxer’s after a punch.

The saddest scenes in the documentary came when Jack’s wife asked him what it was like to be idolised as a national hero in Ireland.

All he could say was: “I have no idea.”

Colourful, gripping memories were engulfed by a black void as his brain deteriorated.

Is aggression encouraged in football?

I am not being a killjoy, by the way; I enjoy the excitement and bravery as much as anyone else.

At football camp I was distracted by other boys of nine or 10 playing on an adjacent pitch. They were showing more aggression than the five-year-olds.

A burly centre-half had just suffered the ignominy of having rings run around him by a smaller chap. Shortly afterwards, no one except me spotted the bigger boy creep up and kick his skilful opponent as a warning not to try the fancy stuff again.

That sort of hardman behaviour might take him to the Euros one day.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of the Press & Journal