In a ruined kirkyard on the edge of Stonehaven, a pink granite obelisk stands out among a jumble of greying ancient headstones.

Its inscription reads: ‘Erected by a few friends in memory of George McCondach, who lost life in the New Mains of Urie tragedy 16th May 1893, aged 22 years’.

Behind those simple words lie a compelling story of a farm worker tormented and bullied to breaking point – leading to a chilling murder in the bothy.

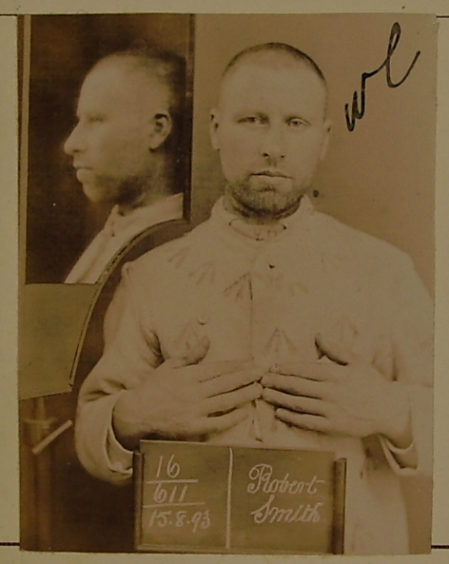

Cattleman Robert Smith was the man who pulled the trigger of a shotgun aimed at McCondach’s head, snapping after months of being subjected to almost daily name-calling and taunts.

The killing shocked the country, the trial gripped the nation.

But it was Dr Matthew Hay – the founder of the Granite City’s Foresterhill hospital complex – who saved Smith from the noose, by persuading a jury he had been provoked beyond reason and was of unsound mind when he loosed both barrels.

The story, a cause celebre 127 years ago, might have been lost in time.

But Dr Keith Stewart, a keen local historian and former vice-chairman of the Stonehaven Heritage Society took an interest in the unassuming granite marker in St Ciarian’s Kirkyard, next to his home in Kirkton of Fetteresso.

Dr Stewart, a retired clinical scientist at Aberdeen University, was originally told a different version of events.

“I asked one of the well-known local historians of the time what the memorial was,” said Dr Stewart.

“He said it was a prank gone wrong.

“This George McCondach was in the bothy, his friends tied him up in front of the fire and he effectively roasted to death, which is completely different to what actually happened.

“I think that’s what the historian’s GP father had told him because he didn’t want to get into this thing about murder.”

The truth was complex and tragic

The truth, though, was more complex and more tragic, as Dr Stewart discovered in 2016 when he was carrying out research on those buried in St Ciaran’s Kirkyard and made contact with a fellow medic, genealogist and author, Dr John Burt.

“It turned out he had just written a draft version of the story of George McCondach and told me this was in fact a murder on New Mains of Urie,” said Dr Stewart, who went on to research the story further with Dr Burt and co-author Kathryn Burtinshaw.

Robert Smith was a cattleman, born in Laurencekirk, who had worked on various farms around Stonehaven before working at New Mains Of Urie, at the bottom of the steep Netherley Road on the track into the town, in October 1890.

“He was a well-known cattleman and very well-respected and knowledgeable,” said Dr Stewart.

But soon after he started, Smith became the butt of jokes and jibes by three of the unmarried farmhands who lived in the bothy adjacent to the cottage he shared with his wife, Jessie, and their three sons and daughter.

The bothy loons – McCondach, William Robertson, who was 16, and farm servant Thomas Mitchell – would boo and jeer Smith when they saw him, laugh at him and call him names, like “bullhead” and “cow-killer”.

At one point they blocked his cottage chimney, filling the house with smoke and smeared cow dung on the handles of his wheelbarrow.

They took delight in tormenting him.

Dr Stewart said: “They were effectively jeering Robert Smith every day in life, to the point where he actually went to the farmer and said he wanted out of the contract.

“Because he was such a good cattleman, the farmer refused.

“Robert Smith also went to the local police and said: ‘These guys are making my life hell’ and nothing was done.

The bothy loons were shouting names

“What happened on the 16th of May 1893 was he had been up all night looking after a sick cow,” he said.

“In the early hours of the morning, the bothy loons are there shouting names after him and the rest of it.

“The loons see to their own work and go back in to the bothy to make their breakfast.

“At about 5.30am, another of the bothy loons, Charlie Gordon, sees Robert Smith coming up from the steading with two shotguns.

“He goes straight into the bothy and says to this chap: ‘Get out, I’ve nothing against you’, and just shoots George McCondach in the head, killing him.

He just shoots

George McCondach

in the head, killing him.”

“He’s about to shoot William Robertson, but he manages to get out the back of the bothy and runs towards to the next houses to get help, but he was shot in the shoulder, severely injured but not killed.

“Then Robert Smith just walks out the farm, he meets the farmer and hands him the guns and says: ‘I shot two of your men today, I can die happy – I shot them down like hares’.

“That sounds like a cold-blooded killer.”

The police later found Smith hiding in Cowie Kirkyard but he went with them quietly to be held in Craiginches Prison before his trial.

On Wednesday July 5 1893, the Aberdeen Press and Journal reported the start of proceedings against Smith had caused “great interest to be manifested” with a rush for places and before 10am the courtroom was full, with police and the Gordon Highlanders guarding the door.

On Smith’s arrival at the court in a police cab, a crowd gathered on Castle Street rushed to catch a glimpse of the accused.

The report said: “Smith, with a careless air, stepped to the pavement.

“He was handcuffed and (police) officers proceeded to lead him by the arms.”

In the course of the trial before Lord McLaren and jury, a picture emerged of the relentless taunting and bullying Smith had endured.

But doctors and medical experts of the day argued Smith was not insane when he pulled the trigger – all except Dr Matthew Hay.

Smith was unbalanced due to provocation

He was Medical Officer of Health for the City of Aberdeen and professor of medical jurisprudence (the forerunner of forensic medicine) at Aberdeen University.

Dr Stewart said: “He took the time to go and see Robert Smith when he was awaiting trial in Craiginches.

“He quickly came to the opinion that Smith was unbalanced because of this extreme reaction to provocation.

“He was insane when he took that gun and shot the guy in the head.

“The jury came to the conclusion it wasn’t murder but culpable homicide because of provocation.

“Had they not believed Matthew Hay and put him to prison, this guy would have been strung up.”

The verdict raised some eyebrows at the time.

The Aberdeen Evening Express described Smith as being “mercifully dealt with”.

It went on to say: “In forming an opinion on the verdict in this case, one cannot help feeling that as a punishment there is precious little to choose between the capital sentence and penal servitude for life.

“The one is speedy, the other is living death”.

One is speedy,

the other is a

living death.”

As it turned out, Smith was to live until 1937 when he died in Montrose Royal Asylum aged 75.

Initially, he had been sentenced to life in Peterhead Prison, sewing mailbags and breaking stones in the quarry.

He was transferred to Perth Prison in 1906 where there was a specialist mental health unit as it became clear he was suffering acute paranoia and delusions of persecution, accompanied by incoherent range.

Dr Hay was proved correct

“Ultimately, Dr Matthew Hay was proved correct,” said Dr Stewart, who has given many talks and presentations on the fascinating story.

The story is also featured in a book by Dr Burt and co-author Ms Burtinshaw called ‘Madness, Murder and Mayhem: Criminal Insanity in Victorian & Edwardian Britain’.

And earlier this year the trial was recreated as part of Aberdeen’s Granite Noir crime writing festival.

In 1922, suffering from dementia and no longer a threat, Smith was transferred to Montrose Royal Asylum.

His death, 15 years later, went unremarked and unmourned – his wife had disowned the sons she had with him and remarried.

The boys ended up being sent to a home then on to Canada as farm workers.

Smith’s daughter, Agnes, stayed with her mother but years later emigrated to Canada.

Robert Smith, the mild-mannered, law-abiding man who snapped at the hands of bullies and committed bloody murder in a bothy, would be all but forgotten today, save for a pink granite marker in a tumbledown kirkyard.

Tragedy in the words of a wife

Central to the tragic story of Robert Smith was his wife Jessie.

On May 19 1893, the Aberdeen Press and Journal carried an interview with her about the tragedy.

She spoke of her husband as a kind husband and father who was devoted to his work and always had a “quiet temperament”.

But she said her husband felt the torment of the McCondach, Robertson and Mitchell “very keenly”.

On the morning of the killing, he had returned to their cottage at 5.30am after attending to the cattle.

I saw there was

something wrong …

there was a queer

look on his face.”

Mrs Smith said: “I saw there was something wrong.

“There was a queer look in his face.

“His mind seemed to be unhinged but yet he spoke quite calmly.

“He went to the window and took down his gun and then coming back to me he told me what had taken place since he had gone out.

“The three men, he said, had been making a fool of him again.

“He then loaded the gun and went out.

“As he crossed the doorstep, he said: ‘It’ll be nae warnin’ tae them, but it’ll be a warnin’ tae ithers’.”

She said he bade the children and herself goodbye and told her what to do with some of his things before walking out the door.

A few minutes later Mrs Smith heard the report of a gun.

‘Murder in my living room’

The New Mains of Urie tragedy may be forgotten by most but not by Colin Sim.

“That murder happened in my living room,” said Colin, who lives in the converted bothy and cottage where the bloody and tragic events of 1893 played out.

New Mains of Urie is today a pleasant row of three cottages, sitting along a farm road, at the bottom of the main Netherly Road into Stonehaven.

Once it would have been on the main road into the town, running past the long-vanished distillery.

Now a cul-de-sac, on one side sits the new houses of the Urie Estate.

The traffic from the nearby junction of the AWPR and A92 forms a faint backdrop of sound.

Colin, a telecoms engineer and his wife, Linda, moved into the house in 1992, but it wasn’t until some years later they discovered its grim past in the most unexpected way.

“In April 2010 Linda was at home recovering from a broken elbow because she had fallen of her bike,” he said.

Mind you, it’s

always cold in

that room.”

“There was a knock at the door and a man said: ‘I hope you don’t mind me knocking on the door, but did you realise there was a murder in this house? I’m doing some research on it’.

“That was the first we had heard of it.”

The couple never found out who the man was.

“Linda just gave him short-shrift and closed the door,” he said.

Colin asked locals more about it and found out the grim story.

“It didn’t faze us,” he said, laughing at the question of whether he had any spooks in the house.

“No… mind you it’s always cold in that room.

“That might have something to do with it.

“But it is quite a story to tell in the pub.”

Colin thinks the case of Robert Smith, bullied to the point of snapping, is both sad and relevant to today.

“Bullying still happens and you can see how people resort to things like that.

“I don’t think anyone being bullied is nice.

“With all the anti-bullying stuff we see, it does still resonate today,” he said.