The Scots language is still proudly spoken by hundreds of thousands of people across the north of Scotland.

Yet, as a new television programme reveals, its survival and recent development has happened in spite of efforts by teachers and other administrators to ban a language which they regarded as proof of a poor upbringing and an anachronism.

Until the 18th century, it was commonly taken for granted that Scots was a language, but it was gradually demoted from ‘national’ to ‘provincial’ status, people became focused on their local dialects and alternative and regional names began to emerge.

The most prominent of these was ‘Doric’, as coined by the poet Allan Ramsay in 1721. He used the term with affection, and it was often understood to mean simple, ‘pure’, plain-speaking, but people coming after him often criticised what they perceived as an old-fashioned language and the stage was set for conflict.

In contrast to regions such as Lanarkshire, where industrialisation was significant, the counties of Kincardine, Aberdeen, Banff and Moray remained very rural and so retained a strong sense of continuity and tradition. But this cut both ways.

Gradually, during the 20th century, the use of Doric fell out of fashion in many places which experienced strong industrial growth and Anglicisation. And that has sparked a culture clash which has often proved divisive.

Campaign of vilification

For years, Scotland’s ancient tongue was ignored or mocked. Those who used it at school often found themselves being belted for employing resonant, evocative words which they had learned from their parents and grandparents before them.

The campaign of vilification reached the stage where a 1946 report on primary education argued that Scots “is not the language of ‘educated’ people anywhere, and could not be described as a suitable medium for education or culture”.

The same study called for teachers to wage an “unrelenting campaign” against Scots and many youngsters were frightened to stand up to their elders.

However, as part of the documentary which will be aired on BBC Scotland on Tuesday at 10pm, Alistair Heather travelled the length and breadth of the country to discover how the language was faring in the 21st century.

Loons and quines

His findings indicate that the colourful and descriptive words which were beautifully used by writers such as Lewis Grassic Gibbon in Sunset Song have been maintained, adapted and expanded by a younger generation of loons and quines.

Mr Heather said: “The project was developed over six months or so, during which time I was working at Aberdeen University on their Scots language initiatives, and writing the film in my spare time.

“It was developed initially with Nadine Lee at BBC Beechgrove and the Aberdeen office were central to the whole production. This was helpful as it ensured that everyone involved at the start had a good ear for and an affinity with Doric Scots.

“We travelled across the mainland, exploring the different dialects of Scots in Buckie, Peterhead, Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Hawick and Glasgow.

“It is a very human story, focusing on the experiences of their language that people in different areas have had. We also went to the National Library to look at the Scots publications over the years that have led us to where we are today with the language.

“In the 1500s, you had Scotland’s first published medical text being printed in Scots: a pamphlet giving people medical advice on how to spot if they are infected with the plague, and what they can do to protect themselves. It has some resonance today!

“We also found an example of official suppression of the Scots language in the north-east, with the 1946 report on primary education.

“But we have seen how Scots has survived despite these attacks from the education system and the BBC.

“We all know the richness and diversity of Doric Scots and that really comes across in the film. Different generations of speakers from different backgrounds show that the language is still the Mither Tongue – though it remains under threat.

“The biggest surprise for me was the Scots dialect of Hawick.

“It is incredibly similar to north-east Scots in many ways. For example I heard folk say: ‘Div ye ken at mannie? Aye A div’ – I had always thought ‘div’ was just north east.

“But it’s because both Hawick and the north east are further away from Glasgow and Edinburgh, they have retained more of the traditional vocabulary of Scots.

“In Hawick, as in many north-east towns, Scots is the first-language in shops, in the playground, on the sports fields. We visited the school, where the English teacher, born south of the border, teaches Scots to her pupils.

“I learned that, at a grassroots level, people are taking more pride in their language and using it with more confidence in public spaces.

“But it’s still crying out for political support, and needs wider use in the media.”

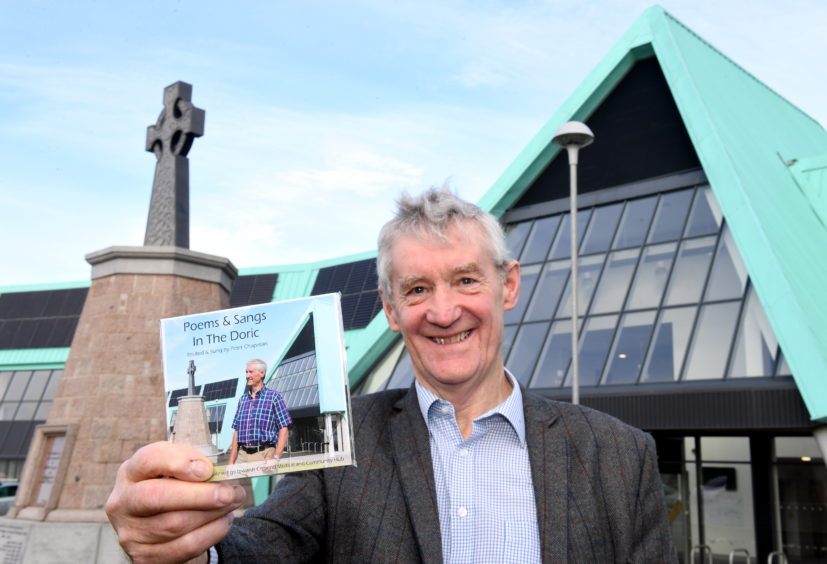

Fundraising album

Scottish Conservative MSP Peter Chapman has raised around £3,500 from his Doric CD, with the money raised from the sales of his album, poems and songs going to the Crimond Medical and Community Hub.

Yet he realises there is no room for complacency in ensuring the language continues to be spoken in an age where more and more people employ Americanisms.

A few years ago, @gabiReith and I did an affa rare project to find Aberdeen’s favourite 100 Doric words for @CLT_Abdn and here they are grouped together by similarity. Bosie was the #1 favourite! pic.twitter.com/MPj4yerJ7r

— Shane Strachan (@Shane_Strachan) April 21, 2020

The politician said: “The programme is about celebrating the Doric and the importance of keeping the language alive.

“Doric is part of our culture, forms our heritage and makes the north-east a unique place to come and visit.

“I have spoken Doric all of my life and it’s vital we keep it going which is why I was delighted to take part in the programme to raise awareness of the language.

“It was fantastic to grow up with the Scots language and I want to ensure that Doric remains present for generations to come.

“As generations pass and come through, we’re losing a larger chunk of something which provides us with significant importance to the history of the area we live in.”

Champions of the Scots language are cautiously optimistic about the future. But they know much work remains to be done as language evolves and develops.