It is 75 years since the men who sailed on the Arctic convoys were finally offered a respite from embarking on a “mission to hell”.

Even Winston Churchill described their experiences as the “worst journey on earth” and thousands of serving personnel perished in sub-zero conditions as they strove to keep the naval routes open, while resisting their German adversaries.

Battle to preserve crucial routes

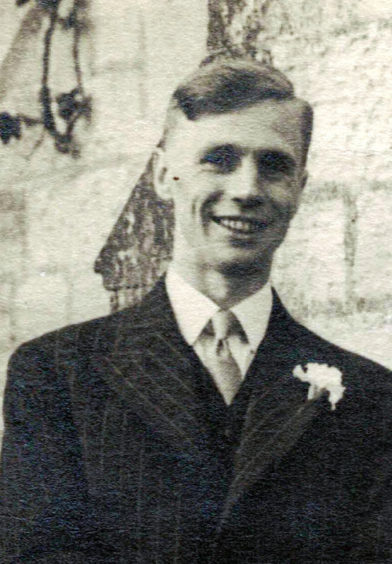

Sub-Lieutenant John Boothroyd was among those who braved the elements and the enemy, repeatedly sailing into treacherous, storm-battered territory after leaving Loch Ewe in the Highlands and Scapa Flow on Orkney.

He never forgot the stomach-churning privations which he and his comrades encountered as they battled to preserve crucial routes for the Allies.

The old campaigner died in Melbourne, Australia, in 2007, but his daughter, Alison Hutchison has now told her father’s remarkable story – one which eventually led to his family receiving the Arctic Star medal, but only more than a decade after Mr Boothroyd had passed away.

Yet, even if his exploits were in danger of being overlooked, Mrs Hutchison has revealed the sense of joy and relief with which Mr Boothroyd and his colleagues reacted to returning to Scotland on VE Day on May 8 in 1945.

She said: “Before dad died, he was in a nursing home in Sunbury and, one day, while I was there, a social worker came to do an assessment of his memory.

“Part way through, the following exchange took place: ‘John, where were you and what were you doing on VE Day?’

“John pulled himself up in his chair as if he needed a straight back to reply.

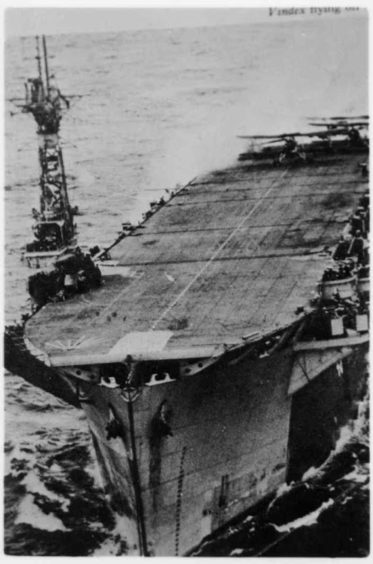

“Then he answered promptly and proudly: ‘I was standing on the deck of HMS Vindex as it steamed up the Firth of Clyde at the end of an Arctic Convoy. The whole crew was standing in formation on the deck of the aircraft carrier as it came into dock at the Tail ‘o the Bank. And there was a huge party that night’.

“On VE Day, John had completed his eighth Arctic convoy – which saw him returning from the Kola Peninsula.

“It was the last Russian Arctic Convoy which was undertaken during wartime (RA66).

“HMS Vindex was an aircraft carrier and my father served as a radio and radar officer with the Fleet Air Arm Squadron 813.”

No more horrific hurricanes

Mrs Hutchison added: “When he answered the question, 60 years after the event, I could still sense the relief in his voice, describing that moment – he was just 21 years of age, standing with the whole crew on the deck of the aircraft carrier knowing that there would be no more convoy voyages for him.

“That meant there would be no more horrific hurricanes in icy waters, ice-clogged equipment, U-boat attacks and Luftwaffe threats.

“Nor any more technical support for Swordfish aircraft pilots and observers in their freezing, open cockpits, which set out but, on occasion, never returned.

“Two years ago, I received from the British Government John’s Arctic Star medal.

“It was greatly appreciated by his family despite the decades of delay.

Mr Boothroyd willingly accepted every challenge which was aimed in his direction and the Arctic Convoy museum at Aultbea in the Highlands has painstakingly gathered the recollections of men in his mould who risked their lives whenever they left Britain.

They chronicle the often appalling circumstances in which the convoys travelled and Mrs Hutchison highlighted one particularly traumatic incident which happened just three months before the cessation of hostilities in Europe.

Worst Arctic journey

She said: “John’s worst Arctic journey was in February 1945 – Convoy RA64 – on the aircraft carrier HMS Campania.

“John was on deck and watched as a corvette, HMS Bluebell, was sunk by a torpedo from U711.

“The ship sank in 30 seconds with over 80 men lost.

“There was only one survivor.

“As John said, to see the ship there one minute and gone the next was an extraordinary experience.

“The conditions weathered by RA64 in February 1945 were reported to be the worst endured in the entire North Atlantic theatre.

“The convoy was hit by two hurricanes.

“HMS Campania rolled 45 degrees each way and equipment and men were flung in all directions.

“There was concern about leaking fuel from motors and other equipment that had been upended.

“It was a harrowing experience.”

He wrote the following about the storm (on the back of a photograph of HMS Campania): “The waves in the worst storm of the war, in February 45, were twice the height of the flight deck – hence they were 60 foot high.

“I decided that when people like the senior engineer looked worried, it was time for me to be worried.

“The 45 degree roll each way was very slow.

“Crossing the ship below decks, one hung on and when level, the instruction was: ‘run like hell and hang on again’.”

Mrs Hutchison said official records later confirmed that the HMS Campania rolled one way and 45 degrees the other way.

She said she wanted people to be aware of the sacrifices which had been made by so many young men three quarters of a century ago.

Especially since their myriad acts of valour have often been forgotten.

John Boothroyd’s service in the Convoys

Mr Boothroyd described his role with Fleet Air Arm 813 Squadron as being a radar mechanic and observer with responsibility for maintaining radar equipment and radio communications for the Swordfish aircraft, which were deployed on aircraft carriers HMS Campania and HMS Vindex.

Swordfish aircraft were torpedo bombers, and were outdated even in 1939, because they were cumbersome, slow biplanes.

Nevertheless, they frequently proved effective on bombing raids.

He was involved in a number of hazardous and lethal convoy missions and was responsible for working with pilots to ensure that their aircraft radar was operational prior to take-off.

John was deeply affected by the fact that the very first airman whom he assisted with his radar, prior to take-off from HMS Campania never returned.

When asked about his Arctic Convoy experiences in late 2005 and 2006, he remembered all the convoy reference numbers immediately and some of the most significant events on every assignment.

He was on four return-trip Arctic Convoys from September 15 1944 to May 8 1945.

His first convoy (JW60) left Loch Ewe in the north-west Highlands.

It consisted of two dozen Liberty ships (American), several British tankers, a Norwegian tanker, a British freighter and a rescue ship.

All hands were lost

The naval escort consisted of the carrier HMS Campania, an anti-aircraft cruiser, about eleven British destroyers, two Canadian destroyers and a battleship HMS Rodney.

The convoy proceeded north of Bear Island and on to Kola Inlet.

Mr Boothroyd recalled a surface threat from the German battleship Tirpitz which was why the convoy was supported by the battleship HMS Rodney.

On the return trip (RA60), the German submarine u-921 sank as a result of actions by HMS Campania.

On JW62, there was again no loss of merchant ships, but, on the return trip (RA62) a U-boat sank the British destroyer HMS Cassandra.

This trip was in mid-December 1944 and Mr Boothroyd vividly recalled that Swordfish planes often missed their return landing in the intense cold and dark.

Crew members frequently perished as planes ditched into the sea.

Opposition to convoy JW64 in February 1945 was fierce and a wildcat plane from HMS Campania was shot down.

There was a strong German attack off Bear Island, amidst intense snow and poor weather.

That was followed by a u-boat raid off Kola Inlet. Two British warships and an American Liberty ship were lost.

Leaking fuel concern

The return voyage RA64 was particularly memorable. Mr Boothroyd was on deck and watched as a corvette, HMS Bluebell, was sunk by a torpedo from U-711.

The ship sank in 30 seconds with over 80 men lost.

The conditions weathered by RA64 were reported to be the worst endured in the entire North Atlantic theatre. The convoy was hit by two hurricanes.

HMS Campania rolled 45 degrees each way and equipment and men were flung in all directions.

There was concern about leaking fuel from motors and other equipment which had been upended in the tempest.

Service of remembrance postponed

A commemoration to mark the 75th anniversary of the Second World War Arctic convoys has been re-scheduled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

However, a worldwide appeal to find convoy veterans or their families will continue ahead of the event being held later this year.

More than 20 veterans, including one who lives in New Zealand, had confirmed they would take part in the event on May 16 at Loch Ewe in Wester Ross, a gathering point for many of the convoys and now the site of the Russian Arctic Convoy museum.

In addition, up to 200 families of the surviving and deceased heroes had been expected to attend, along with four Russian war veterans and a number of dignitaries.

The health and well-being of those attending is also of paramount importance as the veterans are now in their 90s, and many family members are also aged over 70.

Disappointment

The event is now scheduled to take place on September 26 at the same location.

Event coordinator John Casson, co-chairman of the Russian Arctic Convoy Project, which runs an exhibition centre at Aultbea in Wester Ross, said: “We are extremely disappointed to postpone the 75th anniversary event after so much time and effort has gone into organising the commemoration in May.

“However, circumstances mean that we have no alternative to re-arranging the event.

“We must put the health of our veterans, their families and friends at the forefront of our thinking and do everything we can to help protect them.

“In the meantime, we will continue to seek convoy veterans and their families, so we have an opportunity to thank them in person for their incredible wartime efforts at the re-scheduled event.”

The convoys played a significant role in the conflict, providing four million tons of supplies and munitions to Russia between 1941 and 1945.

Veterans or their families who are wishing to attend the event should contact John Casson at johncasson@johncasson.com