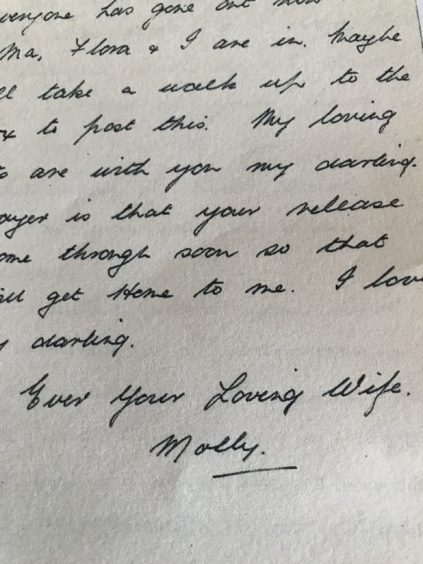

It’s a letter which sums up all the contrasting emotions of those who were married, but forced to live apart, when Britain celebrated the end of the Second World War.

There’s a heartfelt tone to the correspondence which was sent by Mary Ann (Molly) McKenzie from her family home in Aberdeen on VE Day itself – May 8 1945 – to her husband, Charlie McKenzie, a captain in the Royal Artillery, who was in charge of a group of Russian prisoners of war in Holland when the conflict drew to a close.

But her words also reveal a sense of frustration that the couple could not be together to commemorate the cessation of hostilities, allied to a tinge of apprehension lest any harm befall the man she calls her “darling” and her “sweet”.

The late couple’s daughter, Rhona Hunt, spoke about how the letter was precious in capturing the atmosphere as Aberdeen and other cities broke out the bunting and played host to a giant impromptu party which toasted the Allies’ victory.

Red, white and blue

Molly wrote about the scenes she and her family witnessed in the Granite City, both on the streets and at a church service before they went home to listen to a BBC radio broadcast by the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

She said: “The whole town has gone gay with decorations and flags.

“When we went off to church, it was grand to see all the flags fluttering and even the trams had flags on them, to say nothing of the children wearing a lot of red, white and blue.

”I have never seen so many people in Union Street.

“It was a moving mass between Market Street and the Castlegate.

“We took the tram to George Street and when we got to the church at 11, I offered my prayers and thankfulness for your safe deliverance.

”We went up to your mother’s after we came back from the church and your Ma gave me a glass of stout and impressed on me it would do no harm.

“I fair enjoyed my dinner – I just canna’ keep eating out of my letters which you will note.

”(In the afternoon) we all gathered for the Prime Minister’s speech at 3.0 (3pm) and I wondered if you were listening to it.

“It was very impressive, it MUST have been for even Ma made us all stand up in a circle and sing God Save the King.

”We had a bottle of port and we had a toast – first to Charlie, then to sister, Kay, and brother, Bill, and last to those who shall not return (from the war).

”In my heart, my darling, I have the feeling it won’t be very long before you are home. What a glorious feeling, my sweet, to know that it is really over – I can’t realise yet that it is true, the war is finished.”

The nine-page handwritten letter switches between exhilaration, relief and anxiety and Molly was pregnant at the time she wrote it – but as her daughter added: “Sadly, the baby my mum wrote about was a stillborn boy.”

Hitler on the bonfire

However, on VE Day, the mood in the family home was one of joyous positivity.

As Molly added: “I am very glad to know that you are in Holland as I would rather have you there than in Germany.

“You say your job is very interesting and one that would please (Soviet leader) Joe Stalin!

”At home, we can’t believe we don’t need to bother about the black-out (any more).

“We have built a huge bonfire at the back of the house, and lots of black boots are going into it and also a large drawing of Hitler.

“I think the general feeling here in Aberdeen is one of thankfulness.

“But it is perfectly wonderful to be even talking about what we will do when you are home.”

The couple were eventually reunited at their north-east home and enjoyed many decades of married life together, both in Scotland and England.

Mrs Hunt said: “My father was brought up in Fordyce – he was born at Glentauchers Distillery in Speyside, where his dad worked as a stillman in 1912 – but he moved to Bedford Road in Aberdeen as a young man, while my mother (who was born in 1913), was the eldest of eight girls and they lived in the city’s Ruthrie Terrace.

”Dad was a climber and a well-known swimmer – he was in the North Sea every day of the year – and Mum was a dedicated girl guide range leader.

“During the war, he became a captain in the Royal Academy and went over to France on D-Day before moving up through Holland to Hamburg in the months ahead.

“He was in charge of a group of released Russian prisoners of war during this time.

”They later moved to Spalding in Lincolnshire before eventually making their home in Derbyshire, where I live today. But they were both very proud of and very loyal to their Scottish roots throughout their lives (Molly died in 1979 and Charlie in 1991).

”My dad founded a pipe band and, eventually, a Highland Gathering here in Ashbourne and he was always much in demand to address the haggis around Burns Night.

“I spent 10 years in Laurencekirk from 2000 to 2010 when my husband lectured at Robert Gordon University and we loved living there.”

Prayer

It was a passion shared by her parents.

As her mother’s poignant VE Day letter concluded: “I am so happy, my darling. My prayer is that your release will come through soon, so that you will get home to me.

“I love you.”

Joy and sadness came together in a north-east port

The flags and bunting were out in force as Portsoy celebrated the end of the war in VE Day.

And Margaret Mair of the little village’s Barbank Street was among those who joined the party at the harbour.

However, although she did her best to enjoy the proceedings – not least because she was looking after her niece, 13-year-old Mary McConachie, it was difficult for her to hold her emotions in check as the day continued.

After all, her husband, William Mair, RNR (Royal Naval Reserve), had been killed by the Japanese during one of the most infamous episodes in the whole conflict.

Mrs McConachie’s daugher, Susan Laing, later discovered more about the incident.

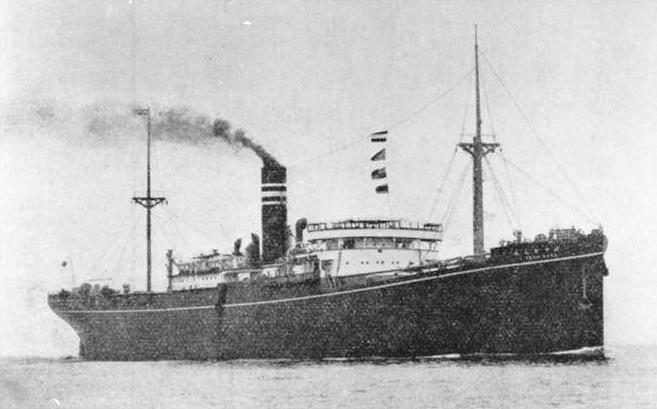

She said: “William was the skipper of a patrol vessel in Hong Kong at the time of the Japanese invasion and he was captured.

“He was one of almost 2,000 British PoWs who were aboard the Japanese freighter Lisbon Maru when it was torpedoed and sunk by an American submarine.

“Although none of the PoWs was killed by the torpedo, many were shot or left to drown by the Japanese who came to rescue the crew.

“William Mair was one of these.”

Final voyage

On what was her final voyage, Lisbon Maru had been transporting prisoners between Hong Kong and Japan when she was destroyed on October 1 1942.

It led to the loss of more than 800 lives and sparked accusations that the Japanese deliberately killed Allied troops who were in the water after the explosion.

Mrs Mair never forgot her husband – even on a day when the rest of the country was rejoicing.