It was a tale of redemption, the birth of a new South Africa, and the whole saga started on the global stage 25 years ago this month.

Some of the key players are no longer with us, including superstars in the mould of Jonah Lomu and Joost van der Westhuizen; the latter a victim of motor neurone disease, even as Scotland’s Doddie Weir continues his own gruelling battle with that awful condition.

Yet, for anybody privileged enough to have been at the 1995 Rugby World Cup – and I was there for more than five weeks and marvelled at the flowering of the Rainbow Nation – the memories will never be forgotten.

From the first few days, the pageantry was mesmerising; the juggernaut-style attacks of the one-man wrecking ball, Lomu; the cool-as-Antarctica poise of South Africa’s Joel Stransky, who kicked 22 of his side’s 27 points in their victory over reigning champions Australia in the tournament’s opening tussle; and, of course, the synergy and empathy between Springbok captain, Francois Pienaar and his country’s remarkably conciliatory president, Nelson Mandela.

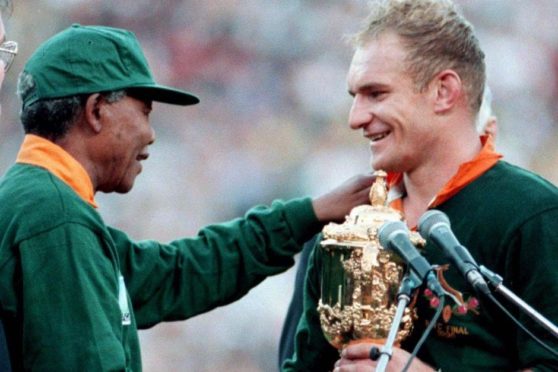

It eventually offered one of the most iconic images in sporting history when the hosts met New Zealand in the final at the imposing Ellis Park in Johannesburg; and the relationship between these two proud men offered a symbol of how sport can transform attitudes and even influence history.

And although Clint Eastwood did his best to evoke the events, both before, during and after that special day in his film Invictus, this really was one of those rare moments where you had to be there to witness it for yourself.

Because, even with the benefit of hindsight, the reality was that nothing created on a Hollywood movie stage could ever come close to recapturing the spine-tingling moment when Mandela emerged, wearing a Springbok jersey, to present the World Cup to the towering Afrikaner, Pienaar.

Those of us fortunate enough to have been present, as the Rainbow Nation united in joy while the mesmerising anthem “Shosholoza” resounded throughout the stadium, will forever cherish the sense of something special in the air.

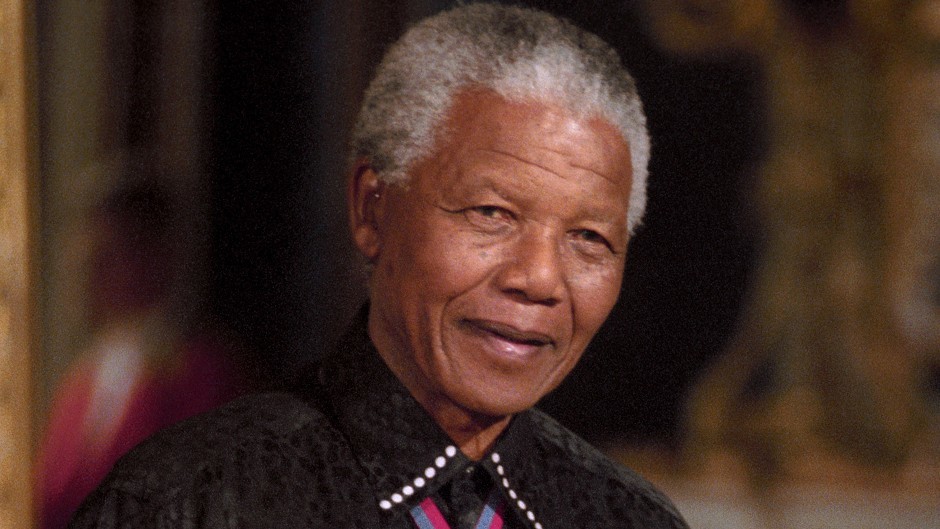

Mandela, who by then was in his late 70s, had been one of the pivotal figures in the preceding weeks of a spellbinding competition, refusing to show any bitterness towards a sport with strong links to apartheid, despite his 27 years of incarceration, 18 of them spent in a tiny cell on Robben Island. Instead, on the opening morning of the competition, the former prisoner 466/64 delivered a speech to a rapt audience in the sprawling black township of Ezakheni.

He purposefully arrived with a Springbok cap and, pointing to it, told his congregation: “This does honour to our boys. I ask you to stand by them, because they are our kind.”

Inspired by that redemptive message, the Sowetan daily newspaper subsequently carried the front page banner headline “Amobokoboko” (Zulu for “Our Springboks”) on the morning of the team’s opening fixture against the Wallabies.

They won that and, as the weeks passed, and the momentum increased, the duo forged a bond, built on mutual respect, allied to the instinctive understanding that anything which could foster racial harmony in a country still beset with tribal hostilities had to be worth promoting, and especially while South Africa was on the global stage.

On the day of the final, I travelled from Pretoria into Johannesburg in one of the taxi minibuses which had been laid on for those en route to the denouement.

“Bokke, Bokke, Bokke” was the prevailing theme, oblivious to the fact that the hosts were massive underdogs against the previously all-conquering All Blacks, who boasted the fearsome Lomu – the winger who had trampled all over England’s dreams in the semi-finals – in their ranks.

During the journey, our driver, Tembi, a middle-aged fellow with no particular penchant for rugby, spoke quietly about how he hoped the South Africans would win – and for one reason alone.

“If Mr Mandela can forgive those who locked him up, then the rest of us should try to do the same,” he said softly.

“In the old days, we used to hate rugby and we would cheer on anybody who was playing the Springboks.

“They wouldn’t allow us anywhere near their team, so why should we support them?

“But Mr Mandela has asked us to get behind these boys, so we will do as he says.”

Inside the imposing arena, prior to the kick-off, expectation mingled with apprehension and downright trepidation when a Boeing 747 flew above our heads and – for a few heart-wrenching seconds – the aeroplane seemed to be in danger of crashing right into the middle of us.

But the pilot, Laurie Kay, then repeated the manoeuvre and, this time, the crowd cheered, recognising they were involved in a special piece of pageantry.

The match itself – a protracted, nerve-strewn affair which eventually required extra time – was hardly the greatest spectacle, but the home side snuffed out the threat of the All Black backs and the tension grew.

There were no tries and the points all came from two kickers, Andrew Mehrtens and Joel Stransky, the latter of whom eventually landed the coup de grace with a sweetly-struck drop goal as his side won 15-12.

Lomu was almost anonymous and people close to the New Zealand camp made all manner of allegations in the aftermath about how the team’s food had been spiked.

But, indisputably, they froze on the grand stage and paid the price.

Once it was over, the party really commenced.

Some fans persisted in singing “Die Stem”, the old anthem which was anathema to a large number of the crowd.

But many others, including those of us who had never even heard of the song until we arrived in the Republic, belted out “Shosholoza” and awaited the presentation of the trophy.

Nobody could quite believe their eyes when they saw Mandela emerge with the Webb Ellis Cup; not even the captain himself, who had been in regular communication with the elder statesman in the previous days and weeks.

As he declared later: “Other presidents would probably have worn their best silk suit.

“But when Mr Mandela chose to wear my number six Springbok jersey – the one I had on when we beat the Australians – I knew this was a victory far more important than anything else we would ever achieve.

“It marked the coming together of a nation – the new South Africa was born on that day.”

A hush descended over Ellis Park during the meeting between these two contrasting characters; one old and ever-so-slightly frail, but imbued with an indomitable spirit; the other young, blonde and as tall as Mount Rushmore.

Then everybody burst into spectacular applause, which reverberated around the stands and carried on until we were, quite literally, all clapped out.

The friendship between the duo blossomed in the years ahead.

At the state banquet, which was held to celebrate the World Cup’s phenomenal success, Mandela introduced himself to Pienaar’s fiance, Nerine, with the words: “Would you feel offended if I came to your wedding?”

“Nerine’s jaw just hit the table,” recalled Pienaar.

“She was stunned by how incredibly humble this wonderful man was.”

On the road back to Pretoria, blacks and whites celebrated together for mile after mile on the motorway embankment. Fireworks exploded, and impromptu barbecues and beer festivals were organised wherever you looked.

It didn’t matter that it was the middle of winter in the Southern Hemisphere. Yes, the team had done their job, but this was about so much more.

As Tembi, who hadn’t gained a ticket for the final, but watched it on a portable TV in his vehicle, asked those of us in the press pack: “Did you have goosebumps when Mr Mandela walked out with the Cup?

“I know I did.”

So did the rest of us who were lucky enough to be there on that magical evening as the barbecues began.