They were men who travelled thousands of miles to fight in the Second World War.

History – and Hollywood – hasn’t made a habit of highlighting the contribution made by the myriad soldiers of Force K6 of the Indian Army in such campaigns as Dunkirk in 1940, yet there were hundreds of troops involved in one of the conflict’s pivotal campaigns and throughout the rest of the hostilities.

Talking to the sheep

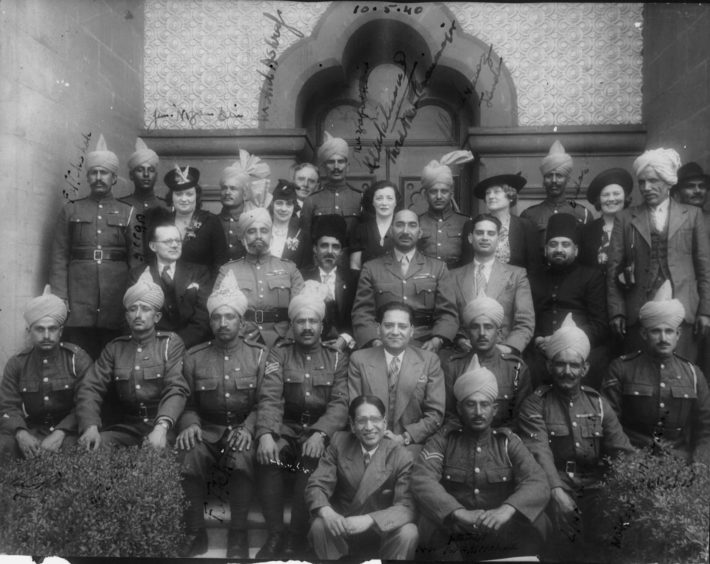

Many of these personnel were stationed at a variety of remote outposts across Scotland, from Golspie to Dornoch and Kingussie to Loch Ewe, and they gradually advanced towards the north-east in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire.

Life could be lonely.

As one soldier remarked: “When you’ve been here six months, you start talking to yourself; after twelve months you start talking to the sheep and after eighteen months, the sheep start talking to you.”

But they made friends with their neighbours, occasionally fell in love with them, were at the heart of the military manoeuvres and exercises which were held throughout the first half of the 1940s and there are poignant gravestones to some who died on Scottish soil in Highland cemeteries.

Their stories have now been chronicled in an evocative new book ‘The Indian Contingent’ by Dr Ghee Bowman, who has spent many years investigating the way in which these Asian trailblazers made a positive impact during the war.

Mr Bowman’s labours have revealed the fashion in which Force K6 brought Asian expertise to the Allied ranks when the mass evacuation began from France as Germany launched a blitzkrieg across Europe in the early stages of the war.

‘Not a horse in the force’

He said: “Dunkirk is known for small ships, for beaches, Stukas and Tommies.

“But the reality – as nearly always happens in history – is far more complex.

“Of the 338,000 men taken off the beaches and the surrounding areas, a third were French and 630 were Indian.

“These men were in France because they brought skills and expertise that was unavailable in the British Army at the time.

“The British Expeditionary Force needed animal transport – mules – to carry supplies to the front line where it was muddy or frozen or an engine would make too much noise.

“There were almost zero men with such skills – as the saying went: ‘not a horse in the force’; but there were many animal transport companies in the Royal Indian Army Service Corps and thousands of men with specialised troops available.

“These were the soldiers who joined the British forces and their skills were very important during the war.”

The author’s research unveiled many evocative stories, and he was constantly surprised at how the Indian servicemen were regarded as near celebrities during the conflict, yet were frequently airbrushed out of the picture after VE Day.

Toy soldiers

He added: “The fact is that these guys were well known in the UK during the war, but they are forgotten now.

“They marched in no less than 61 parades around the country, they were photographed and filmed multiple times and they were poster boys for India.

“They met the King and the Queen, and presented them with chapattis to take home to the princesses (including the current Queen).

“Their image was used as a model for a set of Britain’s toy soldiers, in a famous poster of Waterloo station, for an anti-racist cartoon in the Daily Mirror, and to sell soap.

“It’s very sad that the broader Indian involvement in the war seems to have been forgotten as well.

“Two and a half million men – and 11,000 women – served in the Indian armed forces and they have often called the largest volunteer army ever.

“I was surprised that the portrait of Driver Abdul Ghani (which appears on the book cover) sits in the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow, where it has been on display for 10 years.

“And yet, once again, nobody knows the story behind it.

“I was also fascinated by the story from Lairg of the old tin church that the soldiers used as a mosque, with shoes lined up outside. Was this the northernmost mosque in Scotland?”

Among their scattered postings in Scotland, one of the most far-flung locations was at Loch Ewe in Ross and Cromarty on the west coast.

Freezing, hazardous voyage

The tiny villages around the sea loch were swamped with servicemen of many nations from February 1942, when the admiralty decided to use it as a terminus for the Arctic convoys transporting tanks, raw materials and food to the Soviet ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk.

The loch filled up with merchant ships and navy escorts – so many that a person could walk a mile across the loch from vessel to vessel without getting their feet wet.

The sailors preparing for that freezing, hazardous voyage included many Indian lascars, including Aftar Miah, who was later buried in the graveyard at nearby Gairloch.

He was from Calcutta, and aged 55 when he died in 1942, while serving as a fireman on the SS City of Keelung.

Mr Bowman has recounted how the troops forged new friendships as they settled into life in Scotland.

Happy spirits

He said: “As 1942 went on, the companies spread out over a widening area that extended northwards to the Moray Firth and beyond, and eastwards to Aberdeen.

“Part of 32nd Company (of K6 Force) were posted to the Mountain and Snow Warfare Training Centre at Glenfeshie near Kingussie, where they were used as part of the training process for infantry officers.

“In October, during Ramadan, 32nd Company embarked on an epic march to their winter quarters in Golspie.

“Their officer reported that ‘all personnel were in happy spirits’.

“The going was good and message writing was practised en route and later, when they went through the centre of Inverness, they were ‘given a warm welcome’.

Further east in Aberdeen, the men and their animals made an impression on the local children.

One young man was staying with Turnbull the butcher of Broomhill Road and recalled: “When Indian troops were training at Milltimber House, he had a contract to supply them with mutton.

“I accompanied him on several deliveries and was given my first taste of curried mutton on pilau rice almost 60 years ago and I’ve enjoyed Indian food ever since.

Local fisherman William Milne was angling in the river Dee one summer evening and got cut off from the bank and was in danger of being ‘marooned for the night’.

In the belief that somebody was drowning, no fewer than 24 of the Indians rushed to his aid, as Mr Milne told the Press and Journal in 1943.

He said: “The Indians were delighted to have rendered me assistance, but seemed almost disappointed that I was not in more serious need of their help.

“I was rather wet, but was none the worse for the experience and I was very grateful for their assistance.”

By this stage, the men were ready for a change of diet, since their tastes had evolved since coming to Europe.

In September 1942, when many of them had been in Scotland for close to three years, their commander wrote a detailed letter to the War Office suggesting a new scale of rations.

Pickles, black pepper, jam and margarine were to be introduced, reflecting foodstuffs that the men had enjoyed around the country.

The menu of spices was extended to include a mix of coriander, cumin, cinnamon and cardamom.

There was an overwhelming demand for cigarettes of British manufacture – particularly Woodbine or Player’s Weights to replace the Indian Bidi cigarettes they smoked at home.

There was also a proposal that chapattis should be supplemented with English white bread, which the Daily Mirror reported was very popular and named ‘double roti’.

Further along the coast at Dornoch, home to a small cathedral and a colony of harbour seals, the reinforcement unit was stationed south of the town from June 1943 and the Indian General Hospital was based at the Dornoch Hotel.

Mr Bowman said: “As in so many other Highland settlements, they made friends.

“Alasdair Will has a picture of his uncle Leonard as a very young boy smiling while holding hands with an Indian sepoy and an older Scottish boy.

“There is a lovely photo of an unnamed Daffadar in the online history archives of Dornoch Museum.

“The picture was taken indoors, probably in the sitting room of a house.

“With his trim, greying beard and his round-rimmed spectacles, his warm smile directed at the camera and his seated pose, he looks rather avuncular, like an old school friend visiting for the weekend.

“He sits next to the family radio, with the switches in easy reach.

“Clearly this is a figure who is so well integrated in the house that he is given the seat of honour – one can imagine him sitting here every evening, drinking tea, eating shortbread and listening to the Home Service.

“He has crossed all of 7,000 miles, but he has found a home in this coastal Highland town.”

“As Dornoch was the last location for their hospital, there are two graves in the local cemetery, the last resting places for Ghulam Nabi and Naik Abdul Rakhman, who both died of TB.

“Surprisingly, there is another Indian grave between them, that of Ram Bhopal, who died in 1960. Locals remember him as a pedlar, selling clothes and fancy goods door-to-door around the Highlands and Islands before and after the war.

“He was not the only Indian in that trade; in fact there were hundreds similarly engaged. The three graves lie together outside Dornoch; reminders of a shared imperial past that came home to even the remotest British communities.”

Scottish culture

When the Indian soldiers weren’t on active duty, they absorbed different aspects of Scottish culture and the book relates the close camaraderie which was established during these festive occasions.

As Mr Bowman wrote: “Inland from Dornoch and Golspie lies K6’s northernmost posting: the village of Lairg. With its own railway station, stables for the animals and a hotel and school gym for the men to sleep in, Lairg was well suited.

“It was also a good place to find meat, with its own cattle fair, and the largest lamb sale in Europe every August selling 40,000 lambs in a single day at its peak.

“There was a suitable place to use for prayers: a corrugated tin building, previously used as the United Free Church.

“(Local woman) Joan Leed remembers hearing the call to prayer, and seeing the shoes lined up neatly outside.

“This was also an area known for its bagpipers.

“Donny Macdonald recalled that his father, who was from an old piping family, gave lessons to a sepoy.

“In due course, the BBC came and recorded the two men playing traditional Scottish airs together.

“At the end of 1942, the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) put on a special party for the sepoys and ‘a splendid and bountiful supply of eatables was available’.

“Songs, stories and dances were performed by Indians and Scots and the medical officer spoke eloquently in reply.

“Dr Fazal emphasised the strong bond that would always exist between Scotland and India as a result of the kindness and hospitality which had been shown to Indian troops by the people of the Highlands.

“The evening concluded with a rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ by an Indian bagpiper, which ‘showed more than anything else the strength of the tie that links Scotland with India’.

A week later, the honorary secretary of the Lairg WVS, Isobel Fraser – a young schoolteacher – wrote about how sad the people of the village were that 25th Company had come and gone and expressed the hope they would return again ‘for we had hoped these fine officers and men would be our guardians for the duration of the war’.

She added: “We felt like your men were very much like our people of the Highlands in many ways, and on their return to Lairg in October last, we felt they were coming home again.”

Mr Bowman said he was keen to ensure that the legacy of those who fought and died during the war is never forgotten.

He said: “Eighty years on from the Dunkirk evacuations, I think it is time to remember that the past is a foreign country – and a very diverse one.”

The Indian Contingent is published by the History Press on May 21.